1 Why the Working Class? - Socialist Workers Party

advertisement

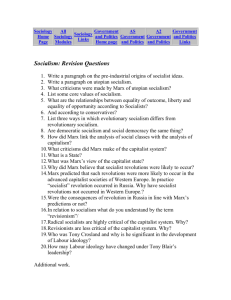

Education For Socialists 1 Why the Working Class? 2 Education for Socialists The Workers’ Vital Role Duncan Hallas 3-5 The Two Souls of Socialism Hal Draper 6-9 Class and Revolution Chris Harman 10-20 The Shape of the Working Class Martin Smith 21-31 Why the Working Class? 3 The Workers’ Vital role Duncan Hallas First printed in The Meaning of Marxism (1971) “A development of the productive forces is the absolute practical premise of communism because without it want is generalised, and that means that all the old crap must revive again.” By “all the old crap” Marx meant classes, inequality, class struggles and war. On a world scale this problem has been solved. The material basis for socialism exists, but as a result of the course of capitalist development it is very unevenly distributed. For example, in the USA output per man-hour, averaged for all sectors of the economy, rose from 37 units in 1870 to 100 units in 1913 (taken as baseline), to 208 units in 1938 and to nearly 400 units in 1963. On the other hand, in most of the “underdeveloped” countries overall productivity remains very low. It has been kept low by the competitive power of the developed capitalist countries and by the transfer of resources from the “underdeveloped” to the “developed” by imperialism. A Chinese economist published a book in 1950 giving these figures: “In the USA there was an average of about 600 times more industrial capital per head (of the population) than in China, or more than 900 times if manufacturing capital alone were considered.” Even making every allowance for industrial development since 1950 it is clear that the basis for a classless society in an isolated 4 Education for Socialists China does not exist.1 The same argument applies to the rest of the “Third World”, that is, to two-thirds of mankind. What does exist is the possibility of an international socialism and this requires the growth of an international revolutionary movement. Such a movement must be based on the industrial working classes. This is not a question of dogma. It is fundamental to the Marxist analysis of society and follows from the actual life situation of the modern workers as compared to that of all previous exploited classes. While it is the case that the low level of the productivity of labour was the basic reason for inequality and exploitation in ­pre‑capitalist societies there was also another reason. In pre-industrialised societies the working people, whether slaves, serfs or “free” peasants, normally worked in fairly small groups isolated from similar groups widely scattered over the countryside. This made it very difficult for them to think in collective terms and still more difficult for them to act as a class. As Marx, writing of the French peasantry, noted, “Insofar as millions of families live under economic conditions of existence that divide their mode of life...from that of other classes, and put them in hostile contrast to the latter, they form a class. Insofar as there is merely a local interconnection among these small peasants, and the identity of their interests, begets no unity, no national union, and no political organisation, they do not form a class. They are consequently incapable of enforcing their class interests... They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented.” Slaves, serfs, peasants could and often did revolt, burn the big houses and kill lords, priests and lawyers. What they could not do, except for short periods in exceptional circumstances, was impose their rule, as a class, on society. Either the old rulers regained control or others took their place. For the cultivators had sooner or later to disperse to their plots or starve. Professional rulers arose to “represent” them. 1:The expansion of the Chinese industrial production since this article ­partially invalidates this argument, though it remains the case that the mass of China’s population languishes in poverty. Hallas’s point certainly does still hold true across most of the Global South—editor’s note. Why the Working Class? 5 It is the concentration of the modern working class into large units in cities and the enormous development of means of communication that makes possible trade union and political organisation. They make it possible for the working class, the great majority, to impose its collective will on society. There is no possible substitute. Socialism means a society based on voluntary cooperation between working people. It can neither be established in the absence of a modern working class nor imposed on one from above. Marx took as his model of working class rule the Paris Commune of 1871. His description of its working is still, in essentials, the outline of a “workers’ state”, though the rise of large-scale industry has made workers’ councils based on productive units more important than area organisation. The Commune was formed of municipal councillors chosen by universal suffrage...responsible and recallable at short terms. The majority of its members were naturally working men... The Commune was to be a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time...the police was at once stripped of its political attributes and turned into the responsible and at all times recallable agent of the Commune. So were the officials of all other branches of the administration. From the members of the Commune downwards, the public service had to be done at workmen’s wages. The vested interests and allowances of the high dignitaries disappeared along with the high dignitaries themselves... Like the rest of public servants, magistrates and judges were to be elective, responsible and recallable... The first decree of the Commune was the abolition of the standing army and the substitution for it of the armed people. Such a revolutionary and democratic regime, solidly based on the working class, is the essential instrument for the transition to socialism. To establish it, of course, the capitalist state machine must be eliminated because workers’ power is incompatible with any kind of bureaucratic and repressive hierarchy. 6 Education for Socialists The Two Souls of Socialism Hal Draper An extract from the classic pamphlet (1966) The nearest thing to a common content of the various ­“socialisms” is a negative: anti-capitalism. On the positive side, the range of conflicting and incompatible ideas that call themselves socialist is wider than the spread of ideas within the bourgeois world. Even anti-capitalism holds less and less as a common factor. In one part of the spectrum, a number of social democratic parties have virtually eliminated any specifically socialist demands from their programmes, promising to maintain private enterprise wherever possible. In another part of the world picture, there are the Communist states, whose claim to being “socialist” is based on a negative: the abolition of the capitalist private-profit system. However, the socio‑economic system which has replaced capitalism there would not be recognisable to Karl Marx.1 The state owns the means of production—but who “owns” the state? Certainly not the mass of workers, who are exploited, unfree, and alienated from all levers of social and political control. These two self-styled socialisms are very different, but they have more in common than they think. The social democracy has typically dreamed of “socialising” capitalism from above. Its principle 1: Hal Draper saw the Stalinist states as a new form of class society, whereas for the SWP saw them as examples of state capitalism. This, in fact, adds weight Draper’s critique. See Tony Cliff ’s Trotskyism After Trotsky (available from www.marxists.org) for more details—editor’s note. Why the Working Class? 