Oxford-2012-handout - University of Delaware

advertisement

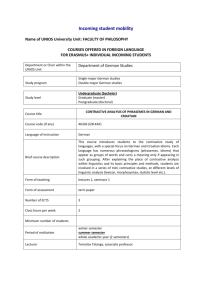

Patterns of Contrast in Phonological Change: Evidence from Algonquian Vowel Systems By Will Oxford Presented by Adam Breiner Previous research has described the triggering and spread of sound changes, other work has examined the role of phonetic factors in sound changes, as well as the relationship between these factors, and the synchronic phonology. However, as Oxford puts it, “This article will examine the role of an even more basic phonological notion: contrast. It will be argued that a simple model of the diachronic role of contrast allows us to identify underlying relationships among sound changes that would not otherwise be evident (P.2, Oxford).” Oxford intends to demonstrate these underlying relationships using Algonquin vowel systems. 1. Contrast and Sound Change The Contrastivist Hypothesis: Only contrastive features are phonologically active (Hall 2007). We can determine a contrastive feature using the “Minimal Pairs” method. This creates a logical issue, however. What if we added another logically possible feature to a comparison of vowels? Now consider an approach utilizing the Contrastive Hierarchy (Jakobson, Fant, and Halle 1952): So, what does this mean for the Contrastivity Hypothesis? It means that for such a vowel /u/ in this language, rounding can only be triggered if [+round] is a contrastive feature. 2. Sound Changes “SUBSYSTEMS—partitions of the inventory that behave autonomously with respect to mergers, chain shifts, and phonetic dispersion (P.7).” Chain Shifts Generalizable- Apply within a subsystem as a unified rule. (Raising or Lowering) Sequential- Shifts across subsystem boundaries. X vowel goes to Y. Z vowel goes to X. Mergers Merger by Approximation- The phonetic target of /a/ converges with that of /b/, the outcome can be [a], [b], or an intermediate segment [c]. Merger by Transfer- /a/ is replaced by /b/ categorically, but diffuses over time through the lexicon. Merger by Expansion- Phonetic ranges of /a/ and /b/ expand until they are “coextensive,” occupying the same area, resulting in a phoneme-allophone relationship Conditioned Merger- Contrast is lost in a certain environment Unconditioned Merger- Contrast is lost everywhere Mutation Merger- When an assimilatory process’s environment becomes opaque, leading to two UR’s being possible for a given surface form. This is a form of partial merger. (P.9) Structural Mergers- A situation in which the contrast between two segments disappears. Example: (pin-pen merger) The life cycle of a phonological process a. Articulatory, acoustic, or auditory phenomenon b. Language-specific pattern of gradient phonetic implementation c. Categorical phrase-level phonological process d. Categorical phonological process with narrowing domain (word, stem) e. Morphological process or lexicalized residue An interesting set of processes, but particularly important because Oxford intends to speak about Algonquin using historical information about the phonology so he can access parts c and d of the cycle. Kiparsky states “that “sound change is not blind” in that it tends not to produce typologically unusual results, plausibly due to a learning bias that disfavours the selection of unusual innovations. With regard to processes, Kiparsky suggests that assimilation should not be able to spread the unmarked value of a feature and that neutralization should favour the unmarked value. (P.10)” 2.3 Rerankings of the Contrastive Hierarchy: Previous Work A proposed contrastive hierarchy reranking from Hong Kong Cantonese (Barrie 2003): So what does this mean? It explains why /i:/ can no longer trigger palatalization. Other work on Korean and Mongolic by Ko establishes another hypothesis for working with the Contrastive Hierarchy diachronically. Minimal Contrast Hypothesis: Phonological merger is restricted to pair of segments that differ only in the value of the lowest-ranked contrastive feature. 2.3.2 Modeling Contrast in Sound Change Sisterhood Merger Hypothesis: Structural Mergers apply to “contrastive sisters.” A contrastive sister is a feature on the same “branch.” Observe 11a on page 13. Only /y/ can merge with /i/. Contrast Shift Hypothesis: Contrastive hierarchies can change over time. Contrast shift is recognized by Oxford as an important locus of phonological change, and typology. A constraint: The contrast shifts must be “as minimal as possible, ideally involving either the addition or deletion of a single contrast or the reranking of a single contrast by a single step. (P.15)” Forces which influence contrast shift: Drift- The tendency for successive changes to continue in the same direction along a given dimension. Markedness- The tendency for changes to disfavor typologically unusual properties. Symmetry- Favors changes which increase the symmetry of the inventory. And finally, one last hypothesis! Segmental Reanalysis Hypothesis: A segment may be reanalyzed as having a different contrastive status. What does this mean? Effectively, a segment that was once contrastive because of a given feature, can be reanalyzed to be contrastive for a separate one. “Before proceeding, it is worth clarifying that this article offers a model of the phonological implications of sound change, not a model of sound change itself. The single-minded focus on contrast in the following sections may give the misleading impression of a “phonology-first” theory of change, but the actual goal is simply to isolate those aspects of sound change that are phonologically relevant— regardless of their ultimate cause—and extract their contrastive implications. (P.18)” For convenience, the four hypotheses in one place: Contrastivist Hypothesis: Only contrastive features are phonologically active. Sisterhood Merger Hypothesis: Structural mergers apply to “contrastive sisters.” Contrast Shift Hypothesis: Contrastive hierarchies can change over time. Segmental Reanalysis Hypothesis: A segment may be reanalyzed as having a different contrastive status. 