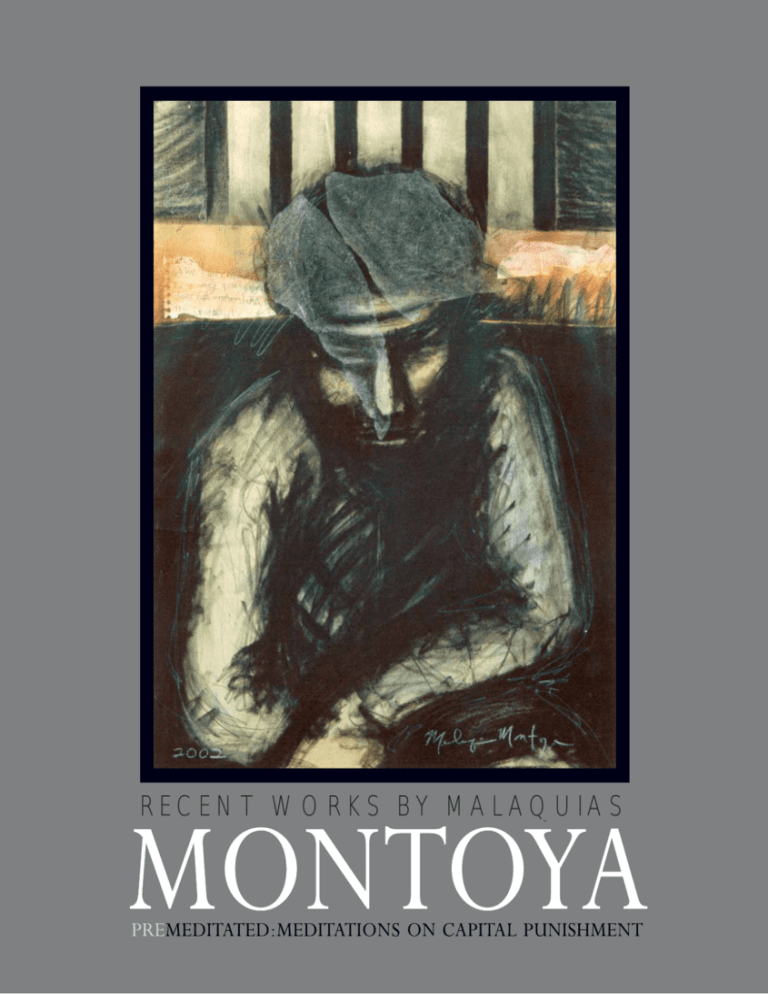

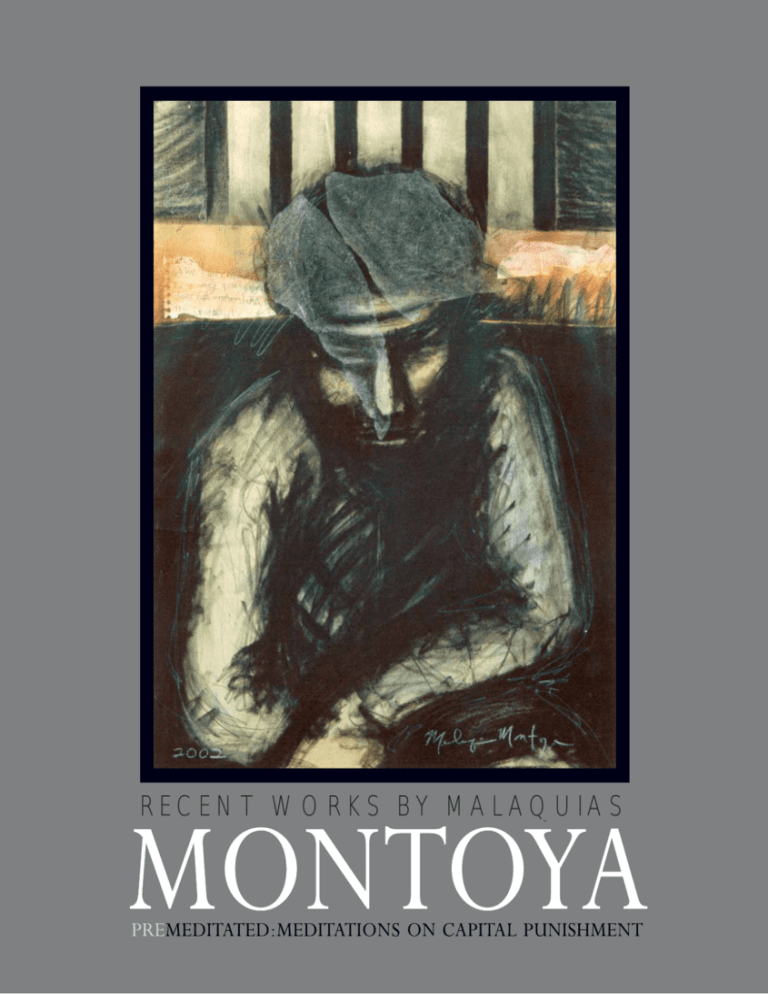

R E C E N T WO R K S B Y M A L AQU I A S

PREMEDITATED:

MEDITATIONS ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

R E C E N T W O R K S B Y M A L A Q U I A S M O N TOYA

An exhibition organized by the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame

For there to be equivalence, the death penalty would

have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim

of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death

on him and who, from that moment onward, had

confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster

is not encountered in private life.1

Albert Camus

3

Acknowledgments

Malaquias Montoya and Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya gratefully acknowledge the generous contributions

toward the publication of this catalogue. Major support has been provided by:

Institute for Latino Studies

Dr. Gilberto Cárdenas, Director

Caroline Domingo, Publications Manager

Snite Museum of Art

Charles Loving, Director

Gina Costa, Exhibit Curator

University of Notre Dame

The Center for Mexican American Studies

Dr. José E. Limón, Director

Dolores García, Assistant to the Director

University of Texas @ Austin

Chicana/o Studies Program

Dr. Adela de la Torre, Director

Committee on Research &

Office of the Deans

University of California, Davis

The Chicano Studies Research Center

Chon Noriega, Director

University of California, Los Angeles

Aztec America

Carlos Montoya, President & CEO

Chicago, Illinois

Ricardo and Harriet Romo

San Antonio,Texas

Special thanks to Carlos Jackson, MFA

University of California, Davis,

for the research conducted for this project

Design, photography, and research: Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya

Production: Jane Norton, Creative Solutions

Printing: Harmony Marketing Group

Co-published by Malaquias Montoya and Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya, and the Institute for Latino Studies,

University of Notre Dame.

For ordering information contact either of the addresses below:

Institute for Latino Studies

Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya

250F McKenna Hall

Post Office Box 6

University of Notre Dame

Elmira, CA 95625

Notre Dame, IN 46556

lsmontoya@earthlink.net

www.nd.edu/~latino/art

www.malaquiasmontoya.com

Cover image: The Killing of the Mentally Ill, 2002, Charcoal/Collage, 30x22 inches

© 2004 Malaquias Montoya and Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. No artwork from this book may be reproduced

in any form whatsoever without written permission from the publishers.

4

Introduction

in America, as realized through the creation of

a series of images depicting individuals being put to

death.These images challenged faculty and students

of Notre Dame, as indicated by their thoughts

shared in the exhibition comment book. One

student stated, “This exhibit struck me in

Montoya is deeply ideological in the leadership

a profound way. Indeed, our indifference to the

role he fills for the Chicano Art Movement; he

systematic execution of our fellow human beings

is iconoclastic, to American eyes, in his opposition

is a disturbing thing.” Another asked,

to capitalism and imperialism; he is

“Where are the pictures of the victims

humanistic in his opposition to

What concerns me

of those portrayed here?”

discrimination based on race, sex or

is, why do we kill,

class. Moreover, after lifelong

While Montoya promises to consider

devotion to “the cause,” he remains

what happens to

the plight of crime victims in future

profoundly idealistic.

our humanity and

work, this exhibition focuses on those

who are put to death as punishment for

Regardless of one’s politics, any thinking

to us, as a culture?

crimes they committed—or, possibly,

person has to admire an artist who has so

-Malaquias

Montoya

did not commit. As such, it features

selflessly “dedicated his life to informing

important historical references. The

and educating those neglected and

Electrocution of William Kemmler (2002, charcoal)

exploited peoples whose lives are at risk in milieus of

depicts the first person to be executed in the

racism, sexism, and cultural oppression.”2 In short, it

electric chair. The first attempt to kill Kemmler

is truly invigorating to find a contemporary artist

with a seventeen-second-charge of electric current

who shares this institution’s belief that art can be the

was a failure. The severely–burnt Kemmler was in

catalyst for positive change in individual lives.

agony throughout the time required to recharge the

chair. The second, successful attempt lasted over

For all of these reasons it was a pleasure and an

one minute, and several witnesses expressed

honor for the Snite Museum of Art, University of

revulsion at Kemmler’s moans of pain, the odor of

Notre Dame, to participate in the exhibition and

burning flesh and the smoke emanating from his

publication of Montoya’s most recent body

head. Ruth Snyder; First Woman Executed, Sing Sing

of work. We were especially grateful to be able

Prison, 1928 (2002, acrylic painting) depicts two

to prepare this exhibition since Montoya seldom

firsts. Not only was Snyder the first woman to be

ventures into the mainstream American art

executed in the electric chair, but a newspaper

system—namely, he does not produce his art

photographer who had smuggled a camera onto the

for the purpose of selling, he does not exhibit

scene documented the event. The following day a

in commercial galleries, and he is suspicious

photograph of the electrocution appeared on the

of museums.

front page of the Daily News. George Jackson Lives,

Murdered in 1971 by San Quentin Prison Guards (1976,

Premeditated: Meditations on Capital Punishment is the

offset lithograph) depicts the killing of this Black

artist’s prolonged consideration of the death penalty

Visual artist, poet and teacher, Malaquias Montoya

is one of an endangered species—a contemporary

artist who believes that art can make the world

a better place.

5

Panther, an event that was immortalized in Bob

Dylan’s song “George Jackson.” Mumia Abu-Jamal

(1999, charcoal/collage) celebrated a series of

public events that occurred on September 11,

1999, to protest the continued incarceration of

Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has been on death row

since 1982. Additional images depict more

generic executions, lynchings, and hangings.

