Smithfield Foods Case

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

C A S E 31

Smithfield Foods

When Growing the Business Damages the Environment

LaRue T. Hosmer

The University of Alabama

C-568

Smithfield

Foods was the largest hog producer and pork processor in the world, the company’s fiscal 2002 output included

5.1 billion pounds of chops, roasts, ribs, loins, ground pork, bacon, hams, sausages, and sliced deli meats. Smithfield supplied both food-service wholesalers and grocery retailers, and its family of brands included some of the most popular pork brands in the world

(see Exhibit 1). Smithfield Foods’ fresh pork and processed meats products were sold in

North America and more than 25 other global markets.The company was vertically integrated, with operations in hog farming, feed mills, packing plants, and distribution.

In 1998, Smithfield Foods began expanding into foreign markets, making acquisitions in Canada, France, and Poland. In August 1999, the company further developed its international operations through a 50-percent-owned integrated joint venture in

Mexico. Management believed these acquisitions gave the company strong market positions, high-quality manufacturing facilities, and excellent growth potential in regions that had high pork consumption levels. Smithfield Foods owned and operated hog farms with about 700,000 sows in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Utah, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Missouri, Illinois, Mexico, Brazil, and Poland.

The company raised 12 million hogs in 2001, roughly 3.5 times the number of its nearest U.S. competitor. Smithfield’s hog farming subsidiary, Murphy-Brown LLC, owned

700,000 U.S. sows plus an interest in another 40,000 in Mexico, Brazil, and Poland. It specialized in producing exceptionally lean hogs; the company’s own special breed of

SPG sows, a consistent raw material for branded Smithfield Lean Generation Pork, accounted for approximately 55 percent of the total herd.

The company was headquartered in Smithfield, Virginia, and a big fraction of the company’s operations were in North Carolina—Smithfield’s biggest pork processing plant was in Bladen County, North Carolina, and many of its hog farming operations were in eastern North Carolina. Smithfield’s southern base provided low wages and relatively low operating costs across much of its integrated operations, factors that helped pave the way for Smithfield’s competitive prices and strong growth. The company’s longtime chairman and CEO, Joseph W. Luter III, continually emphasized the need to drive down costs and push up sales. In 2002, the company’s sales were 6.6 times 1993 levels and net income was almost 50 times greater (see Exhibit 2). Top executives at

Smithfield Foods wanted to continue the company’s rapid and profitable expansion and were constantly on the lookout for opportunities to grow the company’s business.

Professor Hosmer holds the Durr-Fillauer Chair in Business Ethics at The University of Alabama. Copyright

© by LaRue T. Hosmer.

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods

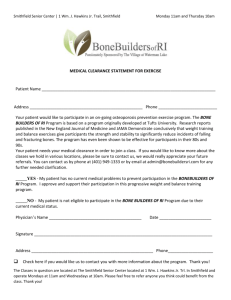

Exhibit 1 Smithfield’s Family of Meat Brands and Products, 2002

C569

Opposition to Smithfield’s Expansion

Over the last decade, Smithfield Foods had met with mounting opposition to expansion of its business, particularly the hog farming aspect. The company owned or leased numerous hog production facilities, primarily in North Carolina, Utah, and Virginia, with additional hog production facilities in Colorado, South Carolina, Illinois, Texas, and

Oklahoma. One of the chief pockets of opposition to Smithfield’s hog farming activities came from rural residents in eastern North Carolina, where there were some 8,000 hog farms. Neighboring residents complained that commercial hog farming had essentially been imposed on them and that it entailed substantial adverse impacts in the form of low wages and environmental discharges.

