Conditions under Which Women Behave Less/More Pro

advertisement

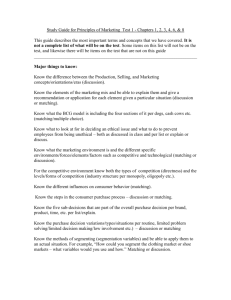

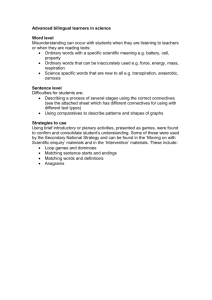

Conditions under Which Women Behave Less/More Pro-Socially than Men Evidence from Two Field Experiments Stephan Meier* Harvard University June, 2005 Abstract: The behavior of others and the price of giving are two important determinants of contributions to public goods. This paper tests in two field experiments, whether men and women differ in their reaction to either a change in the behavior of the average group behavior or the price of giving, i.e. a matching mechanism. The results of the field experiment show that men and women do not differ in their reaction to a matching mechanism. However, substantial gender differences can be detected with respect to social comparison. Men behave stronger in line with average group behavior, whereas women seem to be insensitive to information about the group behavior. Keywords: Field Experiment, Gender, Charitable Giving, Matching Mechanism, Social Comparison JEL classification: C93, H41, J16 * WAPPP, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 79 JFK Street, Cambridge MA 022138; Phone: +1(617)496-4786; e-mail: smeier@iew.unizh.ch. I am grateful for helpful comments from Iris Bohnet, Hannah Riley Bowles, Christian Vossler and seminar participants at Harvard University and Georgia State University. I thank the administration of the University of Zurich, especially Thomas Tschümperlin, for their support of the project. I also thank the Swiss National Science Foundation for their financial support. I wrote this paper while I was a visitor at the Women and Public Policy Program at Harvard University, and would like to acknowledge their generous hospitality. 1 Do men and women differ in their pro-social preferences and therefore in their propensity to behave pro-socially and to contribute to public goods? The empirical results on the question whether there are gender differences in pro-sociality are rather unclear and go in all possible directions (for an excellent survey, see Croson and Gneezy, 2005). Women are, for example, found to be less corrupt than men (Swamy et al., 2001). But men are more generous in tipping (Conlin et al., 2003) and are found to be more helpful in general (Eagly and Crowley, 1986). These field studies often have the problem of either not fully being able to control for income and wealth differences between men and women or they look at very particular ‘generous activities’ (such as helping a stranger changing a wheel). Both limitation of field studies make it difficult to isolate gender differences in pro-social preferences. Therefore many studies look at gender differences in laboratory experiments. These experiments, e.g. prisoner’s dilemma or dictator games, allow controlling for a lot of potentially confounding factors. But the experimental evidence is as mixed as the field studies.1 Whereas in some studies women contribute less to a public good than men (e.g. Brown-Kruse and Hummels, 1993), in other studies women are more generous in dictator games (e.g. Eckel and Grossman, 1997). These results are based on very different experimental designs which make it on the one hand difficult to compare the studies but on the other hand allow to isolate conditions under which men are more generous and vice versa. To isolate such conditions allows explaining the seemingly contradictory empirical evidence on men and women’s pro-social preferences. This paper investigates two very important determinants for contributions to public goods and whether men and women react differently to these determinants in two field experiments. It analyzes a unique naturally occurring decision setting. At the University of Zurich every student has to decide each semester whether he or she wants to donate money to two social funds managed by the University. In the first field experiment the effect of the price of giving is investigated. Standard economic theory would predict that people undertake an activity more if it becomes cheaper. To test whether men and women differ in their price sensitivity, a matching donations mechanism was implemented which increased the donations of randomly selected students either 25 or 50 percent, respectively. Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001) show in a series of experimental studies that the sensitivity to the price of altruism differs between men and women. As a result, men are more generous, when it is relatively cheap, whereas women behave more pro-socially when the price increases. However, the results of the 1 For a survey on the experimental literature, see Eckel and Grossman (2001). 2 field experiments do not support this result. Men and women do not differ in their reaction to a matching mechanism. The second field experiment analyses another important determinant of peoples’ behavior: social comparison. With respect to contributions to public goods, the behavior of others serves as the descriptive norm about the appropriate behavior (e.g. Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). In the field experiment, subjects were provided with either the information that many other students contribute to the two funds or that only few other students do so. As the variation of students contributing result from different time periods (the last semester vs. a ten year time period) no deception was used. The main contribution of this paper is to show that men and women react differently to social comparison. In the field experiment men react strongly to the behavior of others while women seem to be less sensitive to group behavior. The result from the field experiment is in line with research in social psychology on gender differences in interdependent preferences. Men are oriented more towards the group behavior while women are more sensitive to the behavior of close friends (Baumeister and Sommer, 1997; Gabriel and Gardner, 1999; for a countervailing perspective, see Cross and Madson, 1997). The results of this paper add a potentially important factor to the discussion in economics about gender differences in pro-sociality, namely social comparison. Men and women seem to differ in their reaction to the behavior of others, which could explain some of the seemingly contradictory results about when men are more pro-socially than women and vice versa. The paper proceeds as following: Section II reviews the differences between the context of previous studies. Special attention will be given to gender differences in social comparison. Section III presents the data set and the experimental intervention. Section IV presents the empirical result. A discussion of the results and conclusions are given in Section VI. II. Previous studies and its different conditions The empirical results on gender differences in cooperative behavior are inconsistent. While some studies show that women behave more pro-socially, the results of other studies seem to support the opposite. However, the various studies differ in the structure and the context of the decision situation. On the one hand, this makes a comparison difficult, but on the other hand, allows hypothesizing about critical factors which might explain the seemingly inconsistent results about men and women’s prosociality. So far, two major factors have been isolated in the economics literature which influence men’ and women’s pro-social behavior differently: (1) risk, and (2) price of giving. I will add a third factor 3 which has the potential explaining gender differences in pro-sociality: (3) aspects of social comparison in a decision setting. (1) Gender and Risk The level of risk involved in a decision situation might explain gender differences.2 Eckel and Grossman (2001) observe that in situations where risks are involved, there is no differences between men and women in their cooperative behavior. However, for decisions with no risk, women would be expected to be more generous. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that men and women do not differ in their proposal in the risky first stage of an ultimatum game (e.g. Solnick, 2001) or in the offer made on the risky first stage of a trust game (e.g. Croson and Buchan, 1999; Ashraf et al., 2004). Based on a large number of subjects Buchan et al. (2003) found that in the first stage of a trust game men are found to be more trusting. But women seem to be more generous and socially oriented in not risky dictator games (Eckel and Grossman, 1997; Bohnet and Frey, 1999) and the risk free second stage of trust games (Buchan, Croson and Solnick, 2003). According to these results, one would expect that women are more generous in the risk-free decision to contribute to two social funds. But contradictory evidence show that even in situation without any risk involved, either no gender difference can be detected (Bolton and Katok, 1995) or men are more generous than women (Conlin, Lynn and O'Donoghue, 2003 for evidence on restaurant tipping). This seemingly contradictory evidence even in situations in which no risk is involved, lead to the hypothesis that men and women differ in their pro-sociality depending on the price of giving. (2) Gender and the Price of Giving The relative price matters for altruistic activities as it does for other goods and activities. The cheaper it is to donate money or help others, the more people undertake this activity. This fact is especially well established concerning the possibility to deduct donations from the tax bill (see, e.g. Auten et al., 2002). Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001) show that men and women react differently to a change in the price of giving. While women are less price sensitive, men react strongly to the price of giving (see also the evidence in Ashraf, Bohnet and Piankov, 2004; Cox and Deck, 2002; Andreoni et al., 2003). As the demand curve for generous behavior of men and women cross, it is possible to explain why men are 2 Differences in risk attitudes for men and women seem to depend on the context as well. While in abstract decision settings women show higher risk aversion, in a concrete decision situation, no gender differences could be detected (Schubert et al., 1999). 