A MECHANISTIC STUDY OF COMPLEX BASE

advertisement

A MECHANISTIC STUDY OF COMPLEX BASE-PROMOTED

1,2-ELIMINATION REACTIONS

by

ALAN PAUL CROFT, B.S.

A DISSERTATION

IN

CHEMISTRY

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty

of Texas Tech University in

Partial Fulfillment of

the Requirements for

the Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

Approved

^-^

uecemoer, i^oj

7 -^

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my gratitude to my wife, Denise,

and to my family for their support and understanding during

the course of this research.

I would also like to acknowledge

the invaluable assistance of Professor Richard A. Bartsch.

Without his encouragement and guidance, this dissertation

would not have been written.

Acknowledgement is also made to the Donors of the

Petroleum Research Fund, administered by the American Chemical

Society, for support of this research.

11

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES

I.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanisms of Base-Promoted 1,2-Eliminations Which

Form Alkenes

. . ..

Fundamental Mechanisms

Variable E2 Transition State Theory

Probes of Mechanism and Transition State Structure

..

Variation in Structure of Elimination Substrate

..

Variations in Base and Solvent

Kinetic Isotope Effects

Stereochemistry of E2 Elimination Reactions

Introduction

Anti vs. Syn Elimination

Orientation in E2 Elimination Reactions

Formulation of Research Plan

Complex Base-Induced Elimination - Background

Statement of Research Problem

II.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Preparation of Substrates

trans-1,2-Dibromocycloalkanes

trans-1,2-Dibromocyclobutane

trans-1,2-Dibromocyclopentane

trans-1,2-Dibromocyclohexane

•• •

111

. . ..

trans-1,2-Dibromocycloheptane

30

trans-1,2-Dibromocvclooctane

30

trans-1,2-Dichlorocvcloalkanes

30

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclopentane

30

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclohexane

30

trans-1,2-Dichlorocycloheptane

31

trans-1,2-Dichlorocvclooctane

31

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane

31

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocycloalkanes

32

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclobutane

32

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclopentane

34

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane

35

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocycloheptane

35

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclooctane

35

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocycloalkanes

36

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocyclopentane

36

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocyclohexane

36

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocycloheptane

36

trans-l-Halo-2-methoxycycloalkanes

37

trans-l-Chloro-2-methoxycyclopentane

37

trans-l-Bromo-2-methoxycyclohexane

37

trans-l-Chloro-2-methoxycyclohexane

38

trans-l-Fluoro-2-methoxycyclohexane

38

trans-l-Chloro-2-methoxycycloheptane

38

cis-1,2-Dichlorocycloalkanes

IV

....

39

cis-1,2-Dichlorocyclopentane

39

cis-1,2-Dichlorocvclohexane

40

cis-1,2-Dichlorocvcloheptane

40

cis-1,2-Dichlorocvclooctane

40

cis-1,2-Dichlorocvclododecane

40

ll,12-Dichloro-9,10-dihydro-9,10-ethanoanthracenes

, .

41

trans-11,12-Dichloro-9,lO-dihydro-9,10-ethanoanthracene

41

cis-11,12-Dichloro-9,lO-dihydro-9,10-ethanoanthracene

42

trans-2-Chloro-l-cyclohexvl Phenyl Sulfide and Sulfone.

42

trans-2-Chloro-l-cyclohexyl Phenyl Sulfide

42

trans-2-Chloro-l-cyclohexyl Phenyl Sulfone

42

Miscellaneous Elimination Substrates

43

trans-l-Chloro-2-tosyloxycyclohexane

trans-[(2-Chlorocyclohexyl)oxy]trimethylsilane

43

...

43

trans-2,3-Dichlorotetrahydropyran

44

(E)-l,2-Dichloro-l-methylcyclohexane

44

Preparation of Authentic Samples of Elimination Products.

1-Bromocycloalkenes

45

45

1-Bromocyclobutene

45

1-Bromocyclopentene

45

1-Bromocyclohexene

45

1-Bromocycloheptene

....

46

1-Bromocyclooctene

46

1-Chlorocycloalkenes

46

1-Chlorocyclobutene

46

V

1-Chlorocyclopentene

45

1-Chlorocyclohexene

47

1-Chlorocycloheptene

47

1-Chlorocyclooctene

47

(E)-l-Chlorocyclododecene

47

(Z)-l-Chlorocyclododecene

48

1-Methoxycycloalkenes

49

1-Methoxycyclopentene

49

1-Methoxycyclohexene

49

1-Methoxycycloheptene

49

3-Methoxycycloalkenes

50

3-Methoxycyclopentene

50

3-Methoxycyclohexene

51

3-Methoxycycloheptene

51

Cyclohexen-1-yl Phenyl Sulfides and Sulfone

51

1-Cyclohexen-l-yl Phenyl Sulfide

51

2-Cyclohexen-l-yl Phenyl Sulfide

52

1-Cyclohexen-l-yl Phenyl Sulfone

52

Miscellaneous Elimination Products

53

ll-Chloro-9,10-dihydro-9,10-ethenoanthracene

....

53

(1-Cyclohexen-l-yloxy)trimethylsilane

53

5-Chloro-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran

53

Procedures for Elimination Reactions

54

Complex Base-Induced Eliminations

54

Preparation of Complex Base

VI

54

Standard Complex Base Elimination Procedure

Competitive Complex Base Elimination Procedure

....

54

...

55

Control Experiments

55

Eliminations Induced by Potassium t^-Butoxide in

_t^-Butanol

55

Preparation of t^-BuOK-t^-BuOH

56

Elimination Procedure for t^-BuOK-t^-BuOH

57

Control Experiments

57

Gas Chromatographic Analysis

III.

57

Compound Purity Determinations

58

Analysis of Elimination Reaction Mixtures

58

Molar Response Studies

59

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

64

Synthesis of Elimination Substrates

64

Mechanistic Features of Complex Base-Induced

Elimination

66

Nature of the Complex Base

72

Effect of Ring Size Variation upon Competitive

Dehydrobromination and Dehydrochlorination Promoted

by Complex Base and by t^-BuOK-_t-BuOH

Competitive Syn and Anti Dehydrochlorination

Induced by Complex Base

Leaving Group and B-Activating Group Effects

81

87

....

97

x-Activating Group Effects

108

Elimination from Substrates with Non-halogen

6-Activating Groups

112

Vll

I^v

IV.

CONCLUSION

121

LIST OF REFERENCES

123

APPENDIX

128

Vlll

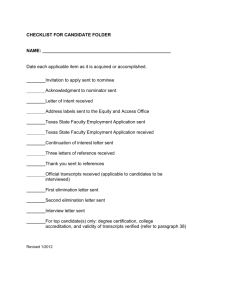

LIST OF TABLES

1.

Effect of Solvent and Crown Ether on Syn and Anti

Contributions for _t-BuOK-Promoted Eliminations

from 5-Decyl Tosylate

19

2.

Molar Response Values

60

3.

Elimination Reactions of trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane Induced by NaNH2-NaOCR-^R^R-^ in THF

at Room Temperature

73

Elimination Reactions of trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane Induced by NaNH2-NaAnion in THF at

Room Temperature

79

Syn Eliminations from trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocycloalkanes Promoted by Base

83

Competitive B-Halogen Activated Syn and Anti Dehydrochlorination from ^ and 2_4, or ^ and l^. ^'^~

duced by NaNH2-NaO-_t-Bu in THF at 20.0°C

91

Competitive Syn and Anti Dehydrochlorination from

cis- or trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane Induced

by NaNH2-NaO-_t-Bu in THF at Room Temperature, or

_t-BuOK-_t-BuOH at 50.0°C

95

Leaving Group Effects for Eliminations from trans1,2-Dihalocycloalkanes Promoted by NaNH2-NaO-_t-Bu

in THF at 20.0°C

101

B-Activating Group Effects for Eliminations from

trans-1,2-Dihalocycloalkanes Promoted by NaNH2Na0-_t-Bu in THF at 20.0°C

102

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Leaving Group and B-Activating Group Effects for

Syn-Exo Eliminations from 2,3-Dihalonorbornanes

Promoted by Sodium Pentoxide in Pentanol at 110°C

. . .