The images are paintings, drawings, and silkscreen

prints. Some have collage elements; others

include texts from eyewitness accounts to

executions or statements made by journalists and

other writers. For example, Abolish the Death

Penalty (2000, silkscreen) includes the following

statement by Susan Blaustein, “We have perfected

the art of institutional killing to the degree that it

has deadened our natural, quintessentially human

response to death.” The images are either black

and white or they utilize strong, primary colors;

the strokes are expressionistic, aggressive and

gestural; drips suggest blood, vomitus, and other

body fluids.

In short, they are intentionally graphic—

effectively designed products of the graphic arts

and unpleasantly, vividly descriptive—designed

to shock us out of the indifference described in

Blaustein’s quote.

Finally, and so typical of Montoya, proceeds from

the sale of this catalog will benefit organizations

opposed to the death penalty.

Charles R. Loving

Director and Curator of Sculpture

Snite Museum of Art

University of Notre Dame

April 14, 2004

Numerous studies…report that the death penalty

has no deterrent effect.

6

Meditations on Capital Punishment

by Malaquias Montoya

though, conducted by various researchers, report

This project was conceived during the presidential

that the death penalty has no deterrent effect.7

election of 2000. There was a lot of media concentration on the state of Texas because our selected

president was governor there. A great deal of

What concerns me is: Why do we kill and what

attention was placed on the immense number

happens to us as a humanity, as a culture? Why is

of people being executed in that state’s death

state-sanctioned killing any different from a killing

chambers.3 I also started giving the death penalty

that takes place in the streets? One is planned and

the other is not? Amadou Diallo, shot forty-one

a lot of consideration when I did the poster design

times by the NYPD, had no weapon, was innocent,

for the Mumia 911 day.4 The possibility of this

and yet the police officers were set

brilliant man being murdered, on the

free.8 I personally remember the

basis of a flawed trial that left a lot of

We create the

uncertainty behind his conviction, was

young man, José Barlow Benavides,

situations that lead

hard to digest.5

shot to death by Peace Officer Cogley

in Oakland, CA.The investigation was

our children to

futile—no one was charged for the

I have always been against the death

commit monstrous

crime. One must ask oneself, who lives

penalty. It is an irrational idea that you

and who dies?

kill a person because s/he has killed

acts, and then we

another. It seems that the State,

kill them..

In August of 1945 the United States

composed of intelligent people, could

pulled off two incredible flybys

find another way of seeking justice;

awakening the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,

revenge seems too infantile a way of settling

killing and maiming hundreds of thousands of

a dilemma. So how does the victim obtain justice? In

civilians, forever changing the global perspective

a recent murder of a young woman and her unborn

of war and the balance of power. Eight years later,

child, the victim’s mother said, “she hopes that

afraid of losing that power, our government killed

whoever killed her daughter would hear her

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for alleged espionage.

daughter’s pleas not to be killed for as long as he

The sentencing judge stated, “By your betrayal, you

lives.”6 Life imprisonment without parole would

have undoubtedly altered the course of history to

allow this torment to continue. For proponents of

the disadvantage of our country.”9 Disadvantage? For

the death penalty, however, this punishment is too

easy; there is no immediate satisfaction; it is

years our government and its corporate backers

anticlimactic after a long and agonizing trial, which

have committed carnage against world citizens, and

kept us in daily suspense with headlines and TV

since World War II the great majority of these

news briefs. Death penalty proponents argue that

atrocities have been committed against people of

life imprisonment would not be enough admonition

color. South and Central America, the Caribbean,

to those preparing to murder; that those convicted

Asia, and the Middle East have all been playgrounds

must be killed in order to deter others from

for testing our latest “killing technology” and flexing

committing such heinous crimes. Numerous studies

our imperial power.

7

This insensitivity to human life not only takes

place on an international level but is also displayed

in our own country. Our communities—the poor

and people of color—are recipients of daily

violence. Dilapidated schools, crumbling buildings,

and service programs almost nonexistent due to

cutbacks are a type of violence committed on the

human psyche. Pain and violence are pervasive

throughout poor communities as drugs flourish

on street corners and police, ignorant and fearful,

perpetuate further terror. Mothers, fathers,

brothers and sisters are all walking around in

a state of shock waiting for the next violent act.

These poor communities are the victims of selfinflicted violence, and then to compound the

situation, they feel they are to blame, not the

greater structural mechanism. Our country’s

solution to all of this is to build more prisons and

increase the number on death row.10 This act of

concentrating the country’s poor into a cycle of

economic and physical violence seems to be

a purposeful act by the State. When billions and

billions of dollars are spent on war and we refuse

to educate our youth, house our homeless,

provide medical care to our elderly and ill, and

feed our hungry, one can only wonder what the

real intentions are. We create the situations that

lead our children to commit monstrous acts and

then we kill them.

We reap what we sow.

Amadou Diallo, shot forty-one times in 1999 by the NYPD, had

no weapon, was innocent, and yet the police officers were set free.

Amadou Diallo, 2001

Acrylic Painting

8

9

George Jackson, a member of the Black Panthers, was jailed with

a sentence of one year to life, ostensibly for stealing 70 dollars, and

later killed in a San Quentin prison riot in 1971. Many believe that

he was initially framed by the state in a racist response to his political

activism and subsequently murdered by prison guards because of his

attempts to organize his fellow inmates.

After Jackson’s death, prison officials charged six prisoners—the socalled San Quentin Six—in a 97-count indictment. Charges ranged

from attempted murder, conspiracy, escape, and assault to the killing

of the prison guards and inmates.

