Radical Protestantism and doux commerce

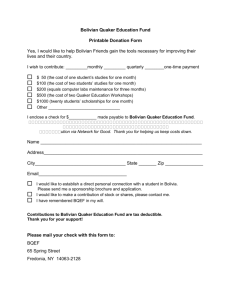

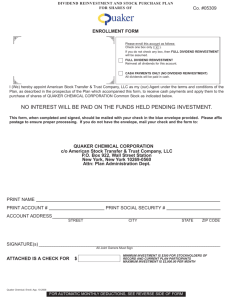

advertisement