7 has always been that increased state intervention in society and economy is per se socialistic. It bears a fatal family resemblance to the Stalinist conception of imposing something called socialism from the top down, and of equating statification with socialism. Both have their roots in the ambiguous history of the socialist idea. There have always been different “kinds of socialism”, and they have customarily been divided into reformist or revolutionary, peaceful or violent, democratic or authoritarian, etc. These divisions exist, but the underlying division is something else. Throughout the history of socialist movements and ideas, the fundamental divide is between Socialism-from-Above and Socialism-from-Below. What unites the many different forms of Socialism-from-Above is the conception that socialism (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) must be handed down to the grateful masses in one form or another, by a ruling elite which is not subject to their control in fact. The heart of Socialism-from-Below is its view that socialism can be realised only through the self-emancipation of activised masses in motion, reaching out for freedom with their own hands, mobilised “from below” in a struggle to take charge of their own destiny, as actors (not merely subjects) on the stage of history. “The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves”: this is the first sentence in the Rules written for the First International by Marx, and this is the First Principle of his lifework. What Marx did In the socialist movement as it developed before Marx, nowhere did the line of the Socialist Idea intersect the line of ­Democracy‑from­­‑Below. This intersection, this synthesis, was the great contribution of Marx: in comparison, the whole content of his Capital is secondary. This is the heart of Marxism: “This is the Law; all the rest is commentary.” The Communist Manifesto of 1848 marked the self-consciousness of the first movement (in Engels’s words) “whose notion was from the very beginning that the emancipation of the working class must be the act of the working class itself ”. The young Marx himself went through the more primitive stage just as the human embryo goes through the gill stage; or to put it 8 Education for Socialists differently, one of his first immunisations was achieved by catching the most pervasive disease of all, the illusion of the Saviour-Despot. When he was 22, the old kaiser died, and to the hosannas of the liberals Friedrich Wilhelm IV acceded to the throne amidst expectations of democratic reforms from above. Nothing of the sort happened. Marx never went back to this notion. Marx entered politics as the crusading editor of a newspaper which was the organ of the extreme left of the liberal democracy of the industrialised Rhineland, and soon became the foremost editorial voice of complete political democracy in Germany. The first article he published was a polemic in favour of the unqualified freedom of the press from all censorship by the state. By the time the imperial government forced his dismissal, he was turning to find out more about the new socialist ideas coming from France. When this leading spokesman of liberal democracy became a socialist, he still regarded the task as the championing of democracy—except that democracy now had a deeper meaning. Marx was the first socialist thinker and leader who came to socialism through the struggle for liberal democracy. In working out the viewpoint which first wedded the new communist idea to the new democratic aspirations, they came into conflict with the existing communist sects such as that of Weitling, who dreamed of a messianic dictatorship. Before they joined the group which became the Communist League (for which they were to write the Communist Manifesto), they stipulated that the organisation be changed from an elite conspiracy of the old type into an open propaganda group, that “everything conducive to superstitious authoritarianism be struck out of the rules”, that the leading committee be elected by the whole membership as against the tradition of “decisions from above”. When the Communist League split, it was in conflict once again with the “crude communism” of putschism, which thought to substitute determined bands of revolutionaries for the real mass movement of an enlightened working class. Marx told them: The minority...makes mere will the motive force of the revolution, instead of actual relations. Whereas we say to the workers, Why the Working Class? 9 “You will have to go through 15 or 20 or 50 years of civil wars and international wars, not only in order to change extant conditions, but also in order to change yourselves and to render yourselves fit for political dominion,” you, on the other hand, say to the workers, “We must attain to power at once, or else we may just as well go to sleep.” In order to change yourselves and to render yourselves fit for political dominion: this is Marx’s programme for the working class movement, as against both those who say the workers can take power any Sunday, and those who say never. Marxism came into being, in ­self‑conscious struggle against the advocates of the Educational Dictatorship, the Saviour-Dictators, the revolutionary elitists, the communist authoritarians, as well as the philanthropic do-gooders and bourgeois liberals. The heart of the theory is this proposition: that there is a social majority which has the interest and motivation to change the system, and that the aim of socialism can be the education and mobilisation of this mass-majority. This is the exploited class, the working class, from which comes the eventual motive-force of revolution. Hence a Socialism-from-Below is possible, on the basis of a theory which sees the revolutionary potentialities in the broad masses, even if they seem backward at a given time and place. Capital, after all, is nothing but the demonstration of the economic basis of this proposition. It is only some such theory of working class socialism which makes possible the fusion of revolutionary socialism and revolutionary democracy. We are not arguing at this point our conviction that this faith is justified, but only insisting on the alternative: all socialists or would-be reformers who repudiate it must go over to some Socialism-from-Above, whether of the reformist, utopian, bureaucratic, Stalinist, Maoist or Castroite variety. And they do. Five years before the Communist Manifesto a freshly converted 23-year-old socialist had still written in the old elitist tradition, “We can recruit our ranks from those classes only which have enjoyed a pretty good education; that is, from the universities and from the commercial class.” The young Engels learned better; but this obsolete wisdom is still with us as ever. 10 Education for Socialists Class and Revolution Chris Harman From Revolution in the 21st Century (Bookmarks, 2007) Revolutionary socialists believe the working class is the key to transforming society. This follows from the character of capitalist society. Capitalists cannot survive without making profits, but they cannot do that without bringing workers together to exploit and thus creating discontent. This is what Marx meant when he wrote that capitalism creates its own “gravedigger”. Ruling classes before capitalism also exploited the mass of the population. But they did so mainly by exploiting peasants dispersed across the countryside, each family tending its own land, living in villages or hamlets with little connection between them, speaking localised dialects unable to read and write, and possessing little understanding of the wider world. Capitalism, by contrast, concentrates those it exploits in giant cities in workplaces where improved conditions can only be obtained through collective struggle. In order to exploit workers to the maximum, capitalists demand a level of literacy and numeracy higher than that among most of the exploiting classes of the past. In doing so the system creates a class with the capacity to organise against it and the potential to turn society on its head. The reality of class today The revolutionary movements of the 20th century were centred on the industrial working class. Innumerable academics and media Why the Working Class? 