104

Dehydrohalogenations from Elimination Substrates

Containing Non-halogen B-Activating Groups, Induced by NaNH2-Na0-_t-Bu in THF

114

Dehydrohalogenations from Elimination Substrates

Containing Non-halogen B-Activating Groups, Induced

by t-BuOK-t-BuOH at 50.0°C

116

IX

LIST OF FIGURES

1.

Variable E2 Transition States

7

2.

More 0*Ferrall Potential Energy Surface for Elimination

Reactions

9

3.

Newman Projections of Selected Elimination Stereochemistries

16

4.

B-Halogen Activated Syn and Anti Dehydrochlorination . . .

89

5.

Competitive Syn and Anti Dehydrochlorination from cisor trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane

94

Schematic Representation for the Possible Elimination

Pathways for Competitive Reaction of Two trans-1,2Dihalocycloalkanes with Complex Base

99

6.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Elimination reactions are among the most widely studied reaction types in organic chemistry.

The chemical literature abounds

with reports of research dealing with the "elimination" of various

groups from substrates which yield new compounds. Most common

are those eliminations in which a proton and a leaving group are

removed from two neighboring carbon atoms, respectively.

This

1,2- or B-elimination is most often seen in alkene-forming eliminations.

However, alkynes, imines, and carbonyl compounds can also

be the products of 1,2-elimination reactions.

In this introductory

section, the fundamental mechanisms of alkene-forming eliminations

will first be surveyed.

Thereafter, mechanistic considerations

and the experimental techniques which are most commonly employed

in mechanistic elucidation of these reactions will be discussed.

Finally, the discussion will be focused upon the special area of

complex base-induced elimination reactions.

Mechanisms of Base-Promoted 1,2-Eliminations

Which Form Alkenes

Fundamental Mechanisms

In the course of an elimination reaction, the substrate molecule must undergo a series of bond breaking and bond forming steps.

Generally two bonds within the substrate molecule must be broken,

and at least one bond is formed as the substrate undergoes elimina-

tion to form the product. The timing of this bond rupture and

formation, together with other mechanistic considerations affords

a variety of mechanistic possibilities. These mechanistic possibilities include both concerted and stepwise processes, which can

vary in regard to the electronic distribution and atom geometries

in the transition state(s).

Three fundamental mechanisms, which

are located at the two extremes and in a central position along a

mechanistic spectrum have been proposed.

The actual mechanism

for a given elimination reaction can be thought of as being a

modification of one of these three general types.

The most common type of elimination is the base-induced loss

of HX (where X is a suitable leaving group) from adjacent carbon

atoms in an organic substrate. This reaction has been known for

12

2

many years ' and has been the basis of much study.

accepted mechanism

A presently

(Equation 1) accounts for the often observed

second-order kinetics (first order in base and first order in substrate) of many of these reactions by proposing that the removal

of the B-hydrogen by the base is synchronous with the loss of the

B

H

H

»

B

+ -C"

I

•C-

I

X

—C

I

I

C'

^ BH 4^C3ZC"+ X

(1)

leaving group X, Hanhart and Ingold

3

designated this mechanism E2,

signifying "elimination, bimolecular."

This mechanism stands central

in the mechanistic spectrum, since bond rupture and bond formation

are proposed to occur in concert. While the concerted nature of

bond breaking and forming is inherent in the E2 mechanism, the extent

to which the various bonds have been broken or formed may vary widely.

This variation will be discussed in more detail later in this introductory section.

In addition to the simultaneous loss of H and X in an elimination reaction, one can envision a process in which the leaving

group X has departed (i.e., C-X bond rupture is complete) prior

to loss of the proton.

Such a mechanism, the El, is illustrated in Equation 2,

,

H

^ 1 . 1 .

H:

-c—c- Z

I

^ -c

I

<

X

K

c

— >

H"^ + C ~ C _ - X

(2)

+

^-1

x'

This El (elin.ination, uniraolecular) mechanism was first proposed

to explain the overall first order (in substrate) kinetics observed

for certain eliminations from alkyl halides which occur in solution

4

in the absence of added base.

(Equation 2):

The mechanism involves two steps

a slow ionization of leaving group to form a cationic

species, followed by the fast loss of the B-proton to give the

olefin,

A third mechanistic possibility, which lies at the opposite

end of the mechanistic spectrum from the El type, is the ElcB

process (Equation 3),

"

2

+

-C

I

'

This mechanism involves the loss of the

^1

C- <

BH + -C

I

k

»

X

^-1

k

C-

> BH +^CIZ:C^ X (3)

proton to the base (C -H bond rupture) prior to the beginning of

C -X bond scission.

The ElcB mechanism (elimination, unimolecular,

conjugate base) cannot generally be kinetically distinguis'-^ed

from the E2 if the carbanion goes on to give the alkene product

much more rapidly than it reverts to starting material. If

k^>>k .[BH ], and the conditions required for a steady state approximation are met, the rate law for this mechanism becomes second-order

overall (first order in base and first order in substrate).

Such

a process is kinetically indistinguishable from that for an E2

reaction and the mechanism is termed ElcB irreversible. However,

if the return of the carbanion to starting material is much faster

than its collapse to give the product (k_^[BH ]>>k^), a rate law

is generated which is still first order in substrate and in base.

but has an inverse first order dependence on the conjugate acid

of the base.

A reaction with such a mechanism can be kinetically

distinguished from E2.

An ElcB mechanism of another type, which can also be kinetically

distinguished from the E2 has been proposed by Bordwell

Rappoport.

and

If the B-hydrogen of the substrate is very acidic

and the leaving group is poor, the substrate would then be expected

to be converted very rapidly to the carbanion which would only

slowly undergo loss of the leaving group to give the product.

In this case, a steady state approximation would be invalid (due

to the high concentration of the carbanion), and k^ would be rate

determining.

Under these circumstances, the rate law would be first

order in substrate, but zero order in the base, since further addition of base would not increase the concentration of carbanion.

Recently, Jencks et al,

has developed a concept of "enforced

concertedness," which he has applied to certain elim.ination reactions.

These workers

propose a merging of mechanism which is

induced by the instability of the proposed intermediate.

Thus a

change from an ElcB mechanism to an E2 mechanism might more appropriately be described as a transformation within a single mechanism

rather than a change between two coexiting mechanisms.

by Jencks,

As envisioned

the carbanion of the ElcB process becomes increasingly

unstable with substrate modification until its lifetim.e becomes

less than one vibrational period of the C-X bond.

Therefore, the

intermediate carbanion ceases to be an intermediate (in a potential

energy well along the reaction coordinate) and exists only as a

transition state.

Thus substrate modification which leads to in-

creasing instability of the carbanion, "forces" the loss of the

leaving group to be concerted with the loss of the proton.

This

concept raises the question of whether the discrete mechanistic

types previously described are individual mechanisms, or are actually portions of a mechanistic continuum.

The particular mechanism to be followed by a given elimination

reaction, is therefore determined by a wide variety of factors

which includes the base-solvent system and substrate structure.

In addition, there may be considerable mechanistic variation within

each of the three broad classes of elimination mechanism just

discussed.

In this treatment, it is impossible to describe all

aspects of these variations.

monograph on the subject.

2

The reader is referred to an excellent

However due to its pertinence, the

subject of mechanistic variation within the E2 mechanism will now

be addressed.

Variable E2 Transition State Theory

In the complex area of mechanistic elucidation of bimolecular

elimination, it became apparent early that a large number of elimination reactions appear to proceed by the same gross mechanism (E2).

However, orientation and reactivity differences among these reactions

suggest differences in transition state characters (and energy

differences between reactant and transition state) for the various

2

E2 reactions.

A comprehensive mechanistic theory, known as the

Variable E2 Transition State Theory, was the culmination of work

2 8 9

by several researchers, * * and was first comprehensively presented

in Bunnett's 1962 review.

In its original and most basic form,

the theory attributes the observed differences within the myriad

of E2 eliminations to changes in the relative extents of bond rupture of the carbon-hydrogen and carbon-leaving group bonds in the

transition state.

This "spectrum" of E2 transition states is illus-

trated in Figure 1.

B

B

B

I

I

I

I

I

H

H

I

•C:

H

I

I

I

I

C-

•cI

I

r

I

I

I

X

ElcB-like

1

Figure 1.

I

I

-Cr-rrr:CI

:

X

X

Central

El-like

2

3

Variable E2 Transition States

A continuum of E2 transition states can be pictured which range

from the ElcB-like variety j^, which has appreciable C-H bond rupture,

but very little C-X bond rupture, to the El-like type 2» in which

appreciable C-X bond scission has occurred, but relatively little

8

C-H bond rupture has taken place.