Their trial, at the time the longest in California history, lasted 17

months. Four days each week the six, shackled and chained, were led

into the Marin County Courthouse under heavy security. Eventually,

three were acquitted and three were convicted of lesser charges.11

George Jackson Lives, 1976

Offset Lithograph

10

11

Luis Talamantez is a human rights activist and artist who speaks

on the prison–industrial complex. A former political prisoner

(one of the San Quentin Six whose trial gained international

attention during the 1970s), Talamantez was acquitted and released

in 1976. Drawing on his experiences of 30 years behind bars, he

works to expose conditions at maximum security prisons like

California’s infamous Pelican Bay, Corcoran State Prison, and Valley

State Prison for Women. Talamantez is co-founder of California Prison

Focus and currently pens a column for their publication. He has

published two books of poetry and is an accomplished visual artist.12

Poem written and dedicated

to Malaquias Montoya

at the opening of his preview

exhibition at the Asian Resource

Gallery, Oakland, CA.

12

How time flies…

Our memories fade, and fall (on Silence)

The Silence of

Death Row—

is a “thing alone” never to forget,

—never to fall “Into”—

Inspiration

Reaches into the Dungeon Hole

Creativity Comforts our “Waiting,”

Our Silence

until—

the Final

Scream—

that Waits

inside us.

- Luis Talamantez, 2003

13

Mumia Abu-Jamal is an award-winning Pennsylvania journalist who

exposed police violence against minority communities. On death

row since 1982, he was wrongfully sentenced for the shooting

of a police officer. New evidence, including the recantation of a key

eyewitness, new ballistic and forensic evidence, and a confession from

Arnold Beverly (one of the two killers of Officer Faulkner) points

to his innocence. Mumia had no criminal record.

For the last 21 years Abu-Jamal has been locked up 23 hours

a day, been denied contact visits with his family, had his confidential

legal mail illegally opened by prison authorities, and been put into

punitive detention for writing his first of three books while in prison,

Live from Death Row.

His case is currently on appeal before the Federal District Court

in Philadelphia. Mumia’s fight for a new trial has won the support

of tens of thousands around the world. Mumia Abu-Jamal’s fate rests

with all those people who believe in every person’s right to justice

and a fair trial.5

Mumia Abu-Jamal, 1999

Charcoal/Collage

14

15

Lynching

During the heyday of lynching, between 1889 and 1918, 3,224

individuals were lynched, of whom 2,522 or 78 percent were Black.

Typically, the victims were hung or burned to death by mobs of

White vigilantes, frequently in front of thousands of spectators, many

of whom would take pieces of the dead person’s body as souvenirs

to help remember the spectacular event.13

Lynching Series 1, 2002

Charcoal

Overleaf:

Lynching Series 2, 2002

Silkscreen

Lynching Series 3, 2002

Silkscreen

16

17

18

19

No matter what anyone may say about vengeance or deterrence,

it is a matter of social control.14

- Joseph Ingle

The five countries with the highest homicide rates that do not

impose the death penalty average 21.6 murders per 100,000 people.

The five countries with the highest homicide rate that do impose

the death penalty average 41.6 murders for every 100,000 people.15

It’s a Matter of Social Control,

2002

Silkscreen

20

21

Hanging

Survival time: 8–13 minutes

After the hanging, the sentenced loses consciousness almost

immediately; the death occurs by asphyxiation, because of a slipknot

put around the neck and fixed to a support by the other end. The

weight of the body, hanging in mid-air or inclined forward, rests

on the slipknot, determines its closing and the compressing action

on respiratory tract. The hanging leaves different signs, both inside and

outside the body: the sentenced becomes cyanotic, the tongue hangs

out, the eyes pop out of his head, there is a groove on the neck;

there are also vertebral lesions and internal fractures.16 Three states,

Delaware, New Hampshire, and Washington, currently provide for

hanging as an option. Since 1977 three inmates have been executed

by hanging: two in Washington, and the last, in 1996, in Delaware.17

The Hanging Series 1, 2002

Charcoal/Pastel

Overleaf:

The Hanging Series 2, 2002

Silkscreen

The Hanging Series 3, 2002

Silkscreen

22

23

25

When in Gregg v. Georgia the Supreme Court gave its seal

of approval to capital punishment, this endorsement was premised

on the promise that capital punishment would be administered

with fairness and justice. Instead, the promise has become a cruel

and empty mockery. If not remedied, the scandalous state of our

present system of capital punishment will cast a pall of shame over

our society for years to come. We cannot let it continue.

- Justice Thurgood Marshall, 199018

Ruth Snyder, first woman

executed, Sing Sing Prison 1928,

2002 Acrylic Painting

26

27

Electrocution

In 1888 New York became the first state to adopt electrocution

as its method of execution. William Kemmler was the first man

executed by electrocution in 1890. Eventually twenty-six states

adopted electrocution as a “clean, efficient, and humane” means of

execution.Today, six states retain electrocution as their only method;

five others offer it as an option. It is the second most common

method of execution utilized in the modern era.19

The Electrocution

of William Kemmler, 2002

Charcoal

28

29

The Electrocution of William Kemmler

“Good-bye, William,” Durston said as he rapped

twice on the door.

Within the room, Davis sent the two-bell signal to

the dynamo room. The voltage was increased,

lighting the lamps on the control panel.Then Davis

pulled down the switch that placed the electric

chair into the circuit. The switch made

a noise that could be heard in the execution

chamber. Kemmler stiffened in the chair. The

plan had been to leave the current on for a full

20 seconds.