4 more generous when the price of giving is low, whereas women become more generous the more expensive it is to be nice towards others. According to these results, one would expect that men react stronger to the matching mechanism, which increases the effectiveness of a donation. However, the different price sensitivities may also depend on the framing of the price and on the particular cooperative activity in question. For example, an equivalent change in relative prices framed either as a matching or as a rebate mechanism might have very different effects (Eckel and Grossman, 2003) – for men and women. In a situation where the price is varied not in a simple dictator game but in a punishment game, Eckel and Grossman (1996) conclude that “men’s behavior appears to be unaffected by its relative price, (…)”. More evidence is therefore needed to get a clearer picture on how the price of giving influences the gender differences. (3) Gender and Social Comparison The literature on cooperation in social dilemmas has isolated social comparison as a crucial factor explaining cooperative behavior (in economics, see e.g. Fischbacher et al., 2001; Keser and van Winden, 2000; Frey and Meier, 2004b; Andreoni and Scholz, 1998). People’s willingness to contribute to a public good increases with the proportion of others who do so. Nobody wants to be the ‘sucker’ who single-handedly provides the public good while all the others free-ride. The behavior of others serves as a descriptive norm about the appropriate behavior in a given situation (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). In the case of contributing to a public good or donating to a charity, the behavior of others might also serve as a signal for the quality of the public good or the charity (Potters et al., 2004; Vesterlund, 2003). In either case, the effect of the information about others people’s behavior depends on whether those other people constitute your reference group or not. If people receive the information about their reference group’s behavior, the social interaction effects are stronger than when people get information on behavior not of their reference group. Supportive of this conjecture is evidence found by Shang and Croson (2005b; 2005a). They find that donations in a National Public Radio campaign are higher, if potential donors were informed that a donor just gave x$ than when informed that a donor just gave y$<x$, which supports the general effect of social influence on contributions to public goods. However, they also varied the gender match (if a woman (men) called they told that he (she) just gave x$). If there was a match, the correlation between own behavior and behavior or the other person was stronger. With respect to the question whether men and women react differently to social comparison, it is crucial to think about potential gender differences not only with respect to differences in general 5 interdependence but with respect to whom men and women compare to. Probably men are not more independent and women not more interdependent, as proposed by Cross and Madson (1997). If it would, we would expect that women react stronger to social comparison than men. The related literature on conformity is consequentially not as conclusive. Some studies find that women conform more than men (e.g. Eagly, 1978), later studies this varies extremely with the situation (Eagly and Carli, 1981; Eagly and Chrvala, 1986). Rather, men and women differ in the type of interdependence. Men compare more with the broader group whereas women care more about close relationship (Baumeister and Sommer, 1997). Gabriel and Gardner (1999) show in their studies that men are more concerned with their group whereas women are more concerned about their close friends. This difference might explain why men are more likely to help a stranger while women are more likely to help friends and close individuals (Eagly and Crowley, 1986). According to this research in social psychology, we would expect that men and women differ in whether they got informed about what either the group average is doing or what their close friends are doing. Decision situations very much differ not only in the extent of allowing social comparison but also on the salience of either the relational or collective interdependence. The different reaction of men and women towards different kinds of social comparison might be a key in understanding seemingly contradictory gender behavior in different situations. In the following the effect of conditions on men and women are tested in two field experiments. III. Data Set and Field Experiments Data Set Each semester, all the students at the University of Zurich have to decide whether or not they want to contribute to two official social funds – in addition to the compulsory tuition fee. On the official letter for renewing their registration, the students are asked whether they want to voluntarily give a specific amount of money (CHF 7.-, about US$ 4.20) to a fund which offers cheap loans to students in financial difficulties and/or a specific amount of money (CHF 5.-, about US$ 3) to a second fund supporting foreigners who study at the University of Zurich. Without their explicit consent (by marking a box), students do not contribute to any fund at all. The panel data is composed of the decisions of all students for the twelve semesters since the winter semester 1998/99.3 3 For details on contribution to the two funds and an analysis of behavior over time, see Frey and Meier (2004a). 