At the center of this continuum

lies the central E2 transition state 2^, which has syncronous C-H

and C-X bond rupture.

A further possible variation in transition state structure

must also be considered.

Although the degrees of rupture of the

C-H and C-X bonds may be well matched (central E2 transition state),

both bonds may be broken to a greater or lesser extent, which controls the degree of double bond formation.

Thus, central E2 transi-

tion states can have a high degree of double bond formation (productlike transition state), or very little double bond character (reactant-like transition state).

Variations of this type are best understood when seen in the

context of a More O'Ferrall diagram

(Figure 2).

This very popu-

lar 12 schematic representation of the potential energy surface

allows for all variations of E2 mechanisms (as well as the El and

ElcB mechanisms) to be represented.

While more detailed information on the use of these diagrams

in the study of elimination mechanisms is available in a recent

1o

review article,

a basic discussion of these plots follows:

Along the X and Y axes of the plot are represented the C-H and C-X

bond orders, respectively.

The Z axis (out of the plane of the

paper) represents the potential energy.

The reaction "pathway,"

in terms of C-X and C-H bond ruptures, can be plotted from reactants

(lower left-hand corner) to products (upper right-hand corner).

Thus, an El mechanism, which involves rupture of the C-X bond prior

I

B

I

t^

+ H-C—C+ + X

I

BH + C—C + X

I

/

/

El-like

/

Productlike

Central

/

/

/

u

p

u

Central

/

D.

3

/

U

/

X

I

/

h

B

Reactantlike

Central

I I

+ H-C—C-X

I I

Figure 2.

ElcB-like

/

C-H rupture

_ I

BH +

I

C—C-X

I

I

More O'Ferrall Potential Energy Surface for Elimination

Reactions

to rupture of the C-H bond would be represented by a pathway following the left-hand, then top borders of the diagram; while a syncronous E2 elimination would be represented by a diagonal pathway

directly from the lower left-hand comer to the upper right-hand

corner.

Placement of the transition state along a given reaction

pathway can give rise to representations of early (reactant-like)

transition states, or late (product-like) transition states.

Perturbations in transition state character influenced by

changes in substrate structure (a- or B-substituent effects, leaving

group effects, etc.) can be predicted by employing three rules in

conjunction with these plots:

12

(1) if species corresponding to a

10

corner along the reaction coordinate are stabilized, the transition

state is moved along the reaction coordinate away from the stabilized corner (Hammond effect); (2) if species corresponding to a

comer perpendicular to the reaction coordinate are stabilized,

the effect is to move the transition state toward the stabilized

corner; (3) if the stabilization is both along and perpendicular

to the reaction coordinate, the movement of the transition state

will be the vector resultant of the movements described in the

earlier rules.

Therefore, these plots can be employed in assessing the relative effects of variations in the reaction upon the reaction mechanism.

The power of these plots is their predictive nature.

The

predictions arising from the use of these plots can then be the

subject of experiment.

Probes of Mechanism and Transition State Structure

While predictions of transition state structure which conform

to the experimentally observed constraints are perhaps possible

in simple processes by use of the Hammond Postulate

13

or by apply-

14

ing such theoretical approaches as the Swain-Thorton Rules,

application of these principles to the complex bimolecular processes

at hand is not straight forward.

Therefore determination of the

reaction mechanism and transition state structure(s) must rely

heavily upon experimental techniques, a brief discussion of which

follows.

11

Variation in Structure of Elimination Substrate

Several techniques have been employed in the study of elimination reaction mechanisms which are based upon identifying changes

in reactivity as a function of structural modification.

One such

technique, which has wide applicability to a great many organic

reactions, is the linear free energy relationship which is known

as the Hammett equation

16

(Equation 4 ) .

log r^o

=

pa

(4)

Reactions of substrates which bear m- and £-substituted phenyl

groups can often by correlated with Equation 4, where k is the rate

(or equilibrium) constant for the reaction of the substrate that

contains a substituted phenyl group and k

is the rate (or equili-

brium) constant for the reaction of the corresponding substrate

with an unsubstituted phenyl group.

The constant p is characteris-

tic of a particular reaction and the reaction conditions.

Rho is

a measure of the sensitivity of the reaction to changes in electron

density at the reaction site.

The constant o is characteristic of

the particular substituent and its position on the phenyl group.

Sigma (o) values have been defined for a number of substituents.

2

Use of this technique is limited to those elimination substrates

which contain a phenyl group (usually attached to the 6-carbon).

Hammett o values have been tabulated for a large number of elimination reaction systems.

2

Introduction of substituent groups at the a- or B-carbons

of an elimination substrate has been utilized in mechanism elucida-

12

tion by several workers

W.

,B

H—C

I

^B

For example, the introduction of

,a

C—X

I

^a

an electron-withdrawing group at a B position (R. in 4) should

p

—

exert a stabilizing influence upon a developing negative charge

at Cg.

However, if the group is bulky, a steric effect might also

be envisioned (such as hindrance of approach of base).

Since the

source of such substituent effects often cannot be unambigiously

determined (being a mixture of steric, electronic, and possibly

other factors) mechanistic conclusions which are based upon these

substituent effects must be carefully weighed.

Careful attention

to experimental design can often enhance the utility of such data.

Bunnett et al.

*

have proposed an "element effect," which

is perhaps better described as the leaving group effect in elimina12

tion reactions. For example, it has been shown,

that a sequential

variation of leaving group identity (varying X in 4_) often leads to

large differences in reaction rates and product distribution (in

cases where two or more products are possible).

very useful in mechanistic elucidation.

Typically, the order of

leaving group reactivity is I>Br>Cl>>F for

halogenations.

Such data can be

base-promoted dehydro-

However, the magnitude of this effect and the

reactivity ordering are dependent upon the particular reaction

13

system.

This will become evident to the reader in the latter sec-

tions of this work.

Variations in Base and Solvent

Early in the study of elimination reactions, it was noted

that changes of base and/or solvent often had a pronounced effect

upon the reactions of a given substrate.

It has now been shown

that these effects arise from several sources.

Interpretation

of the results requires consideration of such factors as base

strength, base size, identity of the atom at the basic center,

2

and ion pairing or aggregation effects.

For example, simply

replacing an ion-paired base with a "free" base can induce large

variations in the orientation of eliminations from a common substrate.

20

Similarly dramatic rate and orientation effects have

been observed in many cases by a change in solvent for a given base,

such as t_-BuOK from DMSO to t^-BuOH.

21

Attempts to correlate rate data with base strength for a particular set of reactions was suggested more than 60 years ago

by Br^nsted.

22

Application of the Br«insted rate law (Equation 5)

to a general base catalysed reaction allows a proportionality constant e to be determined when k (reaction rate constant), K^ (ionization constant for the base, and G (a constant) are known.

However,

log k = B log K^ + log G

(5)

3 may be experimentally determined without the value of log G being

known.

Although B was formerly taken as a measure of the degree of

proton transfer to the base in the transition state, recent con-

14

siderations indicate that interpretation of these Br^nsted coefficients is more complex and that B may not be a reliable indicator

of transition state character.

Kinetic Isotope Effects

Kinetic isotope effects are reaction rate differences which

arise from the substitution of an atom in a substrate with a heavier

isotope of the same atom.

The theoretical basis of these effects

will not be described here. However, the reader is directed to

Saunders and Cockerill^s excellent discussion of these effects

2

as they relate to elimination reactions. The most common isotope

effects

which have been reported for elimination reactions are

deuterium isotope effects which arise from the replacement of

protium with deuterium in a substrate. Most commonly, primary

deuterium isotope effects (k^/k^ = 4-7) are encountered.

These

effects are often taken as indications of the extent of C-H bond

rupture in the transition state. The isotope effect varies in a

gaussian manner with the extent of proton transfer in the transition state. The maximum effect should be seen when a proton is

half transferred in the transition state. However, interpretation

of intermediate values for k-u/k-. is complicated by the gaussian

character of the effect.

For example, 25% and 75"! transfer of a

proton in the transition state would lead to similar values for

kp/k-.

A further complication is quantum mechanical "tunneling,"

which can lead to erroneous conclusions about transition state

character which are based solely upon deuterium isotope effects.

23

15

Recently, other kinetic isotope effects in elimination reactions

(notably

CI-

CI) have been investigated.