Dr. Spitzka, who had stationed himself next to

Kemmler in the room, watched Kemmler’s face

and hands. At first they turned deadly pale but

quickly changed to a dark red color.The fingers of

the hand seemed to grasp the chair. The index

finger of Kemmler’s right hand doubled up with

such strength that the nail cut through the palm.

There was a sudden convulsion as Kemmler strained

against the straps and his face twitched slightly, but

there was no sound from Kemmler’s lips.

“There is the culmination of ten years’ work and

study,” exclaimed Southwick. “We live in a higher

civilization from this day!”

Durston, however, insisted that the body was not

to be moved until the doctors signed the certificate

of death.

Dr. Balch, who was bending over the body looking

at the skin, noticed a rupture on the right index

finger of Kemmler’s right hand, where it had bent

back into the base of his thumb, causing a small cut,

which was dripping blood.

“Dr. MacDonald,” said Balch, “see the rupture?”

Dr. Spitzka held a stopwatch before him and

counted the seconds while examining Kemmler.

After just ten seconds had passed he shouted,

“Stop!” which was echoed by other people in the

room. Durston gave the order to the control

room, and Davis pulled the lever back, switching

the chair out of the circuit. The current had been

on for just 17 seconds.

Spitzka then gave the order, “Turn on the current!

Turn on the current instantly.This man is not dead!”

Kemmler’s body, which had been straining against

the straps, relaxed slightly when the current was

turned off.

This was not as easy as it might have been.When he

had been given the stop order, Davis had sent the

message to the control room to turn off the

dynamo. The voltmeter on the control panel was

almost back to zero. Davis is sent the two-bell

signal to the dynamo room and waited for the

current to build up again.

“He’s dead,” said Spitzka to Durston as the

witnesses who surrounded the chair congratulated

each other.

30

“Oh, he’s dead,” echoed Dr. MacDonald as the

other witnesses nodded in agreement. Spitzka

asked the other doctors to note the condition

of Kemmler’s nose, which had changed to a bright

red color. He then asked the attendants to loosen

the face harness so he could examine the nose

more closely. He then ordered that the body be

taken to the hospital.

Faces turned white, and the doctors fell back from

the chair. Durston, who had been next to the chair,

sprang back from the doorway and echoed

Spitzka’s order to “turn on the current.”

“Keep it on! Keep it on!” Durston ordered Davis.

The Human Experiment, 2003

Silkscreen

The group of witnesses stood by horror-stricken, their

eyes focused on Kemmler, as a frothy liquid began to drip

from his mouth. Then his chest began to heave and a heavy

sound like a groan came from his lips.Witnesses described

it as “a heavy sound,” as if Kemmler was struggling to

breathe. It continued at a regular interval, a wheezing

sound that escaped Kemmler’s tightly clenched lips.

Durston continued to shout to the control room to turn on

the current as some of the witnesses turned away from the

chair, unable to bear the sight of Kemmler. Quinby was so

sickened by the sight that he ran from the room. Another,

unidentified, witness lay down on the floor.20

31

Executions in the USA since 1976

Amnesty International USA21

Updated Mar 28, 2004

Year

Total

Executions

Cumulative

Total since 1976

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

1991

1990

1989

1988

1987

1986

1985

1984

1983

1982

1981

1980

1979

1978

1977

1976

18

65

71

66

85

98

68

74

45

56

31

38

31

14

23

16

11

25

18

18

21

5

2

1

0

2

0

1

0

903

885

820

749

683

598

500

432

358

313

257

226

188

157

143

120

104

93

68

50

32

11

6

4

3

3

1

1

0

Failed Electrocution, 2002

Charcoal

32

33

The Killing of the Innocent

“Marge, tell Mom not to bring any more cigarettes. My day

of execution has been set for Friday the 3rd. Tell Mother I will

soon be in the House of the Lord. He knows I am innocent.

Marge, don’t bring Mom.”

The Killing of the Innocent, 2002

Acrylic Painting

34

35

…Since we are guilty of no crime we will not be party to

the nefarious plot to bear false witness against other innocent

progressives to heighten hysteria in our land and worsen the

prospects of peace in the world…

…Nobody welcomes suffering, honey, but we are not the only

ones who are going through hell because of all we stand for

and I believe we are, in holding our own, contributing a share

in doing away with the great sufferings of many others, both

at this time and in time to come.

- Letter from Julius to Ethel Rosenberg, May 3, 195322

Executed, 2003

Silkscreen

36

37

The Gentle Sleep 1, 2002

Charcoal

Texas is the nation’s foremost executioner. It has been responsible for a third

of the executions in the country and has carried out two and a half times as

many death sentences as the next leading state. During the period when Texas

rose to become the nation’s leading death penalty state, its crime rate grew by

24 percent and its violent crime increased by 46 percent, much faster than the

national average.Texas leads the country in numbers of its police officers killed,

and more Texans die from gunshot wounds than from car accidents.23

38

The Gentle Sleep 2, 2002

Silkscreen

His head pointed up, his body lay flat and still for seconds. Then a harsh

rasping began. His fingers trembled up and down, and the witnesses standing

near his midsection say that his stomach heaved. Quiet returned, and his head

turned to the right, toward the black dividing rail. A second spasm of wheezing

began. It was brief. His body moved no more.24

39

Lethal Injection

When the IV tubes are in place, a curtain may be drawn back from

the window or one-way mirror to allow witnesses to view the

execution. At this time, the inmate is given a chance to make a final

statement, either written or verbal. This statement is recorded and

later released to the media. The prisoner’s head is left unrestrained —

in states that use regular windows, this enables the inmate to turn

and look at the witnesses. In states that use one-way mirrors, the

witnesses are shielded from view.25

A More Gentle Way of Killing...