11 pundits argue this makes workers irrelevant to the question of revolution today because the working class has declined as a force. If there is talk of demands for change it is couched in terms of ­“multitudes” and “social movements”. There is no doubt the proportion of people employed in manufacturing and mining has declined in Britain and certain other advanced industrial countries. The number in manufacturing in Britain today is about half that of 1973. But this does not mean the industrial working class has disappeared—its numbers were still growing in the US until only six years ago and even in Britain there are still millions of such workers. More importantly, the notion of the working class cannot be restricted to those in particular industries. The media, politicians and academics treat class as a question of lifestyles or, following the German sociologist Max Weber, “life chances”. Their starting point is the way people dress and speak, the character of the jobs they do, the degree to which they are held in esteem or the extent to which they live in poverty. This leads to the assertion that we live in an increasingly middle class society, since the proportion doing heavy manual work has declined while increasing numbers work in white-collar, service sector jobs. We live in a “two‑thirds, one-third” society, it is claimed, in which most people prosper and a minority make up an “underclass”. Many on the left see class in similar ways—identifying a “labour aristocracy” of skilled, male manual workers and an impoverished underclass, or portraying industrial manual workers at “proletarian” and white-collar and service sector workers as middle class. These theories obscure the fact that the fundamental divide in society is between those who control the means of production and those who work for them. Lifestyle, dress, income and consumption are products of this division, not its cause. It is irrelevant if occasional members of the possessing class choose to slum it, or if some of the toilers gain marginal advantages and imitate aspects of the lifestyle of their exploiters. The fact that the head of Barclays and a counter clerk in a branch of the bank both wear suits does not bridge the gap between them. The bank clerk, ­computer 12 Education for Socialists ­ perator and call centre employee are compelled to accept o ­voluntary ­wage-slavery, five days a week, 48 weeks a year, just as much as a car worker or docker. Restructuring and the continuity of class The competition at the core of capitalism means that firms repeatedly restructure production to try to get ahead of rivals and to survive recurrent crises. This leads to the repeated restructuring of the labour force. Some groups of workers diminish in size and others expand. So in Britain in the 1830s and 1840s the biggest concentrations of workers were in textiles. When people thought of the typical worker, they thought of someone in a cotton mill. Forty years later, whole new branches of industry were expanding and people increasingly identified the working class with those in heavy industry—the shipyards and mines. By the Second World War things had changed again, with a great expansion of jobs in the car industry, electrical goods and light manufacturing. At each stage people looked at the changing lifestyles of those around them and concluded the militant working class of the past was gone. Around 1870 Thomas Cooper, a former activist in the Chartist movement 30 years earlier, surveyed the workers of the north of England and: Noticed with pain that their moral and intellectual conditions had deteriorated... In our old Chartist times, it is true, Lancashire working men were in rags by the thousands; and many of them lacked food. But their intelligence was demonstrated wherever you went. You would see them in groups discussing the great doctrines of social justice...they were in earnest dispute respecting the teachings of socialism. Now you will see no such groups in Lancashire. But you will hear well dressed working men talking of cooperative stores and their shares in them, or in building societies. And you will see others, like Why the Working Class? 13 idiots, leading small greyhound dogs, covered with cloth, on a string... Working men had ceased to think.1 Some 70 years later the idea that the old working class had disappeared became fashionable again. A broadsheet of the government’s Central Office of Information declared in 1962 that British society was characterised by a “swelling middle class”. There could be no return to the working class conditions of the 1930s because, “The average man...has made too great an investment in his own future as a middle class citizen and householder”.2 There was a serious academic discussion as to whether “affluent” car workers were “bourgeoisified”. Labour Party theorist Anthony Crosland wrote: One cannot imagine today a deliberate offensive alliance between government and the employers on the 1921 or 1925-6 model, with all the paraphernalia of wage cuts, national lockouts and anti-union legislation, or a serious attempt to enforce a coal policy, to which the miners bitterly objected.3 Yet a wave of workers’ struggles began in the late 1960s, culminating in confrontations that shook society as much as those of the 1920s, forcing a Tory government out of office in 1974. At the heart of the militancy were supposedly affluent workers in the car, mining and print industries. And the militancy was not finally destroyed until the defeat of the miners in a year-long strike in 1984-5 that involved the police occupation of mining areas. The restructuring of industry changes the working class and confuses observers, but it cannot do away with the central features of capitalism that lead to recurrent waves of class struggle. 1: Quoted in Max Beer, A History of British Socialism (1940). 2: Quoted in John Goldthorpe, David Lockwood and others, The Affluent Worker in the Class Structure (Cambridge, 1969). 3: Anthony Crosland, The Future of Socialism (London, 1956). 