6 The two field experiments were undertaken in the winter semester 2002/2003. With the official letter for renewing the registration and the decision about contributing to the two funds, the administration supplied the students selected (1) with information about the matching donations mechanism (Field Experiment ‘Matching Donations’), and (2) with information about the behavior of other students (Field Experiment ‘Social Comparison’).4 (1) Field Experiment ‘Matching Donations’: Varying the Price of Giving In the first field experiment, 600 individuals of the student population were randomly selected and provided with the information about the matching mechanism. With the official letter for deciding on the contributions to the two social funds the selected students received a sheet of paper containing the following information: “If you contribute to both Social Funds, an anonymous donor matches your contribution with CHF 3” (treatment ‘Matching 25%’); or “CHF 6” (treatment ‘Matching 50%’). These matches result in a 25% and 50%, respectively, increase in the amount donated. The sheet of paper that the two treatment groups received differed only with respect to the amount matched. The subjects were informed that the matched money is split equally between the two funds. We therefore paid 822 CHF to both of the funds after the experiment. Due to the ‘institutional difference’ that freshmen have to pick up the registration form at the counter of the administration office, only students who decided at least once in the past are in the treatment groups. As some of the students decided not to renew their registration, we could observe the decisions of 532 subjects in the two ‘matching donations’ treatment groups. 5 Students decide anonymously at home about the contribution to the two social funds. (2) Field Experiment ‘Social Comparison’: Varying the Behavior of Others In the second field experiment, 2000 students of the student population were selected at random and provided with information about the behavior of other students. We provided 1000 students with the information that a relatively high percentage of the student population (64%) contributed to the two funds in the past, and another 1000 students with the information that a relatively low percentage (46%) contributed to the two Social Funds. The information is based on real contribution rates, but refers to different time periods. The higher contribution rate applies to the winter term 01/02. The lower contribution rate indicates the average over the last ten years. The sheet of paper that the two treatment groups received differed only with respect to the exact information given and a plural s for semester(s) 4 5 For other field experiments on charitable giving, see List and Lucking-Reiley (2002), Carpenter (2004), and Falk (2004). For details on the experiment and the overall effects, see Meier (2005a). 7 indicating the longer or the shorter time period. Due to the ‘institutional difference’ that freshmen have to pick up the registration form at the counter of the administration office, only students who decided at least once in the past are included in the treatment groups. Due to the fact that some students did not renew their registration at the University, we could observe the decisions of 1754 subjects in the field experiment on ‘social comparison’.6 Table 1 presents summary statistics of the data set used and of the treatment groups for the period in which the field experiment was undertaken. Two differences between men and women are most obvious: First, women are less likely to undertake a Ph.D. at the University of Zurich. For the control group around 20 percent of men are currently in the Ph.D. level while only 15 percent of women are so. Second, women are less likely to study economics. While about 15 percent of male students study economics, only about 6 percent of female students choose economics as their major subjects. As both differences might affect pro-social behavior, we will control for these factors (beside other influences) in the result part of the paper. Table 1 also computes the average past donation to the two social funds. Looking at the control group, we can see a slight gender difference in contributions to the two funds: men contributed more to the two funds in the past than women did. In the next section, this gender difference in pro-social behavior will be further analyzed. [Table 1 about here.] IV. Analysis and Results The potential gender differences in pro-social behavior will be analyzed in three steps: first, we look at the gender differences without any experimental intervention. Second, we report the results of the field experiment ‘Matching Donations’ and ask whether in the natural occurring situation men and women react differently to the price of giving. Third, we investigate the field experiment ‘Social Comparison’ and analyze whether men and women react differently to social interaction effects. Gender differences in pro-sociality The raw data of contributions to the two Social Funds at the University of Zurich shows that there is a gender difference in pro-sociality. Table 2 presents the share of persons who contribute to none of the two funds, to only one of the funds or to both funds. In the table the observations are pooled for all students in all available semesters. Students who were selected to be part of the field experiment are 6 For a detailed paper on the overall effect of the field experiment, see Frey and Meier (2004b). Meier (2005b) analyzes whether framing the information influences people’s behavior. 