2003

Silkscreen

40

41

By using medical knowledge and personnel to kill people, we do

more than undermine the emerging standards and procedures for

good, ethical decision-making about the sick and dying. We also

set off toward a terrifying land where the white gowns of physicians

are covered by the black hoods of executioners.26

The Executioner, 2003

Silkscreen

42

43

The Killing of the Mentally Ill

I remember very clearly the case of a mother watching her son

with mental retardation standing trial for his life. One could see she

had given a lot of thought to what she could do to comfort him,

or to make some connection with this son who had such a low

I.Q. Finally, the one thing she found to do all day was to give him

a small candy bar. That at least, was something he could understand

during his trial.27

The Killing of the Mentally Ill, 2002

Charcoal/Collage

44

45

We as a society are fed daily acts of violence. The legalized killing

of another human being seems to satisfy our violent and vengeful

impulses. We are becoming more grotesque than the most hideous

crimes—and we have allowed it to happen.

The Victim, 2003

Silkscreen

46

47

Racial minorities are being prosecuted under federal death penalty

law far beyond their proportion in the general population or the

population of criminal offenders. Analysis of prosecutions under

the federal death penalty provisions of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of

1988 reveals that 89 percent of the defendants selected for capital

prosecution have been either African-American or MexicanAmerican…race continues to play an unacceptable part in the

application of capital punishment in America today. 28

Racial discrimination pervades the US death penalty at every stage

of the process…There is only one way to eradicate ethnic bias, and

the echoes of racism, from death penalty procedures in the United

States—and this is by eradicating the death penalty itself.29

48

Abolish the Death Penalty, 2000

Silkscreen

We have perfected the art of institutional killing to the degree that

it has deadened our natural, quintessentially human response to death.30

49

50

Death Row Exonerations, 1973–2004

Between 1973 and February 2004, 113 inmates on

death row have been exonerated and freed.The most

common reasons for wrongful convictions are mistaken

eyewitness testimony, the false testimony of informants

and “incentivized witnesses,” incompetent lawyers,

defective or fraudulent scientific evidence, prosecutorial

and police misconduct, and false confessions. In recent

years, DNA played a role in overturning 12 of these

wrongful death row convictions.31

Exhibition Tour

Snite Museum of Art, Milly and Fritz Kaeser Mestrovic Studio Gallery, Notre Dame, IN. January11–February 22, 2004

Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, Chicago, IL. August 20–November 14, 2004

Julia C. Butridge Gallery, Dougherty Arts Center, Austin,TX. January 2005

Instituto Mexicano, San Antonio,TX. February 2005

Preview exhibition, Asian Resource Gallery, Oakland, CA. May–June, 2003

The exhibition tour will continue during the next several years.

Contact Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya: 707-447-4194 or lsmontoya@earthlink.net regarding new bookings,

tour schedules, and new venues.

Works in the Exhibition

Amadou Diallo, 2001

Acrylic Painting, 51x42 inches

The Human Experiment, 2003

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

George Jackson Lives, 1976

Offset Lithograph, 22x17.5 inches

Failed Electrocution, 2002

Charcoal, 24x18 inches

Mumia Abu-Jamal, 1999

Charcoal/Collage, 30x22 inches

The Killing of the Innocent, 2002

Acrylic Painting, 53x50 inches

Lynching Series 1, 2002

Charcoal, 24x18 inches

Executed, 2003

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

Lynching Series 2, 2002

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Gentle Sleep 1, 2002

Charcoal, 24x18 inches

Lynching Series 3, 2002

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Gentle Sleep 2, 2002

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

It’s a Matter of Social Control, 2002

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

A More Gentle Way of Killing..., 2003

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Hanging Series 1, 2002

Charcoal/Pastel 24x18 inches

The Executioner, 2003

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Hanging Series 2, 2002

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Killing of the Mentally Ill, 2002

Charcoal/Collage, 30x22 inches

The Hanging Series 3, 2002

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Victim, 2003

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

Ruth Snyder, first woman executed,

Sing Sing Prison 1928, 2002

Acrylic Painting, 55x51 inches

Abolish the Death Penalty, 2000

Silkscreen, 30x22 inches

The Electrocution of William Kemmler, 2002

Charcoal, 24x18 inches

52

Malaquias Montoya

Malaquias Montoya is a

leading figure in the

Chicano graphic arts

movement, a political and

socially conscious movement that expresses itself

primarily through the

mass production of silkscreened posters. Montoya’s works include acrylic

paintings, murals, washes, and drawings, but he is

primarily known for his silkscreen prints, which

have been exhibited both nationally and

internationally. He is credited by historians as being

one of the founders of the “social serigraphy”

movement in the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid1960s. His visual expressions, art of protest, depict

the struggle and strength of humanity and the

necessity to unite behind that struggle. Like that of

many Chicana/o artists of his generation, Montoya’s

art is rooted in the tradition of the Taller de Gráfica

Popular, the Mexican printmakers of the 1920s,

’30s and ’40s, whose work expressed the need for

social and political reform for the Mexican

underprivileged. Montoya’s work uses powerful

images, which are combined with text to create his

socially critical messages.

