notesontheprogram - New York Philharmonic

advertisement

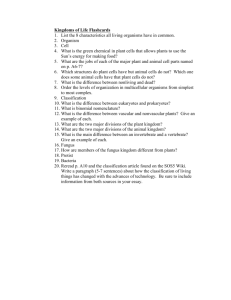

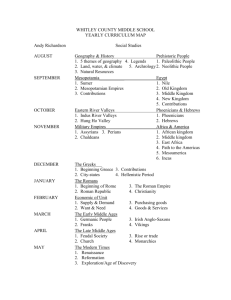

01-23 Capucon_Layout 1 1/14/14 3:43 PM Page 29 NOTESONTHEPROGRAM BY JAMES M. KELLER, PROGRAM ANNOTATOR The Leni and Peter May Chair The Enchanted Kingdom, Op. 39 Nicolai Tcherepnin N icolai Tcherepnin graduated from the University of Saint Petersburg and, in 1898, from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, where he was influenced by his composition professor, Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Following a few years of directing music at the Tsar’s Imperial Chapel, he joined the Conservatory’s faculty and became the first teacher of conducting in Russia. He himself was an important figure on the podium, overseeing the notable Russian Symphonic Concerts series and appearing often as guest conductor with the Russian Musical Society and the Moscow Philharmonic, as well as at the Mariinsky Theatre. This brought him into contact with the impresario Serge Diaghilev, who invited Tcherepnin to conduct the groundbreaking 1909 Saison Russe in Paris as well as many later appearances of his company, Les Ballets Russes. Two of Tcherepnin’s scores were presented as ballets by that troupe: Le Pavillon d’Armide (1907) and Narcisse et Echo (1911). When the trauma of the Russian Revolution broke out, Tcherepnin fled with his family to Tbilisi, Georgia, and then settled in the suburbs of Paris in 1921. There he became involved with the ballet troupe headed by Anna Pavlova; founded and directed the Russian Conservatory in Paris; and began disseminating the music of forward-thinking young composers through the publishing house founded some years earlier by Mitrofan Belaiev. Tcherepnin was a popular figure among musicians both in his native Russia and in Paris, which did not lack for expatriate Russians, and his social circle included such notables as Lyadov, Cui, Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky, and Prokofiev. His symphonic sketch The Enchanted Kingdom dates from 1909–10 and could be considered a proto-Firebird. Diaghilev eventually found his man for The Firebird in Stravinsky, but not before he had approached three (possibly four) other composers, of which Tcherepnin was the first. The Enchanted Kingdom, writes Richard Taruskin in his book Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, contains the music [Tcherepnin] had composed on commission for the first original ballet to be presented in Paris under the aegis IN SHORT Born: May 15, 1873, in Saint Petersburg, Russia Died: June 26, 1945, in Issy-les-Moulineaux, a suburb of Paris, France Work composed: 1909–10; published in 1912 under the French title Le Royaume enchant World premiere: March 13, 1910, at a concert of the Russian Symphonic Society sponsored by the publisher Mitrofan Belaiev in Saint Petersburg New York Philharmonic premiere: these performances Estimated duration: ca. 14 minutes JANUARY 2014 | 29 01-23 Capucon_Layout 1 1/14/14 3:43 PM Page 30 of the Diaghilev enterprise — none other, of course, than The Firebird. The enchanted kingdom of Tcherepnin’s title is that of the sorcerer Kashchei, whose evil spells Prince Ivan shatters with the help of the magical Firebird. With her song, the Firebird lulls Kashchei and his cohorts to sleep while she reveals the secret of his vulnerability to the young Prince. The score bears this epigraph (here presented in David Brown’s translation): A spellbound calm binds the kingdom of Kashchei — a calm veiled in gentle tinklings, in fresh dawn breezes. Neither the laments of enchanted strings nor magic riddles can break this slumber, this spell of sleep. Drowsy and sweet are the strains of the Firebird. Night descends. A black horseman enters the sleeping kingdom of Kashchei. Barely heard in the silent kingdom’s enchanted quiet are the tiny bells — the gentle breezes scarcely stir. The Enchanted Kingdom paints an evocative and magical landscape. Tcherepnin was fond of spotlighting individual instruments through momentary solos, always demonstrating an exquisite sense of orchestral balance. The work proceeds episodically; like many of his modernist contemporaries, Tcherepnin was more interested in the effect achieved by the gradual unrolling of material than in the tightly argued musical logic of classical tradition. The harmonic rhythm of The Enchanted Kingdom is often exceedingly slow, with bass notes sometimes being held unchanged through several pages of the score; the effect is curious and unsettling, a contra- A Composing Dynasty The name Tcherepnin has been threading through concert music for four generations. Nicolai Tcherepnin, the composer of The Enchanted Kingdom, stands at the head of this musical dynasty, but his son Alexander Nicolaievich Tcherepnin (1899–1977) was already a highly esteemed composer during his father’s lifetime; his path led from France, where his family had settled in 1921, to China and Japan, then back to Paris for the years of World War II, and finally to the United States, where he lived first in Chicago, then in New York. Alexander had two musical sons with his wife, the pianist Ming Tcherepnin. The elder, Serge (born in 1941), taught in the early 1970s at the California Institute of the Arts, invented an electronic synthesizer (called the Serge Modular), and continues to develop technologically advanced sound-generated equipment. The other son, Ivan (1943–98), taught at the San Francisco Conservatory, Stanford University, and eventually Harvard, where he directed that university’s electronic music studio. Ivan’s sons, Stefan and Sergei Tcherepnin, continue the family tradition. Both are active in the New York arts scene: Stefan as a composer and performer of acoustic and electronic music (often creating works that relate to specific visual or spatial artworks), and Sergei in exploThe dynasty continues: Sergei Tcherepnin creating a site-specific composition at the Portland Institute for rations of the intersection of sound with physical materials, as in sound-installation pieces. Contemporary Art, in 2013 30 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 01-23 Capucon_Layout 1 1/14/14 3:43 PM Page 31 dictory sensation of busy activity on the surface but profound stasis overall. The opening tempo of Moderato tranquillo, quasi andantino is maintained through more than half the piece, but after a pause the flavor changes to a still broader Sostenuto maestoso for a contrasting second section, almost pointillistic in the raindrop staccatos that range through the orchestra. This episode soon cedes to the return of a melody intoned earlier by various soloists. Themes from the beginning are recalled at the very end — murmuring violins, questioning melodic gestures — before the haunting vision of the enchanted kingdom fades away to the land of memory. Instrumentation: four flutes (one doubling piccolo), two oboes and English horn, three clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass drum, orchestra bells, xylophone, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Sources and Inspirations The Firebird, which figures prominently in Tcherepnin’sThe Enchanted Kingdom as well as in the eponymous Stravinsky ballet, is a common element in folk tales of many countries. In the Russian and Slavic versions that Tcherepnin would have known, the Firebird tends to be a magical bird that brings blessings, but may also act as a harbinger of doom. Its vibrant red, orange, and yellow plumage glows with a fiery intensity that does not diminish, even if plucked from the bird. Tales of the Firebird typically involve a hero who finds a lost tail feather, or hears the bird’s seductive song, a discovery that sets him off on a quest to find and capture the elusive, enchanting creature. Across folk tales from different countries, the quest is inevitably a difficult journey, with travels to faraway lands and encounters with magical helpers, in search of a great treasure that does not always result in the expected happiness. The Firebird, as illustrated by Ivan Bilibin for a Russian fairy — The Editors tale, in 1901 JANUARY 2014 | 31