14 Education for Socialists The working class in the 21st century The restructuring of capitalism in the advanced countries is characterised by two trends: a growing proportion of the workforce is made up of white-collar workers, and service employment is growing more quickly than industrial employment. The trends should not be confused. Many service jobs are manual (bus drivers, dockers, refuse collectors) while a considerable proportion of manufacturing employees are white collar (progress chasers, design office staff). But the trends can give a misleading impression of what is happening to the class structure if you identify the working class solely with manual industrial workers. What has not changed, despite all the transformations in work brought about by restructuring, is the fact that the system is based on competition between rival firms. This leads companies to do their utmost to pump the maximum profit out of their workforce. As a section of workers grows in size, then the pressure on them to produce profits increases. When white-collar work was the prerogative of a relatively small number of male clerks in the 19th century, capitalism could afford to provide them with better salaries and conditions than the mass of manual workers. But 21st century capitalism depends on vast numbers of white-collar workers doing routine jobs. Many work for private firms in banks, insurance companies and advertising agencies. Others are employed by the state to carry out functions important to the system as a whole—training the next generation of workers, collecting taxes, protecting property, keeping people fit for work. These workers are exploited through the same methods as manual workers. Job evaluation methods pioneered in the textile mills, in steel plants and on car assembly lines are applied to civil servants, teachers and even university lecturers. One consequence of this change is that such groups now engage in characteristically working class forms of struggle. In Britain, strikes by teachers, civil servants, lecturers, journalists, nurses and white-collar workers in local government were virtually unknown until the late 1960s. They have become normal as strikes by old-style manual workers in the past 30 years. Why the Working Class? 15 Modern capitalist society is divided into two main groups as clearly as the 19th century society analysed by Marx or described in the novels of Charles Dickens. There is a small minority who have enough wealth to live a life of leisure if they wish, and there is a great mass of people who can only make a livelihood if they work for this minority. This division is more important than any other in society. It determines how much control you have over your life—whether you enjoy real choices or whether everything you do is subordinated to the need to work for others. It even determines how long you are likely to live, with the employing class in Britain today expecting to live, on average, more than ten years longer than the rest of us. It determines the quality of the clothes you wear, the car you drive, the food you eat and the goods you own. Analyse Britain according to this basic division and you find well over 75 percent of people are working class, in the sense of depending for their livelihood on selling their labour to the minority. Not all service employees or salaried staff are workers. In any class society there are gradations between the minority at the top and the mass of people at the bottom. In a slave society there are not just slave owners and slaves, but also a layer of slave drivers, who receive a small share of the wealth that comes from exploiting the slaves. In a capitalist society, there is a mass of small capitalists and self-employed business people as well as the major capitalists. There is also a layer of managers, top civil servants, police chiefs and so on who are paid much more than the value of any labour they perform in return for helping big capital exploit the mass of people. This layer is organised through bureaucratic hierarchies. Those at the top partake fully in the fruits of exploitation and have common interests with big capital. Those at the bottom get very little from exploitation and share many interests with the white-collar and manual workers below them. Low grade supervisors and line managers are paid a little more than those they order around, but rely on the same public services and can be hit just as hard by workplace closures and redundancies. The presence of this middle layer obscures the basic divide between the exploiting and exploited classes. But it does not do 16 Education for Socialists away with it anymore than the slope between a hill and a valley does away with the contrast between the two. Far from making up the majority of society, this middle class proper amounts at most to 15-20 percent of the population. Insecurity and struggle Another argument you hear about workers today is that globalisation has created such massive insecurity in employment that it is all but impossible to develop the strong workers’ organisations that existed in the past. Far from workers being able to challenge the state, they find themselves barely able to fight an individual employer. This argument suffers from two interrelated faults. First, workers have often succeeded in organising and fighting back against employers despite massive levels of job insecurity. Take the case of London’s dockers in 1889. This was a group with no security of employment. Gareth Stedman Jones’s book Outcast London quotes the findings of a parliamentary select committee on conditions on the docks in 1888: Bribery and favouritism were normal means of gaining employment in the docks. Treating the foreman to beer on the evening before was a frequent means of gaining employment in the docks the next day. Casuals in the docks applied daily for dock work at the gates where they were known by the foreman. This could not assure them a day’s work, since the foreman always employed a proportion of outsiders in order to increase the size of the casual pool. On the other hand, the foreman could punish long-term absence on the part of the casual workers by withdrawing his patronage. It was this precarious dependence of the casual on the foreman that maintained the casual fringe intact. Beatrice Webb, one of the founders of the reformist Fabian Society, described the position of dock labour in 1887 as “very hopeless”. “The employers were content and the men, although far from content, were entirely disorganised,” she wrote. Why the Working Class? 17 Conditions were not much more secure for metal and textile workers in the Russian capital, St Petersburg, at the end of 1904. According to the historian Gerald Surh: The turnover within the factory workforce in Petersburg seems to have been quite high... Unskilled and semiskilled workers were normally more volatile because they were more easily replaced... The lack of organisation and therefore protection at the workplace meant that the inevitable disputes between workers and foremen and managers were...frequently resolved...by resignation or dismissal.4 In both cases, mass strikes transformed the situation and encouraged hundreds of thousands of other workers to throw up new organisations of their own. When the London dockers struck in 1889, they shut down the city’s international trade for five weeks, won their economic demands and built a union of 25,000 members. Beatrice Webb highlighted the change: “What the men had achieved through organisation was not to be measured solely by advantage achieved in pay or the conditions of employment... We see the effect in the changed attitude of the employers as to casual employment.” In St Petersburg the transformation was even more dramatic. The unorganised workers of 1904 exploded into action after management victimised a wood worker in the Putilov plant. As Surh writes, “A mass meeting of 2 January [1905], attended by about 6,000 workers...enthusiastically voted for a strike at the Putilov plant... By Friday 7 January, 382 enterprises were on strike.” When the Tsar’s troops fired on a peaceful demonstration, the strike spread across the city and began a year of revolutionary upheaval that came close to overthrowing the regime. Such a sudden discovery of the power to fight back collectively can occur among the restructured working class of the 21st century. We have already had glimpses of it. In the forefront of the uprisings 4: Gerald Surh, 1905 in St Petersburg (Stanford, 1989). 