Defendant-Appellee Brief

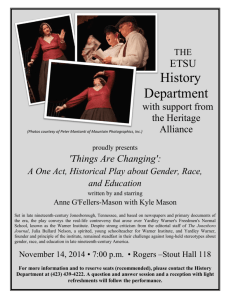

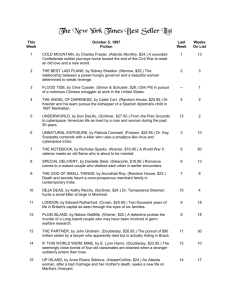

advertisement