Eastern North Carolina and Smithfield’s Hog

Farming Operations

Eastern North Carolina, essentially the area extending about 150 miles from Raleigh

(the state capital) to the Atlantic coast, is a region of flat land, sandy soil, and ample rainfall. At one time it was a relatively prosperous region, with thousands of small family farms, each of which had a tobacco allotment. During the 1930s far more tobacco had been grown than was needed, and the price plummeted. One of the governmental initiatives of the Depression era was a restriction on the total amount of tobacco that could be grown, and this total amount was divided up among the existing growers by restricting each to a set percentage of the amount of their land that had been devoted to the crop during a given base year. These restrictions on growth first stabilized and latter increased the price, and the possession of an allotment almost guaranteed the financial prosperity of the farm.

The typical family farm would have 150 to 200 acres. Perhaps 15 acres would be devoted to tobacco, and the balance would be sown in corn, wheat, rye, or soybeans, or left as pasture for cattle or—more frequently—hogs. The grains grown locally would be trucked to the nearest town within the region to be milled into feed and then returned to the farm for the livestock. The cattle and hogs produced locally would be trucked to the nearest town to be sold at auction, and then slaughtered and processed at a nearby packing plant. These towns were also relatively prosperous, as the farmers

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C570 PART FIVE Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

Exhibit 2 SMITHFIELD FOODS, FINANCIAL SUMMARY, 1995–2002 (DOLLARS AND

SHARES IN THOUSANDS, EXCEPT PER SHARE DATA)

2002 2001

Fiscal Years

1999 1997 1995

Operations

Sales

Gross profit

Selling, general and administrative expenses

Interest expense

Income from continuing operations before change in accounting for income taxes

Income (loss) from discontinued operations

Change in accounting for income taxes

Net income

$7,356,119

1,092,928

543,952

94,326

196,886

—

—

196,886

$5,899,927

948,903

450,965

88,974

223,513

—

—

223,513

$3,774,989

539,575

295,610

40,521

94,884

—

—

94,884

$3,870,611

323,795

191,225

26,211

44,937

—

—

44,937

$1,526,518

146,275

61,723

14,054

31,915

(4,075)

—

27,840

Per Diluted Share

Income from continuing operations before change in accounting principle for income taxes

Income (loss) from discontinued operations

Change in accounting for income taxes

Net income

Weighted average shares outstanding

Financial Position

$1.78

—

—

$1.78

110,419

Total assets

Long-term debt and capital lease obligations

Shareholders’ equity

Financial Ratios

Current ratio

Long-term debt to total capitalization

Return on average shareholders’ equity a,b

Other Information

Capital expenditures c

Depreciation expense

Number of employees

$ 798,426

3,877,998

1,387,147

1,362,774

2.11

50.4%

16.2%

$171,010

139,942

—

$2.03

—

—

$2.03

110,146

$ 635,413

3,250,888

1,146,223

1,053,132

2.01

52.1%

18.4%

$144,120

124,836

34,000

$1.16

—

—

$1.16

81,924

$ 215,865

1,771,614

594,241

542,246

1.46

52.3%

21.0%

$95,447

63,524

33,000

$.57

—

—

$.57

77,116

$ 164,312

995,254

288,486

307,486

1.51

48.4%

15.9%

$69,147

35,825

17,500

$.46

(.12)

—

$.46

67,846

$ 60,911

550,225

155,047

184,015

1.35

44.4%

18.4%

$90,550

19,717

9,000 a Computed using income from continuing operations before change in accounting principle.

b The fiscal 2002 computation excludes a gain on the sale of IBP, Inc. common stock and a loss as a result of a fire at a hog farm.

c The fiscal 2001 computation excludes gains from the sale of IBP, Inc. common stock, less related expenses, and the sale of a plant.

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods and their families purchased clothing and household goods at local stores and automobiles and farm machinery at local dealers.

This prosperity started downhill in the 1970s as the national campaigns against smoking led to continual reductions in the size, and consequently the profitability, of the tobacco allotments, which eventually came almost to an end. Local prosperity continued to decline in the 1980s as very large feed lots in Nebraska, Iowa, and Kansas developed a much less costly means of raising hogs prior to slaughter; the piglets spent only the first 12 to 15 months of their lives on the farms where they were bred before being brought to fenced open-air corrals where they were closely confined but fed continuously to gain weight. Farmers in eastern North Carolina had to compete against this new and far more efficient production process. Prices for the hogs raised in eastern North Carolina declined sharply, and many of the local packing plants went out of business.

