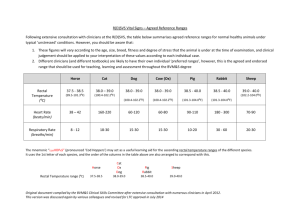

Quality Management and Quality Assurance in Long

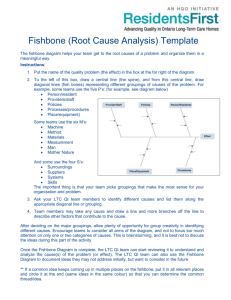

advertisement