These investigations

have provided additional insight into the mechanisms of selected

elimination systems.

Stereochemistry of E2 Elimination Reactions

Introduction

Another important aspect to be considered in examining the

mechanistic aspects of elimination reactions is stereochemistry.

The spatial arrangement of the pertinent atoms in the transition

state has important consequences in terms of reaction rate and

product identity.

While a continuum of possibilities exist for

the location of the leaving group relative to the B-hydrogen in

the transition state, two extreme cases and two intermediate cases

have received special consideration (Figure 3 ) .

25

In the nomenclature of Klyne and Prelog,

the conformation

which is obtained by rotation about the C -C

'

bond to give a dihe-

u p

dral angle of 180° is termed anti-periplanar (5) ; while syn-periplanar (6) corresponds to a dihedral angle of 0° conformations

5 and 6 are often referred to as those for trans and cis elimination in the chemical literature.

However, the use of the c j ^ and

trans nomenclature in the context of mechanism is insufficient to

describe fully the stereochemical course of the reaction, and might

be more appropriately applied solely to the products of the reaction.

Two other conformational variations are also recognized.

16

H

Anti-periplanar

Syn-periplanar

6

X

Anti-clinal

Syn-clinal

7

Figure 3.

8

Newman Projections of Selected Elimination Stereochemistries

Anti-clinal (7)

and syn-clinal (8^) arrangements represent dihedral

angles of 120° and 60°, respectively.

The consequences of a particular transition state conformation

in a given reaction will become evident as the dichotomy of anti vs

syn elimination stereochemistries is examined.

Anti vs. Syn Elimination

The classic work of Cristol

26

with the benzene hexachloride

(1,2,3,4,5,6-hexachlorocyclohexane) isomers demonstrated the general

17

preference for anti elimination stereochemistry which has been

termed the Anti Rule.

In his study, Cristol

26

found that 9^ (which

has all the chlorine atoms trans to each other and is only capable

of syn elimination) reacted with base 7,000-24,000 times slower

H

CI

CI

H

CI

than did the other benzene hexachloride isomers (which had the

possibility of at least one anti elimination pathway).

The anti rule, while having great historical precedent, is

not without exceptions.

Certain bridged ring substrates were

shown to exhibit preferential syn elimination.

2

An example of

such a system which exhibits the typical conformational rigidity

that characterizes these substrates, is found in the eliminations

from the 9,10-ethanoanthracene derivatives jLO^ and U^.

The reaction

1^; X = CI, Y = H

11; X = H, Y = CI

18

of U^ with sodium hydroxide in 50% dioxane-ethanol at 110°C (syn

elimination) proceeds 7,8 times faster than does the analogous

reaction with 1^ (anti elimination).

27

Syn elimination stereochemistry is facilitated by certain

base-solvent combinations.

Generally, this effect has been attri-

buted to the degree of association of the base with its counter

12

ion.

28

Zavada, Svoboda, and Pankova,

in their detailed analysis

of t^-BuOK-induced elimination from 5-decyl tosylate, have demonstrated that the degree of base association influences the stereochemical course of the reaction (Table 1). When an effective K

com-

plexing agent (dicyclohexano-18-crown-6) was present for the reactions which were conducted in benzene or t^-BuOH, or the reaction

was run in a solvent that is more capable of efficient solvation

of the base counter ion (DMF), enhanced anti elimination was noted.

This result is consistent with the proposal that ion pairs (or

29

aggregates) of t-BuOK are the actual base species. Sicher

has

proposed a cyclic six-membered transition state 1^ which includes

electrostatic interactions between the base counter ion M and the

leaving group X to account for such favoring of syn elimination

/

_ C ^

C-

\

/

\

\

/

H

\

\

/

\

\

s

/

B-

— —

12

-M

/

/

X

i

19

TABLE 1

12

Effect of Solvent and Crown Ether on Syn and Anti Contributions

for _t-BuOK-Promoted Eliminations from 5-Decyl Tosylate

jL-BuOK

tl-'

n-Bu-CH

-n-Bu

>

cis and trans

%

conditions

n-BuCH=CH-n-Bu

%

%

%

anti—>

trans

syn—>

trans

anti—>

cis

syn—>

cis

33.6

12.4

50.4

3.6

C^H^'fxlE

6 6

63.9

4.1

29.2

2.8

_t-BuOH

24.8

4.2

68.2

2.8

^t-BuOH+CE^

67.1

4.7

26.7

1.5

DMF

73.2

2.8

22.6

1.4

^6"6

^CE = dicyclohexano-18-crown-6

20

relative to anti by associated bases. Examination of transition

state 2^2^ shows that the preference for syn elimination may be

explained on geometrical grounds. While the syn elimination provides for a cyclic transition state 1^, anti elimination cannot

involve such a cyclic transition state without inducing serious

strain in the transition state structure.

Orientation in E2 Elimination Reactions

In addition to the consequences of transition state structure

just discussed, the role of orientation in these eliminations must

also be addressed.

When elimination substrates are employed which

might give rise to two or more olefins, the question of orientation

arises.

For example, elimination from a 2-substituted

(Equation 6) can give rise to three products in theory.

CH.

CH^CHCH^CH.

>

CH^ CH

C=C

E

+

E

The three

H

;C=C

H

butane

+ CH2=CHCH2CH3

C6)

CH^

products illustrate the two types of orientation which are encountered in elimination reactions. When elimination products from a

common substrate differ as to the position of the double bond, the

21

products are said to have different positional orientation.

Thus,

cis- and trans-2-butene have the same positional orientation but

have a different positional orientation than does the 1-butene.

When the former pair are compared, the products are seen to differ

in the positions of the methyl groups on the double bond (cis vs.

trans).

When such orientation differences are addressed, these

differences are termed differences in geometric orientation.

When considering orientation differences in elimination products produced by a common mechanism from the same substrate, product proportion differences are attributed to differences in transsition state character for the various products.

Since all product

pathways diverge from a single substrate, transition state-reactant

energy differences must be due solely to differences in transition

state character for the various product pathways. Therefore orientation data can be significant in mechanism elucidation, ij_ a

common mechanism can be established for the competitive product

forming pathways.

Elimination to produce the less substituted alkene is termed

1 30

Hofmann orientation, ' while Saytzeff orientation is used to

describe the predominant formation of the more substituted olefin

(the thermodynamically more stable product).

31

Both positional

and geometrical orientation are influenced by the leaving group

identify, the base and solvent Identify, and the alkyl structure

of the substrate.

While a detailed discussion of the many factors

involved will not be undertaken in this section, the reader should

22

be cognizant of the role orientation considerations play in the

elucidation of elimination reaction mechanisms.

sions of these effects are available elsewhere.

Detailed discus2

Formulation of the Research Plan

Complex Base-Induced Elimination-Background

Caubere has popularized the use of sodium amide-containing

32 33

complex bases in organic synthesis. *

These bases, which are

composed of equimolar mixtures of sodium amide and ±n_ situ generated sodium alkoxide (or sodium enolate) in ethereal solvents,

such as tetrahydrofuran, have been shown to promote novel elimina32 33

tion reactions to form alkene, diene or aryne products. *

These highly aggregated sodium amide-containing complex bases

have been shown to efficiently promote syn eliminations from trans1.2-dihalocycloalkanes.

Caubere and Coudert

34

have reported that

the reaction of trans-1,2-dibromocyclohexane with NaNH2-NaO-t^-Bu

in THF at room temperature (Equation 7) gives 60% of 1-bromocyclohexene (syn elimination of HBr) and 36% of cyclohexene (debromination product).

However, when either the sodium amide or sodium

alkoxide base component was employed alone under the same reaction

conditions, 70-90% of the starting dibromide was recovered and only

34

traces of 1-bromocyclohexene or cyclohexene could be detected.

These results are startling when compared with those obtained for

similar eliminations employing more common alkoxide base-solvent

systems.^^

In these cases,"^^ synthetically useful quantities of

23

NaNH -NaO-_t-Bu

Br

(7)

H

THF, Room Temp.

H

Br

60%

1-halocycloalkene products are not produced.

36%

The 3-halocycloalkene

and 1,3-cycloalkadiene products predominate.

The remarkable ability of complex base to facilitate preferential syn elimination has been the subject of only limited mechanistic study.

A cyclic six membered transition state interaction 13

has been proposed

32 33 36

' *

to account for the observed results.

