life - 1 - Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts

advertisement

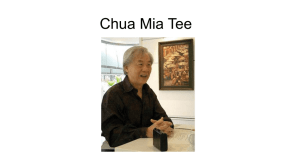

PART C The Temper Trap New song inspired by Hackney riots C3 Fashion parade Wilfred Lau speaks Stars shine at Melody Awards Joey Yung’s new beau goes on the record C10 C12 MONDAY, JUNE 25 2012 Painter Chua Mia Tee may not be a household name, but his work is everywhere, including on Singapore’s currency which carries his portrait of President Yusof Ishak. HUANG LIJIE talks to the artist known for his realist style. C6 DESIGN: LEE CHEE CHEW PHOTOS: KUA CHEE SIONG, UNIVERSAL MUSIC SINGAPORE, AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE, APPLE DAILY C6 LIFE! People MONDAY, JUNE 25, 2012 Painter of presidents and koi Although known for his portraits of prominent people, Chua Mia Tee is also inspired by nature P Huang Lijie ainter Chua Mia Tee may not be a household name but anyone who carries cash would be familiar with his work. His portrait of Singapore’s first president, Yusof Ishak, is used in the portrait series of currency notes here. You might have also come across his oil paintings of koi or Chinatown in offices and boardrooms. Or perhaps you were introduced to his iconic paintings depicting socially charged scenes such as National Language Class and Epic Poem Of Malaya through the critical writings and stage plays they inspired. His paintings have been picked by the National Heritage Board to be displayed for the world to see on the Google Art Project. For someone whose works have become ubiquitous icons of Singapore’s social, cultural and political history, Chua is refreshingly down-to-earth. The well-known portraitist, who has painted the movers and shakers of Singapore such as banker Wee Cho Yaw and five former presidents, was obliging when his portrait was photographed by Life!. The sprightly 81-year-old followed directions without questions and made no fuss about posing in the heat outdoors. He also calls the next day after the interview to apologise embarrassedly for not inviting this reporter to stay for dinner the night before. He had not expected the interview to end late and so had not instructed his domestic helper to prepare an extra portion. Chua lives in a semi-detached house off Dunearn Road with his wife, painter Lee Boon Ngan, 73. Their home is simply furnished except for the walls. Paintings fill the walls like tiles in a tightly wrought game of Tetris in the living room. Works (landscapes and portraits by him, vibrant paintings of flowers by her) either compete for the limited wall space or are stacked on easels in corners of the room. It feels like a homey art gallery and, occasionally, ends up being one too. When art collectors-turned-friends visit Chua at home, they sometimes cajole him to sell them the paintings off his walls. A large oil painting of a waterfall in China’s Jiuzhai Valley, painted by him in the 1990s, was sold recently to a long-time collector-friend. Chua says in Mandarin: “The collector wanted to buy the painting many years ago but I said no because I wanted it for myself. Recently, he asked to buy the painting again and I found it hard to reject him because of how long he has persevered.” He jokes that he also “could not resist the temptation” of the six-figure sum offered. His works typically sell for upwards of $40,000. My life so far “I am after realism in my paintings so it would be an insult to the people I paint if I gave them extenuated limbs and made them look like they are starving.” On his style of painting “At first, money didn’t matter to me. Later, I learnt the value of money. Now, I no longer need money. My pursuit in art is driven by happiness.” During his schooldays, Chua Mia Tee excelled in calligraphy and drawing and his father encouraged his interest in art. ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG He says: “My wife has been chiding common people and their struggle for me to stop selling paintings in my collec- independence. Theatre company spell#7 tion. She is worried that I will regret hav- staged a play based on National Language ing no more paintings of my own left for Class, and with the same title, in 2006 myself.” and 2008. It also produced a play inHeeding her advice, he has taken to spired by Epic Poem Of Malaya, also bearsquirrelling away works of sentimental ing the same name, in 2010. value to the second floor of his home. Chua’s more recent works may lack He is unabashed about his commercial the nationalistic fervour of his earlier success as a painter. He recounts with works, but he maintains that he has not quiet pride, for exlost his vision as ample, how his sean artist. THE LIFE! INTERVIEW WITH ries of koi fish He says matpaintings, which ter-of-factly: “I he began in the have always paintlate 1990s, were so ed what interests popular that other me.” artists began mimicking him. The Singapore River and Chinatown His art market appeal belies the signifi- figured frequently in his paintings from cance of his four-decade-long career as a the 1980s because the neighbourhoods Singaporean artist. that he grew up in were undergoing draMr Low Sze Wee, 42, director of the matic changes. And koi fish found their curatorial and collections division at the way onto his canvas in the 1990s because National Art Gallery, Singapore, says he was captivated by their beauty. Chua comes from the generation of SingaHe adds that he was not aware his pore artists who emerged during the social realist paintings have inspired 1950s and is widely recognised for his “ex- plays. cellent draughtsmanship and oil painting “How people choose to interpret my techniques”. paintings is entirely up to them,” he says. He adds that Chua is also often associThe guiding principle for his journey in ated with the development of social real- art has always been to follow his heart, a ist art in Singapore in the 1950s and belief instilled in him since he was young 1960s, when many of his works, includ- by his father, an art lover. ing National Language Class and Epic Chua was the second of two children Poem Of Malaya, vividly portrayed the and the only son born to a well-to-do social conditions and aspirations of the family in Shantou, China. His father was Chua Mia Tee Chua Mia Tee (left) around three years old with his father Chua Yam Nee (seated) and two of his father’s friends in China. He married Madam Lee Boon Ngan (right) in 1962. On putting his fine art career on hold in the early years to provide for his family “My children had an interest in art, but they chose to pursue careers in science because they felt they couldn’t rival me.” “I paint workers and labourers because I empathise with how difficult their lives are. I have