© Alan Pogue

Montoya was raised in a family of seven children in

the San Joaquin Valley, California, by parents who

could not read or write. His father and mother were

divorced when he was ten and his mother continued

to work in the fields to support the four children

still remaining at home so they could pursue their

education. Since 1968 he has lectured and taught

at numerous universities and colleges in the

San Francisco Bay Area, including Stanford and

the University of California, Berkeley. He was

a professor at the California College of Arts and

Crafts for twelve years, during five of which he was

chair of the Ethnic Studies Department. As director

of the Taller de Artes Gráficas in Oakland for five

years, he produced various prints and conducted

many community art workshops. Montoya,

a visiting professor in the Art Department at the

University of Notre Dame in 2000, continues as

a Visiting Fellow of the Institute for Latino Studies,

also at Notre Dame.

Since 1989 Montoya has been a professor at the

University of California, Davis. His classes, through

the Departments of Chicana/o Studies and Art,

include silkscreening, poster making, and mural

painting, and focus on Chicana/o culture and history.

This exhibition features recently created silkscreen

images and paintings and related text panels dealing

with the death penalty and penal institutions—

inspired by the escalation of deaths at the hands of

the State of Texas in recent years. Montoya has

created images so powerful, so disturbing,

so introspective, that viewers will not be able to

examine them and walk away without feeling that

they have witnessed an atrocity that has been

committed in their names. As Montoya states,

“I agree with journalist Susan Blaustein when she

says that ‘we have perfected the art of institutional

killing to the degree that it has deadened our

natural, quintessentially human, response to death.’

I want to produce a body of work depicting the

horror of this act.” In these works Montoya

illuminates the inhumanity of the horrendous act

of premeditated murder committed by the state—

a situation where the use of punishment to

discourage crime encourages criminality.

Gina Costa

Snite Museum of Art

53

References and Notes

1.

Albert Camus, Resistance, Rebellion, and Death (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1960), 199.

2.

Joseph Zirker, Malaquias Montoya (San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Art Institute, 1977), 10.

3

Tom Brune, “Convention 2000 / The Republicans / George W. Bush’s Texas / Strong Backer of Death Penalty,” Newsday,

August 3, 2000 (Washington Bureau, HighBeam™ Research, LLC).

http://www.highbeam.com/library/doc0.asp?docid=1P1:30361052&refid=ink_d6&skeyword=&teaser=

Texas Moratorium Network (TMN), an all-volunteer, grassroots organization formed in August 2000 with the primary goal

of mobilizing statewide support for a moratorium on executions in Texas. http://texasmoratorium.org/?group=5

Death Penalty Information Center, 1320 18th Street NW, 5th Floor,Washington DC 20036.

http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/

54

4.

MUMIA 911:The Artists Network helped launch and organize the National Day of Art to Stop the Execution of Mumia

Abu-Jamal, held on September 11, 1999, 305 Madison Ave. #1166, New York City, NY 10165.

http://www.artistsnetwork.org/mumia/mumia911.html

5.

The Mobilization to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal, 298 Valencia St., San Francisco, CA 94103, 415-255-1085.

http://www.freemumia.org/

6.

Cynthia McFadden, Mike Gudgell, Steffan Tubbs, and Taina Hernandez, contributors, “‘I Am Not Guilty’ Scott Peterson

Pleads Not Guilty; Laci Peterson’s Family Vows Justice,” April 21, 2004, ABC News.

http://abcnews.go.com/sections/us/SciTech/laci030421.html

7.

Hugo Adam Bedau, The Case against the Death Penalty (Washington, DC: Death Penalty Information Center and the American

Civil Liberties Union OnLine Archives, copyright 1997, in English and Spanish).

http://archive.aclu.org/library/case_against_death.html

8.

Frank Serpico, “Diallo Speaks to Serpico, Amadou’s Ghost,” The Village Voice, Features, March 8–14, 2000.

http://www.villagevoice.com/issues/0010/serpico.php

9.

Walter & Miriam Schneir, Invitation to an Inquest (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company Inc., 1965), 1.

10.

Eve Goldberg and Linda Evans, “The Prison-Industrial Complex and the Global Economy,” posted at globalresearch.ca,

October 18, 2001. http://globalresearch.ca/articles/EVA110A.html

11.

Walter Rodney, “George Jackson: Black Revolutionary,” World History Archives, November 1971.

http:// www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/index-beb.html

12.

SPEAKOUT! Institute for Democratic Education and Culture, PO Box 99096, Emeryville, CA 94662, 510-601-0182.

http://www.speakersandartists.org/

13.

Richard M. Perloff, “The Untold, Forgotten Story of the Press and the Lynching of African Americans,” Department

of Communication, Cleveland State University, February 17, 2000.

http://www.csuohio.edu/clevelandstater/Archives/Vol 1/Issue 13/news/news2.html

14.

Joseph Ingle, The Machinery of Death, a Shocking Indictment of Capital Punishment in the United States (New York: Amnesty

International USA, 1995), 114.