8 excluded in table 2.7 The descriptive statistics shows that women are less likely to contribute to the two funds than men. While 66.2 percent of men contribute to both funds, only 64.6 percent of women do so (t-test of differences: t = 5.174; p<0.001). Men are also less likely not to give at all compared to women. However, this difference is not statistically significant (p<0.61). Women are consequently more likely to give to only one of the two funds but not to both. As a result, women donate less on average than men do: men give on average CHF 8.29 while women donate CHF 8.18. The difference is statistical significant at the 99 percent level (t=3.117). [Table 2 about here] Female students differ in observable characteristics (i.e. being in the Ph.D. level or being an economist) as seen in the summary statistics, it is therefore important to control for variables which might influence the propensity to give and are correlated with the gender component. Panel I in table 3 presents a probit model, where the dependent variable takes the value 1 when the student decides to contribute to at least one fund, a 0 otherwise. The coefficients in a probit model are difficult to interpret. Therefore, marginal effects are computed which indicate how the probability of contributing changes compared to the reference group for dummy variables and how it changes if the independent variables change one unit for all continuous variables. The variable for gender is 1 for women and 0 for men. The regression analysis confirms the result from the descriptive statistics: women are less likely to contribute to at least one fund even after controlling for various observable differences between men an women. The probability that female students contribute to at least one of the two funds is, ceteris paribus, 2 percentage points lower than for men. This difference is statistical significant at the 99 percent level. The control variable show that the probability to contribute decreases with the number of semesters (equivalent to the number of decisions), being a foreigner, being a freshmen, being a Ph.D. student, and studying economics8. On the other hand, the probability of contributing increases with age, being married, and being in the main stage of the University curriculum. Panel II of table 3 presents an OLS-regression where the dependent variable is the donation in Swiss Francs. The result of the descriptive analysis is confirmed: women contribute, ceteris paribus, 0.33 CHF less to the two social funds (p<0.01). In sum, a small gender differences could be detected in the naturally occurring decision situation to contribute to two social funds at the University of Zurich. The 7 The results do not change if the differences are computed only for one particular semester. Frey and Meier (2003) show that the difference between economists and non-economists is due to a selection process and cannot be explained by the training in economic theory. For differences between male and female economists, see Seguino et al. (1996). 8 9 results are more in line with those previous results showing that women behave less pro-socially than men. [Table 3 about here] Field experiment 1: Gender and Matching Donations The first field experiment investigates how men and women react to a change in the price of giving. The matching mechanism which is offered randomly to some subjects makes a donation more effective and can therefore be seen as equivalent to a reduction of the price of giving.9 According to the results by Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001), men should react more to a change in prices. Figure 1 shows the proportion of students contributing to both of the two funds (as the matching was conditional on giving to both funds). The pattern in figure 1 shows that women seem to react slightly more than men to the matching mechanism. While in the control group, women are less likely to contribute to both funds, if offered a high or a low matching women become more likely to contribute to both funds than men. However, the difference is not statistically significant. Table 4 therefore provides a logit model with individual fixed-effects where the dependent variable takes the value 1 when the subjects decides to contribute to both funds, and 0 otherwise. Panel I in table 4 shows that in particular the high matching increases the probability of people contributing to the two funds. But panel II of table 4 shows that the differences between men and women are not statistically significant at a conventional level. The results of the field experiment can therefore not confirm the results from the laboratory study by Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001). If the price of giving is changed with a matching mechanism in the field experiment, men and women seem to have very similar price elasticities. [Figure 1 and table 4 about here] Field experiment 2: Gender and Social Comparison In the second field experiment, we were interested whether men and women differ in their reaction to social comparison. A gender difference in the field experiment would explain that men and women behave differently depending on the social comparison aspect of the decision situation. First of all, men and women do not differ in their expectations about the behavior of others. We asked 500 other students about their expectations of the proportion of students contributing to the two funds. 