Local prosperity stabilized to some extent in the 1990s, though with a greatly changed distribution of income, as Smithfield Foods introduced the concept of the factory farm. Large metal sheds with concrete floors were built, each designed to hold up to 1,000 hogs. Feeding was by means of a mechanized conveyor that carried food alongside both walls. Waste was removed by hosing it off the floors to a central trough that carried it to a storage lagoon. Temperature was controlled by huge fans at each end of each shed. Every effort was made to reduce costs. Feed grains were no longer grown, purchased, and milled locally; instead most grains were grown, purchased, and milled in the Midwest and transported to eastern North Carolina by unit feed trains, which were strings of covered hopper cars that moved as a unit, without switching, from the feed mill in Nebraska or Iowa directly to one of the company’s distribution centers in North Carolina. Some feed grains were grown and purchased even more cheaply abroad, primarily in Australia and Argentina, and then carried by ship to a company-leased milling facility and distribution center in Wilmington (a port in southeastern North Carolina, near the South Carolina border).

Limited farm machinery was needed for this new method of raising hogs, given that few feed grains were grown locally, but the little that was needed was purchased by the Smithfield headquarters office directly from the manufacturer. Many farm equipment dealers within the region were forced to close. Even diesel fuel, needed for the trucks that transported the feed grains to the farms and the mature hogs to the packing plants, was purchased from the refinery, transported by railway tank cars to large storage tanks at the distribution centers, and pumped directly into the trucks. Local fuel dealers got little or none of this business. All truck purchases were arranged by bid from national dealers located in Detroit (auto companies had refused to sell outside their dealer chains, but they allegedly gave favored prices to very large dealers near their corporate headquarters) at very low prices, and all subsequent truck repairs were done at company-owned repair shops located at the company-owned distribution centers. Some truck dealers in the region were forced to close.

Executives at Smithfield Foods did not apologize for the business model that they had created. Their attitude could be summed up as follows: “This is the way the world is going and this is what the market demands. All we have done is to create a competitive system that works. Moreover, we have saved farms and brought jobs to the eastern North Carolina region through this system, and we have provided better (leaner) pork products at lower prices to our customers.” Smithfield’s development of a “competitive system that works” had won Joseph Luter an award as Master Entrepreneur of the Year in 2002; a Smithfield news release dated December 21, 2002, said:

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C571

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

C572

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

PART FIVE Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

Joseph W. Luter III has been named the Ernst & Young 2002 Virginia Master

Entrepreneur of the Year. The Ernst &Young program recognizes entrepreneurs who have demonstrated excellence and extraordinary success in such areas as innovation, financial performance and personal commitment to their businesses and communities. . . .

Since becoming chairman and chief executive officer of Smithfield Foods,

Inc. in 1975, Mr. Luter transformed the company from a small, regional meat packer with sales of $125 million and net worth of $1 million to an international concern with annual sales of $8 billion and a net worth of $1.4 billion.

Smithfield Foods did not own the farms that raised the hogs. Instead, company representatives would select a reasonably large farm, one that had been successful in the past and therefore was financially solvent now, and negotiate a contract with the owning family to raise hogs at a set price per animal. The farm family would, frequently using a loan provided through the Smithfield Corporation and a contractor licensed by the Smithfield Corporation, build the metal barns with concrete floors, feed conveyors, ventilation fans, and waste systems; connect the waste systems to storage lagoons (five to eight acres in size); construct feed bins and loading ramps; and be ready for business. Smithfield Corporation would then deliver the hogs at piglet stage, provide a constant supply of feed grains mixed with antibiotics (to prevent disease in the crowded conditions of the metal barns), and offer free veterinarian service. The responsibility of the farm family was to raise those hogs to marketable weight as quickly and as efficiently as possible. This was termed contract farming; it was described in the following terms in five-part investigative series that ran February 19–26, 1995, in the Raleigh News and Observer:

Greg Stephens is the 1995 version of the North Carolina hog farmer. He owns no hogs. Stephens carries a mortgage on four new confinement barns that cost him $300,000 to build. The 4,000 hogs inside belong to a company called

Prestage Farms, Inc. (one of the larger suppliers of Smithfield Foods). Prestage simply pays Stephens a fee to raise them. . . .

This arrangement is called contract farming, and it’s hardly risk-free. But for anyone wanting to break into the swine business these days, it’s the only game in town. “Without a contract, there’s no way I’d be raising hogs,” says

Stephens, “and even if I had somehow gotten in, my pockets aren’t nearly deep enough to let me stay in.”

Welcome to corporate livestock production, the force behind the swine industry’s explosive growth in North Carolina. The backbone of the new system is a network of hundreds of contractors like Stephens, the franchise owners in a system that more closely resembles a fast-food chain than traditional agriculture.

Nowhere in the nation has this change been as dramatic, or as officially embraced, as in North Carolina. As a result, the hog population has more than doubled in four years, and nearly all of that growth has occurred on farms controlled by the big companies. Meanwhile, independent farmers have left the business by the thousands.

In 1998 Smithfield Foods reportedly had a two-year waiting list of farmers wishing to obtain hog farming contracts. Industry observers, however, worried about the practice of saddling hundreds of small farmers with thousands of dollars of debt. As one elected state representative said, “Why invest your capital when you can get a farmer to take the risk? Why own the farm when you can own the farmer?” 1

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods

The problem foreseen by industry observers was the possibility that a company could cancel its contract with only 30 days’ notice, leaving the farmer with the debt and no income to repay it, or could threaten to cancel and then renew the contract only with a sharply lower price per animal. Both sudden cancellations and lower prices were said to have happened frequently in the poultry industry:

The changes that are sweeping the swine industry today were pioneered by chicken and turkey growers in the 1960s and ’70s. Total confinement housing, vertical integration, and contract farming are all standard practices in the feather world. As a result, you need only look at chickens to see where pork is headed.

The poultry industry today is fully integrated—meaning a handful of companies control all phases of production—and the labor is performed by an army of contract growers, some of them decidedly unhappy. “It’s sharecropping, that’s what it is,” said Larry Holder, a chicken farmer and president of the Contract Poultry Growers Association.

The Raleigh News and Observer interviewed a number of farmers with hoggrowing contracts in North Carolina. One farmer with 10 years of experience growing for Carroll Farms (another large supplier of Smithfield Foods), said, “They’ve been nothing but good to me.” 2 Greg Stephens, the farmer quoted earlier, told the News and

Observer that in his case the biggest selling point had been his freedom from market risk: “If hog prices go south, as they did two months ago, the contact farmer is barely affected. The company that owns the pigs takes on more risk than you do.” 3

The survival of over 1,000 family farms as contract hog growers is cited as one of the major benefits of the industrialization of agriculture in eastern North Carolina. Another is the creation of new agricultural jobs. Each of the contract farms averages 7,500 animals. The owning families cannot care for all those animals, even though the hogs are closely confined and automatically fed and watered. The typical farm will employ five people from the community at wages of $7 to $8 an hour; working conditions are hard and unpleasant. Most of the people filling such jobs are untrained and poorly educated area residents.