18 Education for Socialists in Bolivia in 2003 and 2005 were workers from the mass of small workshops in the city of El Alto. The spring of 2006 brought sudden unexpected strikes and riots in the giant textile factories of Bangladesh, and January 2007 saw strikes and factory occupations by workers in Egypt. Capitalist restructuring can certainly decimate old, established sectors of industry and weaken the power of groups of workers that used to be among the best organised, as happened with the defeats of the miners and newspaper printers in Britain in the mid-1980s. But the same restructuring leads to a growth in the importance of new groups. Neither postal workers nor London tube workers were regarded as militant or powerful in Britain in the 1970s, but they have become so in recent years. We can expect other groups, at present largely unorganised—like those working in finance, call centres and supermarkets—to follow at some point. The very logic of capitalism creates discontent among those it exploits and oppresses, and at some point this bitterness will explode. The key question is not whether it will happen, but whether it will prove successful. The second major fault with the argument that precarious employment prevents workers from struggling is that, in most countries, it is a minority of workers who are in casual jobs. A study by the International Labour Organisation concludes: “While this type of employment increased substantially during the first half of the 1990s, the relative proportions of permanent and non-permanent jobs remained almost unchanged between 1995 and 2000: permanent (82 percent), non-permanent (18 percent).” The average conceals large divergences between countries, with a high point of 35 percent of workers in insecure employment in Spain. In Britain, according to the government statistical publication Social Trends, “As many as 92 percent of workers held permanent employment contracts in 2000 as compared with 88 percent who did eight years earlier.” Even in Third World countries such as India and Pakistan, where millions of workers move each year from the countryside to cities seeking work, there is relative security of employment for some sections. Employers like to have a stable element in their Why the Working Class? 19 labour force, to stop other employers poaching experienced workers when trade is booming and to encourage workers to identify with their particular firm in a way that discourages militancy. After all, it is a positive benefit to an employer if workers say, as a shop steward in a Leeds factory once told me, “This is the best firm in the country.” There has been an increase in casual employment in some countries in recent periods of capitalist crisis. But it is not an unstoppable trend in capitalism as a whole, and it certainly will not stop workers organising and rocking the system. Globalisation and workers It is often argued workers cannot fight back as they once did because globalisation of the world economy allows firms to shut down operations and reopen somewhere else. Globalisation certainly means finance houses and speculators can move massive amounts of money from one country to another at the click of a computer. There is also a trend for firms in one country to buy into those in other countries. But it is harder to move production from country to country than it is to move money. Productive capital is made up of factories and machinery, mines, docks and offices. These take years to build and cannot simply be carted away. Sometimes a firm can move machinery and equipment. But this is usually an arduous process and, before equipment can be operated elsewhere, the firm has to recruit and possibly train a sufficiently skilled workforce. In the interim, not only does investment in the old buildings have to be written off, there is no return on investment in the machinery. What is more, few productive processes are ever completely self‑contained. They depend on inputs from outside and links to distribution networks. So before a firm sets up a car plant it has to ensure there are supplies of quality steel available, secure sources of nuts and bolts, a labour force with the right level of training, reliable power and water supplies, a trustworthy financial system and a road and rail network capable of shifting finished products. It has to persuade other firms or governments to provide these things, and the process of assembling them can take months or years of bargaining. Multinational companies do not simply throw these assets away 20 Education for Socialists and hope to find them thousands of miles away because the labour is slightly cheaper or governments slightly more cooperative. The claim that firms find it easy to move production overseas is widespread in the US. But economist Tim Koechlin reports that less than 8 percent of US productive investment goes abroad. Job losses are mainly the result of firms cutting the number of workers they employ in existing plants, or closing some plants so as to concentrate production at those that remain. In Britain the pattern is much the same. The manufacturing workforce has been cut in half over the past 30 years, but total output has not fallen and each worker is producing twice as much as 30 years ago. In other words, each worker is more important to the system now than in the past. There are many important jobs that cannot be moved abroad—for example, in construction, newspaper printing, the docks, the civil service, post and telecommunications, local government, education, refuse disposal, food distribution and supermarkets. Even in the case of call centres, where some work has moved to India, employment in the sector in Britain continues to expand. Of course, firms do shift location and investments do not always occur in the same places. Restructuring often does involve moving production to a new area, and sometimes to another country, and this is likely to increase in the decades ahead. But such decisions incur costs and are never taken lightly. Firms that are restructuring usually prefer to act gradually, moving piecemeal from old plant to new, keeping supply and distribution networks intact and minimising dislocation. In the process, workers retain the power to stop production and to fight attempts to make them pay for restructuring. The most important effects of the movement of money from country to country are that it increases economic instability and makes people feel more insecure. Firms often play on this, threatening to move production abroad when they have little intention to do so, in the expectation that this will demoralise workers and persuade them to accept deteriorating conditions. In calling the bosses’ bluff, workers can begin to discover their capacity to fight for a world without insecurity. Why the Working Class? 21 The Shape of the Working Class Martin Smith Edited extracts from International Socialism 113 (2007) There was a time when one in four of the world’s big ships were built on the Clyde and more than 1 million of the UK’s workers were coal miners. Today the supermarket giant Tesco’s employs just over 250,000 workers—making it the biggest private sector employer.1 So began a report on BBC2’s Newsnight. The programme took for granted the “common sense” argument that the traditional working class in Britain is in terminal decline and is being replaced by a low paid, unorganised, part-time, casualised workforce based in the service sector. These conclusions are drawn from two main assumptions. The first is the decline in all major capitalist countries of manufacturing industries. The second argument is that the majority of people in Britain are now home-owning, white collar and middle class. Those who hold this view believe the country’s workforce looks something like an hourglass, with a large glass bowl at the top, containing around 70 percent of the population, which is doing very well or reasonably well. The bottom glass bowl contains the other 30 percent—the poor (unemployed, part-time workers) and low paid service sector workers. Arguments about the death of the working class are nothing new. Over the past 50 years they have regularly been resurrected. 