felt the same struggles and the bittersweet things in life.” On his paintings of factory life “A good portrait reveals the subject’s personality, through elements such as facial expression and attire. It must also convey the subject’s standing in society.” On what he pays attention to when painting portraits On a recent family holiday in Shanghai, (from left) daughter Chua Yang, Chua, granddaughter Bernice Chua, wife Madam Lee, daughter-in-law Mrs Chua Hong, grandson Ignatius Chua and son Chua Hong. PHOTOS: COURTESY OF CHUA MIA TEE On why his son and daughter did not follow in his footsteps a businessman who owned a few iron manufacturing shops in Shantou and his mother was a dentist. At the age of six, he fled with his family to Singapore to escape the second Sino-Japanese War in China. The family settled in a shophouse in Boat Quay and Chua’s parents used their savings to start a provision shop in Havelock Road. Life then was difficult, but all he remembers was how much he enjoyed drawing as a pupil at the now-defunct Tuan Mong School in Tank Road and his father encouraging him to pursue his interest in art. He says: “My calligraphy and drawings were peerless and they were always put on display in school. In those days, few parents approved of their children showing an interest in art. It was considered a useless pursuit. But my father, who was an avid self-taught painter, believed in my talent.” The elder Chua was so supportive that, even during World War II, he would buy his son Chinese calligraphy ink. The family, which had escaped to a small Indonesian island, was able to make ends meet by farming. They returned to Singapore after the war and Chua finished primary school before attending Chung Cheng g High g School and then enrolling g at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (Nafa). Mr Chua Kah Pin, 78, a retired piano teacher and a friend of the artist since their schooldays at Nafa, says in Mandarin: “Mia Tee was not your usual bohemian-type artist. He was very disciplined and he would practise painting on his own for hours after class.” Chua also devoured art catalogues and writings on art history in the Nafa library. The books opened the doors to realist art and introduced him to famous European old masters of the style including Rembrandt and Francisco Goya. He says: “I was impressed by their skill and ability to render things in real life in such a moving way.” His zeal for art and his well-honed drawing technique made him stand out among his peers at Nafa, though not always in a good way. Chua’s friend Kah Pin says: “When it came to drawing from life, Mia Tee was especially fast and skilful, so it’s no surprise that some students were annoyed with him. “Mia Tee was never boastful but his comments were sometimes misunderstood by others. For example, if someone asked him why he drew so fast in class and his matter-of-fact reply was ‘It is not that difficult’, they would be offended.” Some of the students took out their resentment on Chua by playing pranks on him. They scared him in school one night by pretending to be ghosts. Recalling the incident, which left him green in the face, Chua says: “They could have been jealous and they probably also thought I was arrogant because I did not hang out with them. But I have no ill feelings towards them.” He is candid about how, when he was younger, he did not hold some of his art teachers in high regard. “When it came to drawing from nature and life, I was better and faster,” he says. “But I have since grown to recognise our differences in style and perspective, and I respect them for their point of view as artists.” Despite his single-mindedness about painting, he did not launch his career as an artist until 1974. After graduating from Nafa in i 1952, Chua was an art teacher at the academy before he joined an international advertising company as a designer. The art director of the ad agency offered him a deal he could not refuse. He says: “They were offering me a monthly salary of $400, more than twice my pay as an art teacher. It happened that I also needed more money then because I was about to get married and start a family.” He has two children, both in their 40s, as well as two teenage grandchildren. His older son, Chua Hong, is the science and technology faculty dean at the Technological and Higher Education Institute of Hong Kong. His daughter, Chua Yang, is an obstetrician and gynaecologist in private practice here. After five years at the ad agency, Chua became a freelance illustrator, taking on projects such as textbook illustrations because he could earn between $2,000 and $3,000 every month. He continued to paint whenever he found time. He says: “I still wanted to be a painter and I knew that my job as a commercial artist was temporary.” In 1974, he was invited by a nowdefunct art gallery in Telok Ayer to stage his first solo art show. He exhibited more than 20 paintings and sold most of them. The exhibition marked the turning point. He became a full-time artist. Chua acknowledges that there have been criticisms in the art circle about his work lacking originality and looking too much like photographs. He says: “When I was younger, I used to be angry at such attacks on my work. But now, I know that as long as I paint well, it doesn’t matter what people say.” He is similarly nonchalant when asked about how he has yet to be named a Cultural Medallion recipient. “I am not interested in such awards. It doesn’t mean that if you don’t have an award, you are no good,” he says. “If someone wins the award, he could perhaps use it for publicity, but it doesn’t raise the quality of his art.” He also stresses that although he is a realist painter who seeks to convey real life in his pictures, he does not merely record what the eye sees. He says: “My paintings are based on real life but there is also creativity involved in what I choose to paint and how I compose the painting.” Forty years on, the octogenarian has not slowed down. He still takes about the same time to complete a work: between two and four weeks on average, depending on the size of the painting. But the frequency at which he churns out works has relaxed. These days, he paints when he feels the urge. Since the start of the year, he has completed two large-scale koi paintings measuring 2m by 1.5m, both of which have been bought by collectors. Mostly, he passes his time leisurely, with activities such as daily brisk walks at the Botanic Gardens and going on holidays with his family at least once a year. For an artist who has done it all, he still has one wish. “I would like to go to Mongolia to see wild horses galloping across the plains. I want to paint that majestic sight.” lijie@sph.com.sg