15.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP), “The Death Penalty Has No Beneficial Effect on Murder Rates,”

Fact Sheet: Deterrence. http://www.ncadp.org/fact_sheet5.html

16.

The Oracle Education Foundation, a California not-for-profit corporation, “When Life Generates Death (Legally),”

ThinkQuest: Death Penalty. http://library.thinkquest.org/23685/data/hanging.html

17.

Florida Corrections Commission, 725 South Calhoun Street, Suite 109 Bloxham Building,Tallahassee, FL 32301.

http://www.fcc.state.fl.us/

18.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, speech delivered at the 1990 annual dinner in honor of the judiciary, American Bar

Association, and quoted in the National Law Journal, Feb. 8, 1993. www.deathpenaltyinfo.org.

19.

Florida Corrections Commission. http://www.fcc.state.fl.us/

20.

Craig Brandon, The Electric Chair, an Unnatural American History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company

Inc. Publishers, 1999), 176–77.

21.

Amnesty International USA, 322 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10001, “Executions in the USA since 76.”

http://www.amnestyusa.org/abolish/listbyyear.do

22.

Walter and Miriam Schneir, Invitation to an Inquest, 233.

23.

Richard C. Dieter, “The Future of the Death Penalty in the US: A Texas-Sized Crisis,” Death Penalty Information

Center, May 1994. http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?scid=45&did=489

24.

Amnesty International USA, “According to Witnesses...” http://www.amnestyusa.org/abolish

25.

Kevin Bonsor, “How Lethal Injection Works.” http://people.howstuffworks.com/lethal-injection.htm

26.

Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Who Owns Death? Capital Punishment, the American Conscience, and the End of

Executions (New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.), 96.

27.

Ronald W. Conley, Ruth Luckasson, and George N. Bouthilet, The Criminal Justice System and Mental Retardation:

Defendants and Victims (Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., 1992).

28.

Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights Committee on the Judiciary, “Racial Disparities in Federal Death

Penalty Prosecutions 1988-1994,” Staff Report, One Hundred Third Congress, Second Session, March 1994.

http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?scid=45&did=528

29.

Amnesty International, “Killing with Prejudice: Race and the Death Penalty in the USA,” May 1999.

Quoted at http://www.amnestyusa.org/abolish/racialprejudices.html

30.

Susan Blaustein, “Witness to Another Execution,” Harpers Magazine, May 1994, p. 53.

31.

Alan Gell, “Death Row Exonerations, 1973–2004,” latest release recorded Feb. 18, 2004.

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0908211/html

An electronic version of this catalogue, with live links, can be viewed online at www.malaquiasmontoya.com and

www.nd.edu/~latino/art.

55

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this catalogue will go to the following

organizations actively working to abolish the death penalty.

THE NATIONAL COALITION TO ABOLISH THE DEATH PENALTY provides information, advocates for public policy, and mobilizes and supports individuals and institutions that share our unconditional rejection of capital punishment. Our commitment to abolition of the death penalty is rooted in several critical concerns. First and foremost, the death penalty devalues all human life—eliminating the possibility for transformation of spirit that is intrinsic to humanity. Secondly, the death penalty is fallible and

irrevocable—over one hundred people have been released from death row on grounds of innocence in

this “modern era” of capital punishment.Thirdly, the death penalty continues to be tainted with race and

class bias. It is overwhelming a punishment reserved for the poor (95 percent of the over 3,700 people

under death sentence could not afford a private attorney) and for racial minorities (55 percent are people of color). Finally, the death penalty is a violation of our most fundamental human rights—indeed, the

United States is the only western democracy that still uses the death penalty as a form of punishment.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

920 Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E.

Washington, D.C. 20003

202-543-9577

www.ncadp.org

CITIZENS UNITED AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY works to end the death penalty in the United

States through aggressive campaigns of public education, and the promotion of tactical grassroots activism.

Invigorated education involves the use of mass media to effectively communicate to the US public the

message that the death penalty is bad public policy on economic, moral, and social grounds. To effect

political change, alternatives to the death penalty must be made attractive to the majority of US voters.

Mass public education must be reinforced at the grassroots level by local organizations and respected individuals. Politicians must be provided the support to lead on this issue, even in the face of unpopular public sentiment. CUADP is committed to act as a catalyst for continued development and implementation

of a national grassroots strategy.

Citizens United for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

PMB 335

2603 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Hwy

Gainesville, FL 32609

800-973-6548

cuadp@cuadp.org

JOURNEY OF HOPE...FROM VIOLENCE TO HEALING is an organization led by murder victim

family members that conducts public education speaking tours and addresses alternatives to the death

penalty. Journey “storytellers” come from all walks of life and represent the full spectrum and diversity

of faith, color and economic situation. They are real people who know first hand the aftermath of the

insanity and horror of murder.They recount their tragedies and their struggles to heal as a way of opening dialogue on the death penalty in schools, colleges, churches, and other venues.The Journey spotlights

murder victims’ family members who choose not to seek revenge and instead select the path of love and

compassion for all of humanity. Forgiveness is seen as a strength and as a way of healing. The greatest

resources of the Journey are the people who are a part of it.

Journey of Hope…From Violence to Healing, Inc.

PO Box 210390

Anchorage,AK 99521-0390

877-9-24GIVE (4483)

http://www.journeyofhope.org/

56

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this catalogue will go

to organizations actively working to abolish the death penalty.