1: Newsnight, 15 November 2005. 22 Education for Socialists French theorist André Gorz declared in an article written in early 1968 that “in the foreseeable future there will be no crisis of European capitalism so dramatic as to drive the mass of workers to revolutionary general strikes”, and the historian Eric Hobsbawm made a series of assertions that the working class was in terminal decline in the 1980s.2 Who is working class? Before we look at who makes up the working class in Britain today, it is important to define what makes someone working class. Marx argued that under capitalism there are those who own the means of production, the factories, offices, railways, etc—the ruling class; and the working class who sell their labour power in order to survive. In the Communist Manifesto he argued that the ruling class has developed “a class of labourers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market”. In other words, class is a social relationship. The Marxist historian G E M de Ste Croix put it the following way: Class (essentially a relationship) is the collective social expression of the fact of exploitation, the way in which exploitation is embodied in a social structure. By exploitation I mean the appropriation of part of the product of the labour of others: in a commodity-producing society this is what Marx called “surplus value”. A class (a particular class) is a group of persons in a community identified by their position in the whole system of social production, defined above all according to their relationship (primarily in terms of the degree of ownership or control) to the conditions of production (that is to say, the means and labour of production) and to other classes.3 2: A Gorz, “Reform or Revolution”, Socialist Register 1968. E Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes (London, 1994). 3: G E M de Ste Croix, The Class Struggle in the Ancient World (London, 1981). Why the Working Class? 23 However, today the structure of capitalist society is more complicated than simply being divided into two diametrically opposed classes—the ruling class and the working class. There is a substantial “middle class” in Britain. Sociologists claim it represents about 15 to 20 percent of the population—foremen, low grade managers, doctors, head teachers, etc. These people face contradictory pressures. On the one hand, their wealth and social position mean that they buy into the system; on the other hand, because they sell their labour power they too can find themselves in conflict with the system and look to a collective response. The class forces around them shape their reaction to events. It is interesting to note that a growing number of people describe themselves as “working class”. In 1994, 51 percent of those surveyed by Mori described themselves as working class; by 2002 it had risen to 68 percent. But Marxists reject the popular notion that what defines your class background has something to do with your lifestyle, income, accent or how you feel about your class position. In the early 1980s I worked as a civil servant in the London Passport Office. One member of staff used to come to work wearing a three piece suit, bowler hat, briefcase and a copy of the Financial Times under his arm. From his appearance you would have assumed that he was a top civil servant—he was in fact a filing clerk! Likewise the stereotypical view of an airport check-in worker is of a “corporatised glamorous woman”. Yet it was these women, in the summer of 2005, who brought British Airways to its knees when they organised an unofficial sit-in. When their working conditions were under attack they were forced to act collectively—in fact they went further than that: they adopted militant tactics associated with car workers in the 1930s or Glasgow shipyard workers in the 1970s. So it is important to understand that being working class is an objective relationship; the actual class position of individuals depends not on what they feel about which class they belong to, but whether they are forced to sell their labour power or not. Class position is not the same as class consciousness. Workers are still workers even if they vote Tory, own shares or buy their council houses. 24 Education for Socialists There are those who view the working class through the prism of what it looked like in the 1950s. They therefore conclude that because the number of miners in Britain in the 1950s was 600,000 and today it stands at less than 4,000 the working class is in decline. Capitalism is characterised by the constant revolutionising of the means of production. This means that from its earliest inception one of its key features has been restructuring: once-dynamic industries go into decline and new ones spring up. Alongside these grow newly developed towns and regions, and new working methods. Most importantly, this means that the working class is also constantly changing. This process of the constant revolutionising of the means of production was recorded by Marx. He wrote in the ­Communist Manifesto, “All old established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question.” This process is as old as capitalism itself. The basis of much of the Industrial Revolution was the textile industry. As the century wore on, coal and heavy industry became the backbone of British capitalism. These mainly male blue-collar workers are what shape many people’s vision of what a worker should look like. It is not true that these workers were automatically militant and pro-union. I once saw an exhibition at the now closed Labour History Museum in east London. It had a display of two photographs of a boilermaker in east London. In one photograph taken in 1886 he is standing there surrounded by apprentices, looking like a “middle class gentleman”. In the second, dated 1900, he is wearing a boiler suit with a union badge pinned on it, surrounded by a dozen men who look just like him. The transformation was down to two things, the deskilling of his job and the New Unionism strike wave that hit the country in 1889. Again in the 1930s Britain experienced the growth of new industries such as car manufacturing and light manufacturing goods. If you look at the car industry, much of it developed on new greenfield sites like Dagenham, Coventry and Oxford in the 1920s and 1930s. These factories were state of the art and hostile to trade unions. There were many at the time who said that it was impossible to organise in them because the workers had been bought off. Why the Working Class? 