This representation is similar to Sicher's transition state ] ^

which has been proposed to explain the facility of syn eliminations

which are promoted by associated potassium alkoxide bases as was

discussed earlier.

In 13, where B is the base, M the base counter

13

24

ion, and X is the leaving group, an electrostatic interaction

between the leaving group (X) and the base counter ion (M) is

suggested to account for the observed favoring facilitation of

syn elimination.

Similar interactions of the base counter ion

and the leaving group are not possible in an anti elimination transition state due to geometrical considerations.

29

Importance of the alkoxide component identity in the complex

base upon the outcome of the reaction of trans-1,2-dibromocyclohexane has also been assessed.

37

Twenty-five different NaNH^-

NaOR combinations were utilized in reactions with the dibromo

substrate.

Results show that ramified alkyl groups (R of NaNH„-

NaOR) are important for producing the desired syn elimination.

38

Bartsch and Lee

investigated the possibility that the appar-

ent syn elimination was actually a base-catalyzed isomerization of

an initial anti elimination product (Equation 8).

Reaction of

Anti

' Hu

(8)

Br

Eliminatio

Isomerisation

H

H

Br

H

3-bromocyclohexene with complex base gave no detectable 1-bromocyclohexene.

This established that no isomerization was occurring

under the conditions of the complex base-promoted elimination reaction

25

39 40

in further work, Bartsch and Lee ' discovered a surprising

propensity for loss of the normally "poorer" leaving group in these

complex base promoted eliminations.

While an ordering of leaving

group reactivity of I>Br>Cl>>F is generally'''^*"''^ observed for

base-promoted dehydrohalogenations (consistent with Bunnett's

element effect for E2 eliminations

) , a reversal of this leaving

group ordering was observed in reactions of trans-1,2-dihalocycloalkanes which contained two different halogen atoms.

ment

Thus, treat-

39,40

'

of trans-l-chloro-2-fluorocyclohexane or trans-l-bromo-2-

fluorocyclohexane with NaNH2-NaO-_t-Bu in THF at room temperature

gave 85% of 1-chlorocyclohexene or 1-bromocyclohexene (-HF products) , respectively.

In neither case, was any 1-fluorocyclohexene

(-HC1 or -HBr product, respectively) detected.

Treatment of trans-

l-bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane with the same complex base, allowed

for a comparison of the relative propensities for dehydrochlorination and dehydrobromination.

Dehydrochlorination was found to

predominate over dehydrobromination with 54% of 1-bromocyclohexene

(-HC1) and 30% of 1-chlorocyclohexene (-HBr) being detected.

Lee and Bartsch further demonstrated that this preferential

loss of the normally poorer leaving group was confined to elimination reactions with syn stereochemistry.

Thus, reactions of 1-bro-

mo-l-chlorocyclohexane and cis-l-bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane with

NaNHp-NaO-_t-Bu in THF at room temperature gave 99% of 1-chlorocyclohexene.

26

Statement of Research Probl em

Although a few mechanistic aspects of complex base-promoted

elimination reactions have been investigated, the majority of the

factors which control these reactions remain to be determined.

Investigation of these factors is

definitely warranted due to

the unusual potential synthetic exploitation which these reactions

possess.

A program of research is envisioned which has as its initial

goal the identification of the effective base species for these

elimination reactions.

Variation of the oxyanionic component of

the complex base should have a pronounced effect upon the relative

rates of competitive dehydrohalogenation from a mixed halide substrate of the trans-1,2-dihalocyclohexane type, if the oxyanion

is indeed the effective base.

Since six-centered transition states of the type illustrated

in 13 have been proposed for complex base-induced elimination

reactions, a variation of ring size for the mixed trans-1,2-dihalocycloalkane substrate will be utilized to assess the effect of this

parameter upon the competitive dehydrohalogenation reaction modes.

Transition state structures for competitive dehydrochlorination

and dehydrobromination will be further characterized by the determination of leaving group and B-activating group effects.

An

analogous determination is envisioned for competitive dehydrofluorination vs. dehydrochlorination.

In order to ascertain the degree to which syn eliminations

are facilitated relative to corresponding anti elimination processes,

27

ratios of anti/syn rate constants will be determined for competitive reactions of a series of cis- and trans-1,2-dichlorocycloalkanes with complex base.

A search for possible steric interactions between the substrate

and the complex base is also proposed, as is the investigation of

the electronic requirements in the transition state at the a-carbon.

These experiments will provide mechanistic insight into this

unique type of elimination reaction.

Further mechanistic under-

standing is essential for full utilization of complex base-promoted

reactions as novel preparative reagents for the synthesis of hitherto

difficult-to-obtain elimination products.

CHAPTER II

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

All compounds used in the preparation of substrates or authentic

samples of reaction products, or in the elimination reactions were

reagent grade unless otherwise specified.

All starting materials

in preparations of compounds and all reagents used in the elimination reactions (with the exception of some alcohols used in the

study of alkoxide variation, which came from various commercial

sources and were reagent grade) were obtained from Aldrich Chemical

Company, unless noted otherwise in the text of this chapter.

H NMR spectra were obtained using a Varian E14-360 or EM-360A

spectrometer.

IR spectra were obtained employing a Beckman Accu-

lab 8 spectrophotometer.

Elemental analyses were performed by

Galbraith Laboratories of Knoxville, Tennessee.

Three gas chromatographs were employed in the present research:

a Varian Aerograph Series 2400 flame ionization gas chromatograph

(isothermal column temperature capability), utilizing 1/8 inch

packed columns (Chromatograph A); an Antek Model 461 thermal conductivity gas chromatograph (isothermal column temperature) utilizing

1/4 inch packed columns (Chromatograph B); and a Varian Aerograph

Model 3700 capillary gas chromatograph with a FID detector and

temperature programming capability (Chromatograph C).

tographic columns were employed in the research:

Six chroma-

Column A - a

10 ft. X 1/8 inch column of 20% SE-30 on Chromosorb P, which was

utilized with Chromatograph A; Column B - a 5 ft. x 1/8 inch column

28

29

of 5% SE-30 on Chromosorb P, which was utilized with Chromatograph A;

Column C - a 20 ft. x 1/8 inch column of 15% Carbowax20M on Chromosorb P, which was utilized with Chromatograph A; Column D - a 10 ft.

X 1/4 inch column of 20% SE-30 on Chromosorb P, which was utilized

with Chromatograph B; Column E - a 0 . 2 0 m m x 2 5 m vitreous silica

capillary SE-30 column (WCOT) from SGE Corporation which was utilized

with Chromatograph C; and Column F - 20 ft. x 1/4 inch column of

15% Carbowax 20 M on Chromosorb P, which was utilized with Chromatograph B.

Detailed information on the gas chromatographic analyses

employed in this study is contained in a latter section of this chapter.

Preparation of Substrates

trans-1,2-Dibromocycloalkanes

trans-1,2-Dibromocyclobutane

The dibromide (0.34 g) was isolated by preparative GLPC (Column D

operated at 125°C) .^sa fortuitous side product (25%) of the reaction

of cyclobutene with N-bromoacetamide in 6 M aqueous HCl, which gave

trans-l-bromo-2-chlorocyclobutane as the major (75%) product.

Detailed information on the reaction to give the bromo chloride is

given vide infra.

analysis.

The dibromide gave a satisfactory elemental

Anal. Calcd for Q.^n^l2,ic^'. C, 22.45; H, 2.83.

Found: C,

22.55; H, 2.86.

trans-1,2-Dibromocyclopentane

40

The compound was available from the previous work by Lee.

30

Gas chromatographic analysis (Column A operated at 72°C) showed

the compound to be >98% pure.

trans-1,2-Dibromocvclnhfivanp

This dibromide had been prepared earlier by Lee,

and a sample

of the previously-prepared material was utilized after GLPC analysis

(Column A operated at 72°C) showed it to be >95% pure.

trans-1,2-Dibromocycloheptane

Cycloheptene (5.0 g) was treated with 8.0 g of bromine in

5.5 ml of carbon tetrachloride using the procedure reported for

the preparation of the analogous cyclohexyl analog.

'

Distilla-

tion of the crude material gave 10.3 g of the compound with bp 128130°/18 torr (Lit.

bp 137-138°/30 torr).

The homogeneity of the

product was demonstrated by GLPC (Column A operated at 100°C).

trans-1,2-Dibromocyclooctane

38

A sample prepared earlier by Lee

was employed.

