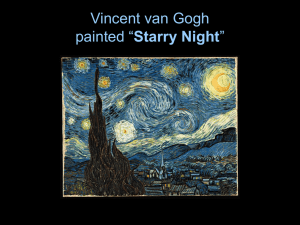

The Illness of Vincent van Gogh

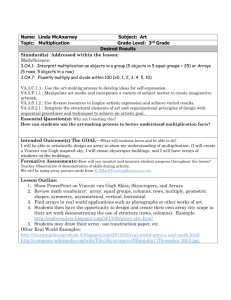

advertisement