25 Similar things are said about bank workers, IT workers and media workers today. By the 1950s car workers were regarded as one of the best-organised and most militant sections of the working class. The experience of work and collective organisation and struggle brought about those changes. Socialists have to understand the conditions that create the working class as a “class in itself ”, and how that class can develop revolutionary ideas and become capable of making a revolution, become, as Marx put it, a “class for itself ”. Manufacturing The 2006 Social Trends survey notes: It is well known that the UK economy has experienced structural change since the end of the Second World War with a decline in the manufacturing sector and an increase in the service sector. Jobs in the service industries have increased by 45 percent, from 14.8 million in 1978 to 21.5 million in 2005, while those in manufacturing have fallen 54 percent from 6.9 million to 3.2 million over the same period. This decline in the numbers of workers involved in manufacturing was going on throughout the 20th century. At the same time we have seen a steady rise in the numbers of people working in the white-collar jobs and the service sector. Today white-collar and service sector workers are the majority. This trend also shows no signs of being reversed. However, manufacturing workers are still a large and powerful section of the working class. To put it into perspective, one out of seven of the British workforce is employed in the manufacturing sector. These workers often work in large and well-organised workplaces like engineering, car manufacturing and food production. Although their numbers have fallen, those workers who are still employed have become more and more productive and in some senses more powerful. Take, for instance, the UK car industry. Over the past 30 years there has been a huge fall in the numbers of workers employed 26 Education for Socialists in the industry. However, car production has barely fallen. At the height of UK car production in the 1970s Britain produced about 1.7 million cars a year. By 2005 it had only fallen to 1.6 million a year. New technology means that one car worker can produce eight times what their predecessors could 30 years before. Polycell, the wallpaper paste and DIY products manufacturer, has seen productivity rise by nearly 300 percent in the last 25 years. This is despite the fact that the workforce has halved over the same period. Each worker is more productive and consequently more powerful. White-collar workers When I started work as a civil servant at the London Passport Office 22 years ago I made the terrible mistake of believing I was going up in the world. I arrived at work wearing my best suit (in fact it was my only suit). I got the shock of my life: everyone else was wearing jeans. I ended up being assigned to a huge office, where half the people opened letters all day and the others stuffed envelopes. My job was to stamp the passports with a huge brass embossing machine all day long. I was part of a clerical production line. The nature of white-collar jobs has changed massively over the last 100 years. Clerical workers in the 19th century were regarded as middle class. Their pay, status and even dress made them more akin to managers. A clerical post was seen as a prized job and was usually a lifetime post. It was also a job that required a high level of skill. Very few clerical workers see themselves as that today. The growth of white-collar jobs throughout the past century has been accompanied by a huge growth in the number of women workers. Over the past 40 years office work has become increasingly deskilled and dependent on machinery. Work has become boring and repetitive. The introduction of costly technology (computers, faxes and photocopiers) has changed the pattern of work inside the office. A similar process has gone on in education, banking and local government. Investment in machines means that white-collar jobs are no longer nine to five. White-collar workers are expected to do shift work. Many offices are now open 24 hours a day. Certainly, in terms of pay, Why the Working Class? 27 a routine clerical worker is part of the working class. A low‑grade civil servant earns about £17,000 a year—no more than a manual car worker at Ford’s does. The growth of a large layer of middle management has accompanied this growth in white-collar jobs. Today the myth that white-collar workers are not part of the working class remains as strong as ever. Yet unionisation levels and strikes in this sector refute this myth. The drive to attack the working conditions, skills levels and pay of white collar workers over the last 30 to 40 years has been accompanied by a growth of trade unions in the public sector. Over the past 20 years Britain has witnessed a huge growth in call centres: there are approximately 850,000 workers currently employed in them. Some studies describe the workers in these centres as white-collar workers and others as part of the service economy. But they are also commonly described as the new coal miners of the 21st century. If you read most reports in the media, you would assume that these workers are completely atomised, have no power and face the constant fear of having their work outsourced to India or Romania. But again that is not a true picture. A series of recent studies shows that most of the companies which run these operations expect the number to keep on growing over the next few years, though not at quite the rate of a few years back. For every story about outsourcing to India, there is one about a new call centre being built in Britain, mostly ignored by the press. In fact a recent report in the Guardian notes that companies like Kwik-Fit Insurance and Powergen, who had outsourced their work to India, are now relocating back to the UK because they can’t find enough staff with the right level of technical skills and knowledge. Ironically, ICICI OneSource, a Mumbai-based outsourcing company, said it was building a new 1,000-person call centre in Belfast because of “its highly skilled workforce and relatively cheap property prices”. The service sector The increase in white-collar jobs has gone alongside the rise in service jobs. The image painted of the service sector is of low paid, 28 Education for Socialists part-time McDonald’s type jobs, but the reality is somewhat different. Many service workers are in what would be considered “old ­working class jobs”. Hospital ancillary workers, dockers, lorry drivers, bus and train drivers and postal workers all work in the service sector. These can hardly be described as “new” jobs: they have been an integral part of the UK workforce for a considerable length of time. And are their jobs much different from those in manufacturing? What’s the difference between someone who makes a clutch or mends or replaces a clutch? Likewise there is very little difference between a worker in a large fast food restaurant and a worker who works in a food processing plant. In fact the pressure on sectors of the service industry is to centralise and create powerful hubs. This leaves them open to worker pressure and organisation based on new groups of workers. Look at supermarket distribution. Tesco is now the biggest private sector employer in the UK. It has concentrated all its distribution of food and goods in half a dozen massive warehouses across the country. It also employs “just in time” methods of distribution. The warehouses are staffed by several hundred “pickers”—forklift truck drivers and support staff. If they withdraw their labour the whole system comes crashing down. This was demonstrated in the summer of 2005 when Asda distribution workers struck at a distribution centre in the north east. McDonald’s is one of the biggest corporations in the world. In what sense can those workers do any less useful or less real jobs than a worker making a tank or a Barbie doll? There are those who argue that the growth of the service sector has brought with it greater levels of job insecurity, and part-time and temporary working. It is of course true that neoliberalism has brought with it more flexible working but it has not brought about a radical overhaul of working life in Britain. According to Social Trends over a quarter of workers were working part-time in the spring of 2005; around four in five part-time workers were women. The levels of temporary work did increase during the mid-1990s, but have declined in recent years. In 1992, 6 percent of workers in the UK worked on a temporary basis and by 1997 it had peaked at 7.5 Why the Working Class? 