3. Algonquin Sound Change Proto-Algonquian is compared with Proto-Algic at first. It is a language spoken from the western plains to the eastern seaboard of North America. The languages are generally separated into Central, Plains, and Eastern subgroups. Oxford’s study concerns some from each of these groups. They are as follows: 3.2 A Phonological sketch of Proto-Algonquian vowels Above, Oxford posits a possible trajectory for the languages sound changes, using a merger of expansion. From here, the processes from above are used, as well as the hypotheses from earlier are used to create a contrastive hierarchy for Proto Algonquin: Let’s discuss the logic behind a few of these decisions in the tree. Proto-Algic The same vowel system: So, we know that Proto Algonquin merged /i, ɛ/, resulting in a height contrast. As well, Yurok and Wiyot merged each of these vowels with its long counterpart. From this, we can say that at some point in these languages [low] > [long]. How do we know this? How does the principle of drift apply here? What should we expect to occur? The final hierarchichal ranking of features is given in (29): [labial] > [coronal] > [long] > [low] 4. An Examination of Sound Change in Various Dialects of Algonquin A conventional note: Oxford eventually addresses about 20 different sound changes. For the sake of brevity, I have included one from each family. We can go through as many as we have time for, and that the class is interested in! Menominee: Menominee underwent a phenomenon where many new vowel phonemes emerged. This was called the “Great Menominee Vowel Shift.” The shift is described as follows: 1. Front vowel lowering: PA */i/ > /e/ and */ ɛ/ >/ æ/ 2. Glide-vowel coalescence creates a new phoneme /i/. 3. Raising of /e,o/ to /i,u/ when /i/ or a post-consonantal glide follows later in the word, and /æ/ does not intervene. Change 1 can be accounted for simply using the hierarchy for Proto-Algonquin. Change 3 requires the addition of another contrast within coronal. Observe: Oxford states that this raising created a synchronic alteration that we can regard as vowel harmony. Observe the following data: D D 5. Eastern Algonquin Sound Change Beginning with Proto-Eastern Algonquin, there were two major vowel shifts.: The contrastive hierarchy appears for PEA as follows, in stages: The second stage appears as follows, with high as the new highest ranked contrast. Finally, the length contrast is lost in PEA for /u:/ and /i:/, so the final hierarchy is as follows: 5.1 Sound Change in the Delaware Languages: Munsee and Umami First, a few changes which occurred, as shown in these vowel charts: The goal of these changes is to reduce asymmetry in the inventories. The length contrast was extended across all the vowels, and the labial contrast was extended to all the non high vowels utilizing /ɔ ɔ:/. “The fact that we can straightforwardly characterize the Delaware changes as filling the contrastive gaps in the PEA system provides a retroactive confirmation of the asymmetrical analysis proposed for PEA.” I found this example to be particularly salient for understanding the force of symmetry in the contrastive hierarchy. 6. Plains Algonquian Vowel Reflexes: Blackfoot Blackfoot exhibited several changes in its vowel inventory. Observe the chart below: As well, there was a partial merger of */a/ with */i/. This could only occur given a shift in the ranking: [labial] > [long] > [coronal] > [low] An interesting note is that */o/ can trigger rounding. Remember the principle earlier, that only contrastive features are phonologically active. Assibilation can also be discussed here. First, /k/ became /ks/ before /i(:)/, while /t/ became /ts/ before /i(:)/. So, Oxford argues that if we regard assibilation as a type of palatalization, then the fact that /i(:)/ triggers it signals that it is indeed contrastively [coronal.] 7. Discussion “This article has described approximately fifty diachronic changes and accounted for them by positing a smaller number of contrast shifts. (p.62)” (These are listed on pages 62-65). “The assumption of these shifts allows nearly all of the above changes to be accounted for under a restrictive model of phonological change that obeys the Contrastivist Hypothesis and the Sisterhood Merger Hypothesis. (p.66)” “The contrastive approach to phonological change is beneficial not only in providing a principled account of a wide range of developments, but also in the relationships and patterns that it uncovers among these developments,many of which would not otherwise be obvious. (p.66)” “When a single contrast shift accounts for more than one subsequent development, we gain an insight into these developments, as they can now be seen as related effects of the same underlying cause rather than separate, unrelated innovations. (p.67)” The list of these includes the promotion of [long] in PA, the reanalysis of [low] as [high] in CreeMontagnais-Naskapi, restructuring of the PEA vowel system according to [high], place asymmetry in the PEA vowel system, and promotion of [long] in Massachusett. 7.3 Accounting for Changes using Vowel Inventory Structure There are two divergent vowel inventory structures in these languages: Given these systems, we can see the effect of the phonological analysis given above when one considers the changes which have occurred in related languages. Observe what occurs with mergers involving /ɛ/: “We have thus formulated not only a synchronic analysis of these typologically unusual processes, but also a diachronic analysis in which their peculiar conditioning falls out from the same contrast shift that accounts for the occurrence of high-vowel mergers and repeated */ɛ, a/ interactions in related languages as well as the consistently different patterning of similar processes in the other branch of the family. Recognizing patterns of contrast in historical phonology provides a unified explanation of this large set of developments. (p.71)” 8. A Brief Conclusion “In its application to the Algonquian data, the model proposed in this article has provided a coherent and constrained framework for analyzing the phonological structure of an entire language family and revealing unified diachronic and cross-linguistic patterns in developments that might otherwise appear to be random. The hierarchically-constrained model of mergers and shifts also provides an explicit formalization of the notion of subsystems that Labov (1994) has shown to be central to sound change, thus creating a new connection between theoretical and variationist perspectives on phonology. (p.74)” References Oxford, Will. "Patterns of contrast in phonological change: Evidence from Algonquian vowel systems." Ms., University of Toronto (2012).