9 For a discussion of the differences between rebate and matching, see the lab and field experiments by Eckel and Grossman (2003; Eckel and Grossman, 2005). 10 There were no statistical significant differences in expectations between male and female. Men (N=120) expected on average around 58 percent of the students to contribute while women (N=130) expected on average about 55 percent to contribute. The differences is not statistical significant (p<0.28). Figure 2 shows the proportion of (male and female) students contributing to at least one of the two social funds. The proportion is computed either for subjects who were informed that 46 percent of the others contribute to the funds (treatment ‘Low’) or for subjects who were informed that 64 percent of the other students contribute to the funds (treatment ‘High’). The control group constitutes of students who did not received any information about the behavior of others. As could be seen from figure 2, the behavioral reaction of men is stronger than for women. More precisely, women do not react to the information about the behavior of others, while men substantially increase their pro-social behavior when faced with many others who contributed. No gender differences can be detected when confronted with only few people who contribute. [Figure 2 about here] Table 5 presents a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value 1 when the subjects decides to contribute to at least one fund, and 0 otherwise. Individual fixed-effects and time dummies are incorporated. Table 5 confirms that the different reaction between men and women to treatment ‘High’ is statistically significant at the 95 percent level controlling for individual time-invariant heterogeneity. Meier (2005b) reports gender differences with respect to focusing subjects not on the number of contributors but on the number of non-contributors. In the negative framing, no gender differences could be detected. It is, however, still unclear how the framing changes the perception of the descriptive norm. The gender differences in the field experiment ‘Social Comparison’ shows that, in the positive framing, men and women differ in their reaction to social comparison. [Table 5 about here] V. Conclusion The evidence on gender differences in pro-social behavior is mixed. Men and women differ in their pro-sociality depending on the conditions. This would explain the seemingly contradictory evidence based on cooperative behavior in different contexts and environments. This paper presents field evidence on pro-social behavior at a decision setting at the University of Zurich. All students are asked every semester to contribute to two social funds. The conditions under which students make their 11 decisions to behave pro-socially are manipulated in two large-scale field experiments. The paper therefore analyzes not only the level of contribution to the social funds, but investigates how pro-social behavior changes with the experimentally manipulated price of giving, and the experimentally induced beliefs about the behavior of others. The results from the field study show, firstly, that men are slightly more likely to contribute in this riskfree charitable giving context. Second, no gender differences could be detected with respect to the introduction of a matching mechanism. If the price of giving is changed with a matching mechanism, both sexes seem to be similarly price sensitive. Third, men and women differ in their reaction to social comparison. While the information that many others contribute to the two social funds does not change the pro-social behavior of women, it increases the contribution of men dramatically. The results of the field experiment on social comparison therefore add a so far neglected environmental factor to the discussion on explaining gender differences in pro-sociality. According to the results, one would expect men to behave more pro-socially when social comparison is most obvious. One potential explanation would say that men are more concerned with the group behavior than women as their interdependence is more collectively defined. This finding is not only important to explain seemingly contradictory results on gender differences, but also points out that in thinking about the effect of information on the social norm it is crucial to think about what constitutes one’s reference groups. As women are less oriented towards the group behavior, they seem to be less sensitive to the behavior of the group average. One easy further step to consolidate the finding of this study is to look for gender effects in the various (previous) studies on social comparison. 