29 ­ ercent; it has since fallen to 5.5 percent. The vast majority of workp ers have permanent jobs. In 1984, 82.8 percent of the ­workforce had a permanent job. By 1999 that had fallen by 1.1 percent to 81.7 percent. It is also worth noting that a further 3 million people had joined the workforce. Women workers More and more women are taking a central role inside the working class. Today 13 million women work, 49 percent of the total workforce. Women are now more likely to be union members than men. That is one of the findings of a report by the Department of Trade and Industry. The report, based on figures from the Labour Force Survey conducted in 2005, shows that for the second year running, the rate of female union membership has outpaced that for male employees. But women still earn less than their male counterparts. The most recent figures available show that average hourly earnings, excluding overtime, for full-time women workers are £10.56, compared to £12.88 for men. A government commission on women and work stated that the average pay gap between women and men was 17 percent in 2006. For average weekly earnings, the gap is wider—at 24.6 percent—partly because men are more likely to receive extra payments such as overtime, shift pay and bonus payments. The Equal Opportunities Commission estimates that, over a lifetime, women’s gross individual income is on average 51 percent less than men’s. Women make up the bulk of part-time workers—and the vast majority are mothers or wives (the proportion of women involved in part-time work is 44 percent compared to 8 percent of men). Their jobs fit around their family commitments and very often around the demands of childcare. Many part-time jobs are permanent and crucial to the economy. Today part-time working accounts for just over a quarter of all paid jobs. Migrant workers There are a large number of migrant workers who are forced to work illegally in Britain. For obvious reasons these people eke out a 30 Education for Socialists living and find themselves on the fringes of society. Estimates vary that there are between 500,000 and 2 million illegal workers in ­Britain. The government suggests that 13 percent of UK GDP can be accounted for by the so-called “black economy”. Many of these poor people find themselves working in terrible conditions without any protection and in fear of being deported. But migrants have been active in the labour movement since the beginning. Irish labour was a prominent feature of the Industrial Revolution and the trade union movement. Irish names can be found in the list of strikers in the Bryant and May match workers’ strike in 1888. Following the Second World War migrants from Italy and Eastern Europe joined those from the Commonwealth in plugging gaps in the labour force. The pattern of migration since the 1950s has produced a number of distinct ethnic minority populations in the UK. In 2001 the majority of the population in Britain were “White British” (88 percent). The remaining 6.7 million people (or 11.8 percent of the population) belonged to other ethnic groups. Of these smaller ethnic populations, “White Other” was the largest (2.5 percent—this is bigger now with the addition of at least 600,000 Eastern Europeans), followed by Indians (1.8 percent), Pakistanis (1.3 percent), those of mixed ethnic backgrounds (1.2 percent), Black Caribbeans (1 percent), Black Africans (0.8 percent), Bangladeshis (0.5 percent) and the remaining minority groups accounting for less than 0.5 percent of the population. People born outside the UK now make up more than 12 percent of the workforce. But even that doesn’t give the complete picture. The proportion of ethnic minorities and migrant workers in the workplace is even greater. There is an obvious reason for this. Most people uprooting and moving to another country tend to be young and certainly of working age (government statistics show that Black Caribbeans have the largest proportion of people aged 65 or over, reflecting their earlier migration to this country). The impact of migrant workers is much greater in some areas and some industries than others. A third of all the people living in London were born outside of Britain. The CWU post workers’ Why the Working Class? 31 union membership department claims that two major London ­sorting offices have workforces that are made up of 60 percent non UK born workers. A class in itself This article has demonstrated that the working class is going through a period of transformation. It is worth repeating that this is not a new phenomenon. I also believe that the working class in Britain has lost none of its essential characteristics—it is far from being the sort of flexible workforce predicted by many. The numbers who work in manufacturing industries may have shrunk, but those who remain still represent an important and powerful sector of the economy. Secondly, the working class has been supplemented by the massive expansion of the white-collar and service sectors. The people who work in these sectors are just as working class as any manual worker. They are forced to sell their labour, and suffer the hardships that manufacturing workers face. They have also created their own organisations to defend themselves—they have joined unions and taken strike action. Finally, the working class in Britain is being enriched with greater numbers of women workers, workers from ethnic minorities and a new wave of migrant workers who are also entering the workforce. Far from representing a threat to “traditional” working class organisation they are playing a more central role in trade union life. There are no objective reasons as to why the unions have to a greater or lesser extent failed to stop the neoliberal assault being pursued by the bosses and the government. The problems are subjective. Overcoming them is the key test for socialists and the trade union movement. 32 Education for Socialists Sample questions for discussion ›› How would you answer someone who claimed that class, in the Marxist sense, was no longer relevant? ›› How do the strands of anti-capitalism in the student movement in Britain in recent years fit with Hal Draper’s ­categories of “socialism-from-below” and “socialism‑from‑above”? ›› How does the Marxist concept of class help explain the revolutions in the Arab world in early 2011? What about the differences between Egypt and, say, Libya? ›› How might the changes to the working class in Britain affect the kind of bodies that would be created in a revolution here? Further reading A full version of Hal Draper’s The Two Souls of Socialism is available from the Marxist Internet Archive (www.marxists.org) along with the classic works by Marx and Engels dealing with this subject, such as the Communist Manifesto. Draper also wrote a volume entitled The Politics of Social Classes as part of his multi-volume work Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution (Monthly Review), which can sometimes be obtained second hand. A more recent work by August Nimtz, Marx and Engels: Their Contribution to the Democratic Breakthrough (State University of New York), deals well with the founders of Marxism and their relationship to class struggle. Chris Harman’s Revolution in the 21st Century is available from Bookmarks. He also wrote an article entitled “The Workers of the World” in International Socialism 96, which is available from http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj96/harman.htm The full version of Martin Smith’s article, which appeared in International Socialism 113, is available from www.isj.org.uk Also on the International Socialism website are two classic articles on class by Chris Harman and Alex Callinicos: www.isj.org.uk/ ?s=resources#classarticles