Smithfield’s two new slaughterhouses in North Carolina employed about 3,000 people. These jobs were also regarded as hard and unpleasant jobs, some of which involved killing and disemboweling the hogs. The killing was said to be painless, and much of the early processing (scraping the carcass to remove the hair, and dealing with the internal organs) was automated. One of the more labor-intensive tasks involved preparing cuts of meat for packaged sale at grocery chains. Most grocery chains, to reduce their internal costs, had eliminated the position of store butchers, opting instead to buy their fresh meats cut, wrapped, packaged, and ready for sale. The cutting at meatpacking facilities was done on a high-speed assembly line, using very sharp laser-guided knives; workers were under continual pressure to perform and were exposed to dangers of injury. Workers who became skilled at this cutting and were able to endure the stress earned $10 to

$12 an hour; turnover was relatively high because of the strenuous job demands. Many of the workers at the high-volume packing plants in eastern North Carolina were immigrants from Central or South America. The jobs were described in the following terms by an undercover reporter for the New York Times who worked at one of the Smithfield packing plants for three weeks on what was termed the picnic line:

One o’clock means it is getting near the end of the workday [for the first shift].

Quota has to be met, and the workload doubles. The conveyor belt always overflows with meat around 1 o’clock. So the workers redouble their pace, hacking

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C573

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

C574

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

PART FIVE Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy pork from shoulder bones with a driven single-mindedness. They stare blankly, like mules in wooden blinders, as the butchered slabs pass by.

It is called the picnic line: 18 workers lined up on both sides of a belt, carving meat from bone. Up to 16 million shoulders a year come down that line here at Smithfield Packing Co., the largest pork production plant in the world. That works out to about 32,000 per shift, 63 a minute, one every 17 seconds for each worker for eight and a half hours a day. The first time you stare down at that belt you know your body is going to give in way before the machine ever will.

4

The vertical integration of the industry, which has resulted in very limited purchasing of feed, machinery, and fuel from local sources; the debt-laden nature of the farm contracts, which have brought concerns about the possibility of future contract cancellations or price reductions; and the low-pay/low-quality nature of the jobs that have been created at both the farms and the packing plants had all combined to create popular opposition to any planned expansion of Smithfield Foods within eastern North

Carolina. A much bigger and far more intense issue, however, was the alleged impact of hog farming on the environment:

Imagine a city as big as New York suddenly grafted onto North Carolina’s

Coastal Plain. Double it. Now imagine that this city has no sewage treatment plants. All the wastes from 15 million inhabitants are simply flushed into open pits and sprayed onto fields.

Turn those humans into hogs, and you don’t have to imagine at all. It’s already here. A vast city of swine has risen practically overnight in the counties east of Interstate 95. It’s a megalopolis of 7 million animals that live in metal confinement barns and produce two to four times as much waste, per hog, as the average human.

All that manure—about 9.5 million tons a year—is stored in thousands of earthen pits called lagoons, where it is decomposed and sprayed or spread on crop lands. The lagoon system is the source of most hog farm odor, but industry officials say it’s a proven and effective way to keep harmful chemicals and bacteria out of water supplies. New evidence says otherwise:

■ The News and Observer has obtained new scientific studies showing that contaminants from hog lagoons are getting into groundwater. One N.C. State

■

■

University report estimates that as many as half of existing lagoons—perhaps hundreds—are leaking badly enough to contaminate groundwater.

The industry also is running out of places to spread or spray the waste from lagoons. On paper, the state’s biggest swine counties already are producing more phosphorous-rich manure than available land can absorb, state Agriculture Department records show.

Scientists are discovering that hog farms emit large amounts of ammonia gas, which returns to earth in rain. The ammonia is believed to be contributing to an explosion of algae growth that’s choking many of the state’s rivers and estuaries.

5

Raising hogs is admitted even by farm families to be a messy and smelly business.

Hogs eat more than other farm animals, and they excrete more. And those excretions smell far, far worse. Having 50 to 100 hogs running free in a fenced pasture is one thing. The odor is clearly noticeable, but that sharp and pungent smell is felt to be part of rural living. Having 5,000 to 10,000 hogs closely confined in metal barns, with large ventilation fans moving the air continually from each barn, and the wastes from those

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods hogs collected in huge open-air lagoons is something else. People who live near one of the large hog farms say that, unless you’ve experienced it, you just can’t know what it is like:

At 11 o’clock sharp on a Sunday morning the choir marched into the sanctuary of New Brown’s Chapel Baptist Church. And the stench of 4,800 hogs rolled right in with them.