A check of

purity by GLPC (Column A operated at 115°C) showed the material

to be >99% pure.

trans-1,2-Dichlorocycloalkanes

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclopentane

A previously prepared

40

sample of the dichloride was employed.

Purity was ascertained by GLPC analysis (Column A operated at 72°C)

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclohexane

40

Lee

prepared the dichloride previously.

A sample of this

previously prepared material was utilized after its purity was

31

demonstrated by GLPC analysis (Column A operated at

ll^'C),

trans-1,2-Dichlorocvcloheptane

Treatment of cycloheptene (5.0 g) with a slow stream of molecular chlorine in the dark, in analogy with a procedure reported

for the preparation of the cyclohexyl analog,

crude material.

gave 6 g of a

Careful distillation of this material gave 1.5 g

of the title compound (>99% pure by GLPC, Column A operated at

100°C), together with a 3.0 g fraction which was contaminated (20%)

with unidentified higher boiling compounds. Preparative GLPC of

the latter fraction (Column D operated at 200°C) yielded additional

pure dichloride.

The pure dichloride fraction boiled at 44-48°/

44

0.6 torr (Lit. bp 93-94°/ll-12 torr).

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclooctane

A sample which had been prepared by Lee

38

was employed.

GLPC

analysis (Column A operated at 115°C) showed the compound to be

>99% pure.

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane

cis-Cyclododecene:

Treatment of a commercial sample (DuPont)

of 1,5,9-cyclododecatriene (95% cis, trans, trans; 5% isomers of

other stereochemistry) with 100% hydrazine hydrate, oxygen (from air),

and a catalytic amount of cupric acetate in 99% ethanol according

to the procedure of Nozaki and Noyori

tative yield of cis-cyclododecene.

gave an essentially quanti-

The material (bp 64-65°/0.6 torr,

Lit.^^ bp 132-134°/35 torr) was found to be >99% pure and free of

the trans isomer by capillary GLPC (Column E).

However, for a

32

parallel reaction (same scale) in which absolute ethanol was used

as the solvent and a very fast stream of air was employed as the

oxygen source (which resulted in a maximum reaction temperature

>50°C), significant contamination by the trans-cycloalkene was

evident.

The infrared spectrum of the product was consistent with

the spectrum previously recorded.

46

trans-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane:

The dark reaction of cis-

cyclododecene (12,0 g) and molecular chlorine (slow stream) for

30 minutes during which the reaction temperature was not allowed

to exceed 40°C, followed by careful fractional distillation gave

the title dichloride.

The fraction boiling at 156-160°/1.5 torr

(3 g) was shown by capillary GLPC (Column E) to be >99% pure.

Another fraction (5.5 g) was shown by GLPC (same column and conditions) to be 92% pure.

The pot residue from the distillation

('V'lO g) was mainly composed of unidentified higher boiling compounds

(GLPC, same column and conditions).

The fraction of >99% purity

was submitted for elemental analysis. Anal. Calcd for ^]^2^22^'^2*

C, 60.76; H, 9.35.

Found:

C, 60.97; H, 9.37.

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocycloalkanes

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclobutane

Cyclobutene:

Cyclobutene was prepared in five steps from

cyclobutanecarboxylic acid (Ash Stevens, Inc.) by the method of

Weinstock, Lewis and Bordwell.

42

33

Cyclobutyl amine was prepared via a modified Curtis rearrangement from cyclobutanecarboxylic acid.

Thus, 28,4 g of the acid

was treated according to the reported procedure

47

with 50 ml of

H2S0^ and 20,15 g of sodium azide in 200 ml of chloroform for three

days at 40-50°C, followed by workup.

The resulting crude amine

('^'25 g as the syrupy amine hydrochloride) was employed directly

in the subsequent reaction.

Exhaustive methylation of the cyclobutyl amine was accomplished

first by refluxing 0.26 mole of the amine with 212 g of 88% formic

acid and 153 g of 35% formaldehyde solution overnight, as reported

48

previously.

48

Following the reported workup procedure

and distil-

lation, 10.6 g (bp 79-81°) of the N,N-dimethyl amine product was

obtained. Treatment of 10 g of this dimethyl cyclobutyl amine

49

with methyl iodide

(16.5 g) in 100 ml Et^O caused the immediate

precipitation of the quaternary ammonium salt which, ^^en filtered

and dried, was found to represent a quantitative yield based upon

the N,N-dimethyl amine starting material.

Replacement of hydroxide for iodide as the counter ion of the

quaternary amine salt was accomplished with Am.berlite IRA-400-OH

ion exchange resin according to a published procedure

analogy to a previous report.

42

and in

Thus, 24 g of the iodide (dissolved

in 100 ml H^O) was passed over 100 g of the exchange resin contained

in a 1 inch diameter X 3 ft. glass column,

Elution with water,

followed by evaporation yielded 17 g of the quaternary hydroxide.

34

Cyclobutene was prepared by the pyrolysis of the syrupy quaternary hydroxide.

Following the method of Roberts and Sauer,

the

syrupy quaternary amine hydroxide from the last step was added

dropwise to a flask held at 130-150°C, and under vacuum (50-70 torr,

aspirator).

The evolved gases were passed through 1 N HCl (aq) and

the cyclobutene was collected in a trap cooled by Dry Ice-acetone.

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocvclobutane:

Cyclobutene ("^3 g) which

had condensed in the Dry Ice-acetone trap was allowed to bubble

slowly through a mixture of 27.5 ml of 6 M HCl (aq.) and 7.6 g

N-bromoacetamide at -10°C by allowing the trap to warm slowly.

When the flow of cyclobutene ceased as the trap temperature reached

room temperature, dry nitrogen was swept through the trap and it

was heated to '^'50°C. The reaction mixture was worked up (ether

extraction, washing of the organic layer v;ith water, 10% aq. NaHCO,,,

10% aq, Na^CO-, and water) as specified for the preparation of

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane

40

(vide infra).

Preparative GLPC

(Column D operated at 125°C) afforded 1.03 g of the pure trans-1bromo-2-chlorocyclobutane.

A small amount (0.34 g) of trans-1,2-

dibromocyclobutane was also collected as a side product. Anal. Calcd

for CH.BrCl:

4 o

C, 28.35; H, 3.57.

Found:

C, 28.54; H, 3.61.

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclopentane

A previously prepared

40

sample of this compound was available.

The purity was determined to be >98% by GLPC analysis (Column A

operated at 72°C).

35

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane

The method of Lee was followed.

Simultaneously, cyclohexene

(32.8 g) was added dropwise and 55.2 g of N-bromoacetamide was added

in portions to 200 ml of 6 M HCl at -8°C.

Following the additions

(which took "^AO minutes, during which the temperature of the reaction mixture never exceeded -5°C) the mixture was allowed to stir

an additional 30 minutes.

After the stirring period was complete,

the organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted

twice with diethyl ether.

The combined organic fractions were

washed (water, 10% aq. NaHCO^), dried (CaCl2), and the ether was

evaporated under reduced pressure.

(Lit.

40

Distillation (bp 73-74°/4.5 torr

bp 48-49°/0.95 torr) of the residue gave 37.0 g of the title

compound, which was found to be >95% pure by GLPC (Column A operated

at 72°C).

trans-1-Bromo-2-chlorocycloheptane

Reaction of cycloheptene (5.0 g) with N-bromoacetamide and

6 M HCl under the identical reaction conditions and times described

above for the preparation of the cyclohexyl analog gave (following

distillation) 8.2 g of the title compound (>98% pure by GLPC,

Column A operated at 100°C).

18 torr.

The purest fraction boiled at 116-118°/

Anal. Calcd for C^H^2^^^1=

^' 39.74; H, 5.72.

Found C,

39.94; H, 5.69.

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclooctane

The title compound was available from a previous preparation.

A purity of ^99% was determined for this sample by GLPC (Column A

operated at 115°C).

38

36

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocycloalkanes

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocyrlnppnfanp

A sample of the chlorofluoride was available from previous

, 40

work.

A second preparation of the compound based upon the previ40

ously reported method,

(same scale and procedure used to prepare

the cyclohexyl analog, vide infra) proved to be troublesome, giving

an orange solid as the major product.

The desired compound which

was the minor product (25%) boiled at 90°C (Lit.^^ bp 62-63°/132

torr), and was shown to be >97% pure by GLPC (Column A operated at

72°C).

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocyclohexane

The method of Lee was followed.