12 References Andreoni, James; Brown, Eleanor and Rischall, Isaac (2003). "Charitable Giving by Married Couples: Who Decides and Why Does It Matter?" Journal of Human Resources 38(1), pp. 11133. Andreoni, James and Scholz, John Karl (1998). "An Econometric Analysis of Charitable Giving with Interdependent Preferences." Economic Inquiry 36(3), pp. 410-28. Andreoni, James and Vesterlund, Lise (2001). "Which Is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in Altruism." Quarterly Journal of Economics 116, pp. 293-312. Ashraf, Nava; Bohnet, Iris and Piankov, Nikita (2004). "Decomposing Trust and Trustworthiness," Mimeo. Cambridge, MA: Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Auten, Gerald; Sieg, Holger and Clotfelter, Charles T. (2002). "Charitable Giving, Income and Taxes: An Analysis of Panel Data." American Economic Review 92, pp. 371-82. Baumeister, Roy F. and Sommer, Kristin L. (1997). "What Do Men Want? Gender Differences and Two Spheres of Belongingness: Comment on Cross and Madson (1997)." Psychological Bulletin 122(1), pp. 38-44. Bohnet, Iris and Frey, Bruno S. (1999). "The Sound of Silence in Prisoner's Dilemma and Dictator Games." Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 38(1), pp. 43-57. Bolton, Gary and Katok, Elena (1995). "An Experimental Test for Gender Differences in Beneficent Behavior." Economics Letters 48(3), pp. 287-92. Brown-Kruse, Jamie and Hummels, David (1993). "Gender Effects in Laboratory Public Goods Contribution: Do Individuals Put Their Money Where Their Mouth Is?" Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 22(3), pp. 255-67. Buchan, Nancy; Croson, Rachel and Solnick, Sara J. (2003). "Trust and Gender in the Investment Game," Mimeo. University of Wisconsin. Carpenter, Jeffrey; Holmes, Jessica and Matthews, Peter Hans (2004). "Charity Auctions: A Field Experimental Investigation." Mimeo, Middlebury College. Cialdini, Robert G. and Goldstein, Noah J. (2004). "Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity." Annual Review of Psychology 55, pp. 591-621. Conlin, Michael; Lynn, Michael and O'Donoghue, Ted (2003). "The Norm of Restaurant Tipping." Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 52(3), pp. 297-321. Cox, James C. and Deck, Cary A. (2002). "When Are Women More Generous Than Men?," Mimeo. Department of Economics, University of Arizona. Croson, Rachel and Buchan, Nancy (1999). "Gender and Culture: International Experimental Evidence from Trust Games." American Economic Review (Papers & Proceedings) 89(2), pp. 386-91. Croson, Rachel and Gneezy, Uri (2005). "Gender Differences in Preferences." Mimeo, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Cross, Susan E. and Madson, Laura (1997). "Models of the Self: Self-Construals and Gender." Psychological Bulletin 122(1), pp. 5-37. Eagly, Alice H. (1978). "Sex Differences in Influenceability." Psychological Bulletin 85(1), pp. 86116. Eagly, Alice H. and Carli, Linda L. (1981). "Sex of Researchers and Sex-Typed Communications as Determinants of Sex Difference in Influenceability: A Meta-Analysis of Social Influence Studies." Psychological Bulletin 90(1), pp. 1-20. Eagly, Alice H. and Chrvala, Carole (1986). "Sex Differences in Conformity: Status and Gender Role Interpretations." Psychology of Women Quarterly 10, pp. 203-20. 13 Eagly, Alice H. and Crowley, Maureen (1986). "Gender and Helping Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Social Psychological Literature." Psychological Bulletin 100(3), pp. 283-308. Eckel, Catherine C. and Grossman, Philip J. (1996). "The Relative Price of Fairness: Gender Differences in a Punishment Game." Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 30(2), pp. 143-58. ____ (1997). "Are Women Less Selfish Than Men? Evidence from Dictator Experiments." Economic Journal 108(448), pp. 726-35. ____ (2001). "Differences in the Economic Decisions of Men and Women: Experimental Evidence," C. R. Plott and V. L. Smith, Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland, forthcoming. ____ (2003). "Rebate Versus Matching: Does How We Subsidize Charitable Giving Matter?" Journal of Public Economics 87, pp. 681-701. ____ (2005). "Subsidizing Charitable Contributions: A Field Test Comparing Matching and Rebate Subsidies." Mimeo, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Station University. Falk, Armin (2004). "Charitable Giving as a Gift Exchange: Evidence from a Field Experiment." Working Paper Series, Institute for Empirical Research in Economics. University of Zurich. Fischbacher, Urs; Gächter, Simon and Fehr, Ernst (2001). "Are People Conditionally Cooperative? Evidence from a Public Goods Experiment." Economics Letters 71(3), pp. 397-404. Frey, Bruno S. and Meier, Stephan (2004a). "Pro-Social Behavior in a Natural Setting." Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 54, pp. 65-88. ____ (2004b). "Social Comparisons and Pro-Social Behavior: Testing Conditional Cooperation in a Field Experiment." American Economic Review 94(5), pp. 1717-22. Gabriel, Shira and Gardner, Wendi L. (1999). "Are There "His" and "Hers" Types of Interdependence? The Implications of Gender Differences in Collective Versus Relational Interdependence for Affect, Behavior, and Cognition." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77(3), pp. 642-55. Keser, Claudia and van Winden, Frans (2000). "Conditional Cooperation and Voluntary Contributions to Public Goods." Scandinavian Journal of Economics 102(1), pp. 23-39. List, John A. and Rondeau, Daniel (2003). "The Impact of Challenge Gifts on Charitable Giving: An Experimental Investigation." Economics Letters 79(2), pp. 153-59. Meier, Stephan (2005a). "Do Subsidies Increase Charitable Giving in the Long Run? Matching Donations in a Field Experiment," Mimeo. Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich. ____ (2005b). "Does Framing Matter for Conditional Cooperation?" Mimeo, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Potters, Jan; Sefton, Martin and Vesterlund, Lise (2004). "After You - Endogenous Sequencing in Voluntary Contribution Games." Journal of Public Economics, Forthcoming. Schubert, Renate; Brown, Martin; Gysler, Matthias and Brachinger, Hans Wolfgang (1999). "Financial Decision-Making: Are Women Really More Risk-Averse?" American Economic Review (Papers & Proceedings) 89(2), pp. 381-85. Seguino, Stephanie; Stevens, Thomas and Lutz, Mark A. (1996). "Gender and Cooperative Behavior: Economic Man Rides Alone." Feminist Economics 2(1), pp. 1-21. Shang, Jen and Croson, Rachel (2005a). "Field Experiments in Charitable Contribution: The Impact of Social Influence on the Voluntary Provision of Public Goods." Mimeo, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. ____ (2005b). "The Impact of Social Influence on the Voluntary Provision of Public Goods." Mimeo, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Sobel, Joel (2002). "Can We Trust Social Capital?" Journal of Economic Literature 40(1), pp. 139-54. 14 Solnick, Sara J. (2001). "Gender Differences in the Ultimatum Game." Economic Inquiry 39(2), pp. 189-200. Swamy, Anand; Knack, Stephen; Lee, Young and Azfar, Omar (2001). "Gender and Corruption." Journal of Development Economics 64(1), pp. 25-55. Vesterlund, Lise (2003). "The Informational Value of Sequential Fundraising." Journal of Public Economics 87(3-4), pp. 627-57. 15 Table 1 Summary Statistics for (Experimental) Semester Control group Field Experiment ‘Matching Donations M25% M50% Men Women Men Women Men Women Age 28.16 28.34 28.43 28.54 28.56 27.51 (6.97) (7.68) (8.05) (7.48) (8.00) (7.50) 11.70 10.99 11.89 10.80 # of semesters 12.37 11.42 (8.73) (8.18) (9.13) (7.42) (8.14) (6.66) Ph.D. 0.20 0.15 0.18 0.16 0.18 0.14 Nationality 0.11 0.12 0.14 0.11 0.11 0.08 Economist 0.15 0.06 0.14 0.05 0.14 0.10 Married 0.10 0.13 0.14 0.11 0.16 0.10 Past 8.42 8.32 7.82 8.23 8.33 8.35 donations (4.63) (4.59) (4.94) (4.57) (4.52) (4.56) Observations 5223 5624 125 140 133 134 Notes: standard errors in parentheses. Field Experiment ‘Social Comparison’ Low High Men Women Men Women 27.33 28.41 27.50 27.91 (5.82) (7.55) (7.05) (6.57) 11.32 11.48 11.71 11.35 (7.88) (8.66) (8.00) (7.95) 0.20 0.13 0.15 0.13 0.11 0.13 0.10 0.12 0.15 0.05 0.17 0.06 0.08 0.14 0.08 0.11 8.50 8.50 8.58 8.31 (4.64) (4.57) (4.61) (4.59) 424 452 445 433 Table 2 Contributions of Men and Women to the Two Funds Contribution to … Men Women Total No contribution at all (CHF 0) 27.88 28.03 27.96 Only foreigner fund (CHF 7) 3.38 4.26 3.84 Only loan fund (CHF 5) 2.55 3.10 2.83 Contribution to both funds (CHF 12) 66.18 64.61 65.37 100 100 100 47,185 50,489 97,674 # of observations Pearson χ2(3)= 84.5829; Pr = 0.000 16 Table 3 Multivariate Regression Analysis of Gender Differences Gender (female=1) # of semesters # of semesters2 Age Age2/100 Foreigner (=1) Married (=1) Freshmen (=1) Main stage (=1) Ph.D. (=1) Economics major Period dummies Constant # of observations Log likelihood Panel I Coeff. z-value Panel II Coeff. t-value -0.062 -0.044 0.001 0.024 -0.003 -0.059 0.064 -0.072 0.122 -0.021 -0.167 Yes 0.175 2.98** 97,674 -56990.18 -0.329 -0.171 0.002 0.086 -0.010 -0.637 0.172 -0.426 0.504 -0.083 -0.697 Yes 6.777 97,674 Marg. Effect -2.96** -2.07% -10.36** -1.48% 5.63** 0.02% 9.37** 0.79% -10.00** -0.001% -1.86 -1.98% 1.77 2.10% -2.93** -2.44% 5.53** 4.10% -0.56 -0.70% -5.02** -5.79% -3.94** -10.76** 6.01** 10.77** -11.70** -4.83** 1.21 -4.49** 5.85** -0.54 -4.95** 34.17** Notes: Panel I presents a probit analysis. Dichotomous dependent variable: contribution to at least one fund (=1). Panel II presents an OLS analysis. Dependent variable: donations in CHF. Both models are estimated with robust standard errors and clustering on the individual level. Level of significance: *0.01<p<0.05, ** p<0.01 17 Table 4: Gender and Matching Donations Dichotomous dependent variable: Contribution to both funds (=1) Panel I Panel II Coefficient Coefficient (z-value) (z-value) Treatment “Matching 25%” Treatment “Matching 50%” 0.265 (1.23) 0.454* (2.09) Gender * “Matching 25%” Gender * “Matching 50%” Individual fixed effects Semester dummies # of observations # of individuals Log likelihood included included 37,134 5,377 -14020.231 0.141 (0.42) 0.454 (1.42) 0.205 (0.47) 0.001 (0.00) included included 37,134 5,377 -14020.119 Notes: Logit models. Level of significance: *0.01<p<0.05, ** p<0.01 Table 5: Gender and Social Comparisons Dichotomous dependent variable: Contribution to at least one fund (=1) Coefficient P>|z| (z-value) Treatment “High” (64%) Treatment “Low” (46%) Gender*Treatment “High” Gender* Treatment “Low” Individual fixed effects Semester dummies N Log likelihood 0.722 (3.68**) -0.074 (-0.39 -0.586 (-2.24*) 0.111 (0.43) included included 36,113 -13621.33 0.000 0.694 0.025 0.664 Notes: Logit model. Level of significance: *0.01<p<0.05, ** p<0.01 18 Figure 1: Gender and Matching Donations Proportion contributing to both funds 0.72 0.7 0.68 Men Women 0.66 0.64 0.62 Control group Matching '25%' Matching '50%' Treatment groups Proportion who contributes to at least one fund Figure 2: Gender and Social Comparison 82% 80% 78% 76% Men Women 74% 72% 70% Control group Treatment 'Low' Treatment 'High' Treatment groups 19