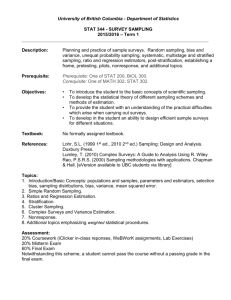

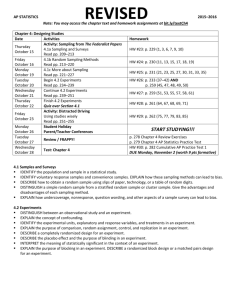

Sampling Methods for Web and E-mail Surveys

advertisement