40

Diethyl ether (50 ml) and

HF/pyridine (Aldrich) were mixed in a 500 ml polyethylene bottle

without a cap and cooled to 0°C.

N-Chlorosuccinimide (13.0 g)

was introduced with stirring, and then 8.0 g of cyclohexene was

added slowly while the temperature was held below 10°C.

Following

addition of all reaction components, the mixture was allowed to

warm to room temperature and stir for 30 minutes.

Then, the reac-

tion mixture was poured into 300 ml of ice-water.

The ether layer

was separated, washed (water, 10% of HCl), dried (CaCl2) and dis40

tilled to give 4.0 g of the product (bp 30-31°/3 torr. Lit.

bp

51-52°/l4 torr).

Purity was demonstrated to be >99% by GLPC (Col-

umn A operated at 72°C).

trans-l-Chloro-2-fluorocycloheptane

Treatment of cycloheptene (4.6 g) with

HF/pyridine and N-chloro-

succinimide in diethyl ether by the method described above for the

37

cyclohexyl analog gave 3.0 g of crude trans-l-chloro-2-fluorocycloheptane, which was contaminated with 15% of undetermined higher

boiling compounds.

Careful distillation gave 0.7 g of the material

(bp 82-83°/18 torr) which was shown (GLPC, Column A operated at

105°C) to be 95% pure. Anal. Calcd for C^H

Found:

ClF:

C, 55.81; H, 8.03.

C, 56.01; H, 8.26.

trans-l-Halo-2-methoxycycloalkanes

trans-l-Chloro-2-methoxycyclopentane

Cyclopentene (19.9 g), N-chlorosuccinimide (39.0 g) and dry

methanol (120 ml) were placed in a 250 ml round-bottomed flask

fitted with a reflux condenser to which a CaCl^ drying tube was

attached.

The reaction mixture was stirred magnetically at room

temperature for 3 days.

Following the reaction, the mixture was

poured into 400 ml of ice-water and extracted with Et20.

The ether

layer was washed successively with water, 10% aqueous HCl, and water

again.

The ethereal solution was dried over CaCl2 and distilled

to produce 10.0 g of the 98% pure (capillary GLPC, Column E) material

(bp 54-56°/10 torr), together with an additional 8.5 g of the title

compound which contained 7% of contaminants. Anal. Calcd for

C,H,,C10: C, 53.53; H, 8.24. Found:

6 11

trans-l-Bromo-2-methoxycyclohexane

C, 53.64; H, 8.34.

A sample of the title compound was available from previous work

by Lee.

This sample was employed in the present research after

analysis by capillary GLPC (Column E) showed the compound to be >99%

pure.

38

tran£-l-Chloro-2-methoxycyclohexane

Material prepared previously

38

was subjected to preparative

GLPC (Column D operated at 165°C) to remove contaminants. The

chromatographed material was shown to be >99% pure by capillary

GLPC (Column E).

trans-l-Fluoro-2-methoxycyclohexane

_trans-2-Fluorocyclohexanol:

was employed.

The method of Wittig and Mayer

Thus, reaction of cyclohexene oxide (28.0 g) and

potassium hydrogen fluoride (33.0 g) in diethylene glycol (55 g ) ,

followed by distillation (bp 80-85°/18 torr, Lit.^"*" bp 65-70°/14 torr)

gave 25 g of the product.

The material was shown to be >99% pure

by capillary GLPC (Column E).

trans-l-Fluoro-2-methoxvcvclohexane:

The methylation of trans-

2-fluorocyclohexanol proceeded according to a published report.52

Thus, 4.8 ml of Mel, 12.0 g of silver oxide, and 3.1 g of the

fluoro alcohol were stirred at room temperature in 30 ml of DMF for

24 hours. Distillation of the worked up material (bp 46°/12 torr,

Lit.

52

bp 41°/11 torr) gave trans-l-fluoro-2-methoxycyclohexane,

which was >99% pure (capillary GLPC, Column E).

tran3-l-Chloro-2-methoxycycloheptane

The method used to prepare trans-l-chloro-2-methoxycyclopentane

(vide supra) was followed exactly for the preparation of this compound,

with the exception that a smaller scale reaction was employed in the

present case, and the reaction was allowed to proceed four days.

Thus, cycloheptene (5.0 g), N-chlorosuccinimide (6.9 g) and 22 ml

39

of dry methanol were stirred at room temperature for 4 days.

Workup

(as reported above for the cyclopentyl analog) gave 4.5 g of the

crude product, which was ^^70% pure by GLPC analysis (Column E) .

A pure sample of the desired compound was isolated by preparative

GLPC (Column D operated at 200°C) and boiled at 99-101°/15 torr.

Anal. Calcd for CgH^^ClO: C, 59.07; H, 9.30.

Found: C, 59.33;

H, 9.27.

cis-1,2-Dichlorocycloalkanes

cis-1,2-Dichlorocyclopentane

The cis-dichloride was obtained from the corresponding epoxide

by reaction of 16.8 g of cyclopentene oxide and 78.7 g of triphenylphosphine in 100 ml of carbon tetrachloride, following the procedure

of Isaacs and Kirkpatrick.

53

Thus, the epoxide, triphenylphosphine,

and carbon tetrachloride were refluxed under nitrogen.

Periodically,

an aliquot of reaction mixture was removed, mixed with a small amount

of petroleum ether (30-60°), and examined for unconsumed epoxide

(GLPC, Column E ) . When no remaining starting material was observed

(2 hours), the mixture was allowed to cool, and was poured into

250-500 ml of 30-60° petroleum ether.

The supernant liquid was

decanted, the residual brown solid was ground (in portions) in a

mortar and pestle with some of the petroleum ether solution until

only light tan triphenylphosphine oxide crystals and the yellow

petroleum ether solution remained.

The solution was filtered to

remove the crystals, and the petroleum ether was evaporated under

40

reduced pressure to give the crude product. Distillation gave an

80% yield

of the desired compound, which was shown to be >98%

pure by GLPC (Column A operated at 72°C).

cis-1,2-Dichlorocyclohexane

A sample of this compound was available from previous work.

Purity was ascertained to be >99% by GLPC (Column A operated at 72°C).

cis-1,2-Dichlorocycloheptane

The title compound was prepared by the procedure

described

in detail for the cyclopentyl analog (vide supra) , with 0.2 mole

of cycloheptene being substituted for the cyclopentene.

was found to be complete after 3 days.

70°/l.l torr,

Reaction

The compound boiled at

was obtained in 80% yield, and was shown to be

99% pure by GLPC (Column A operated at 100°C).

cis-1,2-Dichlorocyclooctane

The cis-dichloride was prepared by the identical procedure

employed in the preparation of cis-1,2-dichlorocyclopentane (h scale),

with cyclooctene replacing cyclopentene.

after two days.

The reaction was stopped

Following a careful distillation to remove a trace

of the unconsumed epoxide, a 74% yield of the cis-dichloride was

56

obtained (bp 80-81°/0.8 torr. Lit.

bp 74°/l torr), which was shown

to be >95% pure by GLPC (Column A operated at 115°C).

cis-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane

cis-Epoxycyclododecane:

The peracid epoxidation of cis-cyclo-

dodecene (see trans-1,2-dichlorocyclododecane for the synthetic

method) was accomplished using the method of Nozaki and Noyori.45

41

Thus, 9.0 g of the cis-alkene in 16 ml of methylene chloride was

added dropwise to 5.5 g of m-chloroperbenzoic acid in 66 ml of

methylene chloride at 25°C.

Following the addition, the reaction

was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. The reaction

mixture was washed (10% Na2S02, 5% NaHCO^, dilute aq. NaCl, saturated

aq. NaCl) and dried (Na2S0^).

Distillation gave 5.5 g (bp 90-93°/

45

0.6 torr. Lit.

bp 88-90°/1.5 torr) of the desired product, which

was shown to be pure by capillary GLPC (Column E).

The IR spectrum

of the compound was identical to that previously reported.

cis-1,2-Dichlorocyclododecane:

from cis-epoxycyclododecane

The title compound was prepared

by the identical procedure employed

for the preparation of cis-1,2-dichlorocyclopentane (vide supra),

with the exception that a smaller scale was employed.

Thus, 5.5 g

of the epoxide, 11.9 g of triphenylphosphine, and 50 ml of carbon

tetrachloride were refluxed for 5 days, followed by the workup specified above for cis-1,2-dichlorocyclopentane.

