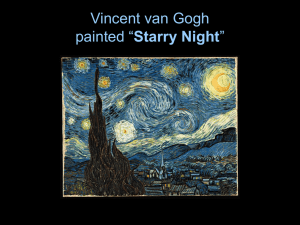

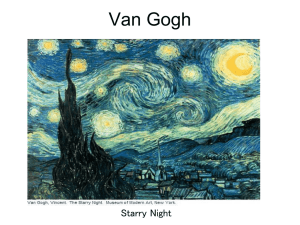

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995 - digitale bibliotheek voor de

advertisement