Bright Dreams - Humanities Nebraska

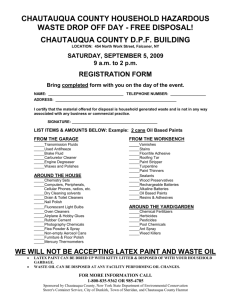

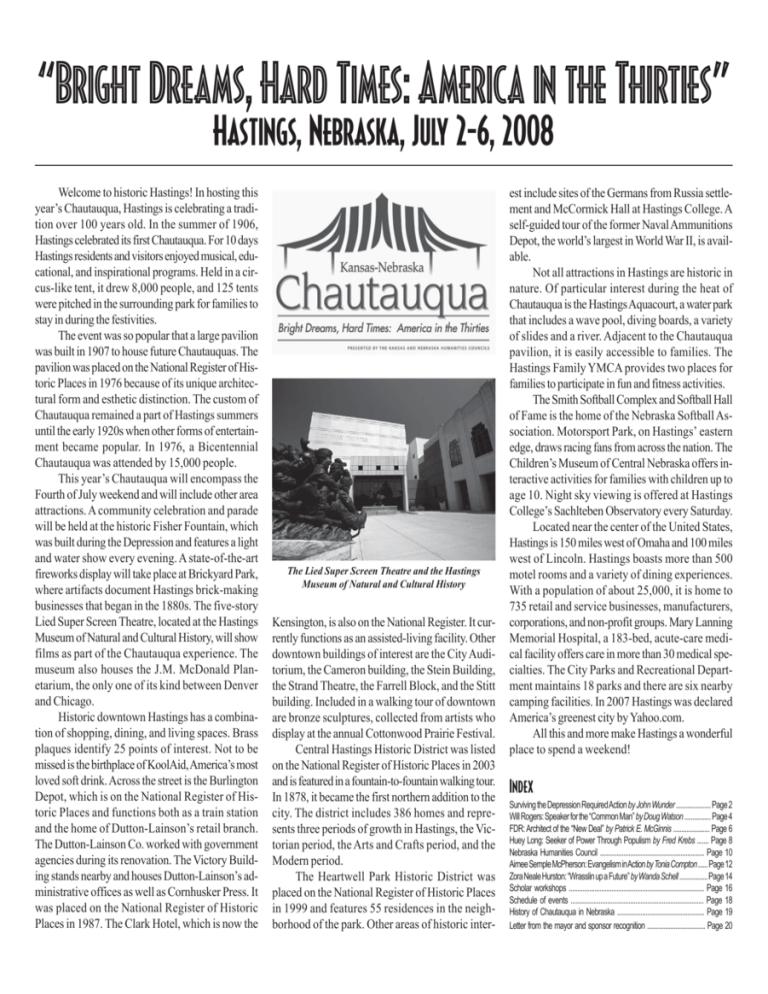

advertisement