A careful fractional

distillation of the 6.5 g of crude material gave a 70% yield of the

desired cis-dichloride [bp 145-147°/2.5 torr. Lit.

bp (mixture

with the trans isomer) 101°/1 torr].

11.12-Dichloro-9,10-dihydro-9,10ethanoanthracenes

trans-ll,12-Dichloro-9,10-dihydro9 ^10-ethanoanthracene

27 38

A sample of this compound, prepared previously by Lee, * was

available for utilization in the present research.

42

cis-11,12-Dichloro-9.10-dihydro9,10-ethanoanthracene

Treatment of anthracene with cis-1,2-dichloroethylene (Columbia

Organics) at 200°C for 24 hours in a sealed tube according to the

method of Cristol and Hause

27

gave the desired cycloaddition adduct.

Thus, 1.67 g of anthracene and 8.33 g of cis-1,2-dichloroethylene

were placed in each of three 26 mm X 200 mm thick-walled glass tubes,

which were sealed and heated for 24 hours at 200°C. Workup (according

to the published procedure

(10%) with anthracene.

27

) gave the desired compound, contaminated

Following repeated recrystallizations (CCl.)

a product was obtained (4.0 g) which was 95% pure by capillary GLPC

(Column E) and melted at 203° (Lit.^^ mp 203-204°C).

trans-2-Chipro-1-cyclohexyl Phenyl

Sulfide and Sulfone

trans-2-Chloro-1-cyclohexyl Phenyl

Sulfide

Treatment of cyclohexene (5.2 g) with a solution of phenylsulfenyl chloride (0.060 mole) in 60 ml of methylene chloride

according to the procedure (1/lOth scale) of Hopkins and Fuchs

afforded the title sulfide.

60

The crude product oil (14.1 g) , which

had been subjected to high vacuum to remove the residual solvent

gave a

H NMR spectrum which was identical to that published for

A 60

the compound.

trans-2-Chloro-l-cyclohexyl Phenyl Sulfone

Oxidation of the corresponding sulfide with m-chloroperbenzoic

60

acid according to the published procedure,

at six times the scale

43

of the published report, gave essentially a quantitative yield of

the crude sulfone, which was contaminated with 16% of 1-cyclohexen1-yl phenyl sulfone (capillary GLPC, Column E).

Careful recrystal-

lization of the crude product (hexane) gave a white solid with a H

NMR spectrum identical to the reported spectrum.

Miscellaneous Elimination Substrates

trans-l-Chloro-2-tosyloxycyclohexane

38

Lee

had previously prepared this sample. This material was

utilized following a check of the purity (97% by capillary GLPC,

Column E).

trans-[(2-Chlorocyclohexyl)oxy]trimethylsilane

trans-2-Chlorocyclohexanol:

The chlorohydrin was prepared in

82% yield by passing dry HCl into a solution of 50 g of cyclohexene

oxide in 50 ml of carbon tetrachloride until the solution was saturated, employing the procedure of Roberts and Hendrickson.

product chlorohydrin (bp 88-89°/10 torr. Lit.

The

bp 70-71°/7 torr)

was shown to be >99% pure by capillary gas chromatography (Column E).

trans-[(2-Chlorocyclohexyl)oxy]trimethylsilane:

Trimethyl-

silylation of the corresponding chlorohydrin with hexamethyldisilazane and a catalytic portion of concentrated sulfuric acid gave

the title compound in quantitative yield.

Thus, 5.0 g of the chloro-

hydrin, 3.6 g of hexamethyldisilazane, and 3 drops of concentrated

H SO

were stirred at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by

heating at 50°C for an additional hour.

After a 30 minute reflux

44

period, the reaction mixture was distilled under reduced pressure to

give a quantitative yield of the desired product with bp 105-106°/

8 torr.

Purity of the distilled product was determined to be >95%

by capillary gas chromatography (Column E).

The

H NMR spectrum

of the compound showed the following peaks:

6: 0.13 (s, 9H) ;

1.0-2.2 (n, 8H); 3.6 (n, 2H). Anal. Calcd for C H^^ClOSi: C,

52.27; H, 9.26.

Found:

C, 52.18; H, 9.28.

trans-2,3-Dichlorotetrahydropyran

The desired compound was prepared from 5-chloro-3,4-dihydro211-pyran (vide infra) by addition of anhydrous HCl to a benzene

solution of the starting material according to the procedure of

Stone and Daves.

Thus 1.2 g of the monochlorodihydropyran in

160 ml of dry benzene was treated with anhydrous HCl until the solution appeared to be saturated.

Following workup and evaporation

of the solvent, a quantitative yield of the desired material was

obtained.

The proton NMR spectrum of the product was in agreement

with that previously published.

62

The product was shown to be 99%

pure by capillary GLPC (Column E).

(E)-1,2-Dichloro-l-methylcyclohexane

The title compound was prepared by the chlorination of 1-methyl63

cyclohexene according to the procedure of Kharasch and Brown,

as previously employed by Hageman and Havinga.

64

Thus, to 8.0 g

of 1-methyl-l-cyclohexene, 8.0 g carbon tetrachloride, and 0.1 g

of azobisisobutyronitrile was added dropwise 10.8 g of sulfuryl

chloride in 8.0 g of carbon tetrachloride.

A one hour reflux period.

45

followed by distillation gave 16.0 g of the crude product. Preparative gas chromatography (Column D at 180°C)of the fraction boiling

at 41-44°/2.5 torr (Lit.^^ bp 66-67°/10 torr) gave pure (E)-l,2dichloro-1-methylcyclohexane.

Preparation of Authentic

Samples of Elimination Products

1-Bromocycloalkenes

1-Bromocyclobutene

trans-l-Bromo-2-chlorocyclobutane was treated with NaNH^NaO-t^-Bu

in THF at room temperature and worked up according to the standard

complex base reaction procedure (vide infra).

The resulting solution

was subjected to preparative gas chromatography (Column F operated

at 60°C) to give the desired 1-bromocyclobutene (as one of the

products), which was identified by comparison of GLPC retention

times with those reported previously.

The sample was shown to

be >99% pure by analytical GLPC (Coluirn C operated at 60°C) .

1-Bromocyclopentene

40

A sample, prepared previously by another worker, was employed

in the current research, following a purity determination (>99%)

by GLPC (Column A operated at 72°C).

1-Bromocyclohexene

40

The compound had been previously prepared by Lee.

,

A sample

from this previous synthesis was utilized after redistillation

(bp 44°/8 torr. Lit. ^ bp 63.l-63.4°/21 torr).

46

1-Bromocycloheptene

In analogy to the preparation of 1-bromocyclobutene, transl-bromo-2-chlorocycloheptane was treated with complex base (NaNH^NaO-t^-Bu) in THF at room temperature for 1 hr, followed by the standard

workup (vide infra).

Preparative gas chromatography (Column D operated

at 100°C) gave pure 1-bromocycloheptene.

determination

A micro boiling point

gave material with bp 185-186°/amb (Lit.^^ bp 66.5-

67.5°/13 torr).

1-Bromocyclooctene

A previously prepared

38

sample of the title compound was available.

This sample of 1-bromocyclooctene was utilized following a purity

determination (>99%) by GLPC (Column A operated at 115°C).

1-Chlorocycloalkenes

1-Chlorocyclobutene

The title 1-chloroalkene was collected from the preparative

gas chromatographic separation of the reaction mixture from which

1-broraocyclobutene was recovered (vide supra).

Thus, the complex

base reaction of trans-1-bromo-2-chlorocyclobutane gave 1-chlorocyclobutene

(>997)

and 1-bromocyclobutene , which was shown to be pure

by GLPC (Column C operated at 60°C) and identified by comparison

of GLPC retention times.

65

1-Chlorocyclopentene

40

A sample prepared by Lee

was employed in the present research

after GLPC analysis (Column A operated at 72°C) showed the compound

to be >99% pure.

47

1-Chlorocyclohexene

Treatment of cyclohexanone (100 g) with freshly sublimed phosphorus pentachloride (200 g ) , followed by addition of water according

to the procedure of Baude and Coles

*

gave a 50% yield of the

pure compound, bp 137°-139°/680 torr (Lit.

bp 141-143°/amb).

The

H NMR spectrum was identical to the published spectrum.

1-Chlorocycloheptene

In analogy to the preparation of 1-chlorocyclobutene from