The odor hung oppressively in the vestibule, clinging to church robes, winter coats and fancy hats. It sent stragglers scurrying indoors from the parking lot, some holding their noses. Sherry Leveston, 4, pulled her fancy white sweater over her face as she ran. “It stinks,” she cried.

It was another Sunday morning in Brownsville, a Greene County North

Carolina hamlet that’s home to 200 people and one hog farm. Like many of its counterparts throughout the eastern portion of the state, the town hasn’t been the same since the hogs moved in a couple of years ago.

To some, each new gust from the south [the direction of the farm] is a reminder of serious wrongs committed for which there has been no redress.

“We’ve basically given up,” said the Rev. Charles White, pastor at New

Brown’s Chapel.

In scores of rural neighborhoods down east [the eastern portion of North

Carolina] the talk is the same. There’s something new in the air, and people are furious about it.

Hog odor is by far the most emotional issue facing the pork industry—and the most divisive. Growers assert their right to earn a living; neighbors say they have a right to odor-free air. Hog company officials, meanwhile, accuse activists of exaggerating the problem to stir up opposition. . . .

For other residents [of Brownsville, close to New Brown’s Chapel] hog odor has simply become an inescapable part of their daily routine. It’s usually heaviest about 5

A

.

M

., when Lisa Hines leaves the house for her factory job. It seeps into her car and follows her on her commute to work. It clings to her hair and clothes during the day. And it awaits her when she returns home in the afternoon.

“It makes me so mad,” she said. “The owner lives miles away from here, and he can go home and smell apples and cinnamon if he wants to. But we have no choice.” 6

The 7 million hogs in eastern North Carolina currently generated about 9.5 million tons of manure each year. This waste was stored in large earthen pits called lagoons.

These pits were open so that sunlight would decompose the wastes and kill the harmful bacteria; the manure was then spread on farm fields as organic fertilizer. This had been the accepted means for disposing of animal wastes on small family farms for centuries. It was a method fully protected by federal, state, and local laws; a hog farmer—whether a small family or large contract farm—could not be sued for any inconveniences brought about by the hogs, unless those inconveniences were the result of clear negligence in caring for the hogs.

Exhibit 3 describes the environmental improvement projects the company had under way in 2001 and Exhibit 4 presents Smithfield Foods’ environmental policy statement.

The difference now, of course, comes from the huge expansion of scale. Again, the wastes of 50 to 100 animals were easily accommodated. There was a noticeable effect on air quality, but that was felt to be a natural consequence of living in the country, and the smell came from your own farm, or that of your neighbor, or that of a person who

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C575

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C576 PART FIVE Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

Exhibit 3 SMITHFIELD FOODS’ ENVIRONMENTAL PROJECTS IN 2001

Environmental Project Project Description Project Background

Smithfield Packing Company’s processing plant in Kinston, NC, began installing three cooling towers capable of recirculating more than 200,000 gallons of water daily.

“Since the cooling towers went online The city’s water usage had taxed the in February 2001, the Kinston plant has area aquifer. Smithfield’s plant reduced its monthly groundwater use handles vacuum packaging, a process by 5 million gallons. That puts less that requires approximately 200,000 demand on an already stressed water gallons of cooling water daily. In table, improving the quality of life for addition to Kinston, Smithfield has the people living here.” —Bill Gill, implemented similar water assistant vice president, environmental conservation systems at facilities affairs, Smithfield Foods.

in Smithfield and Portsmouth, VA, and in Wilson, NC.

In 1997, Smithfield Packing “The plant successfully expanded As early as 1995, Smithfield Packing

Company’s Tar Heel, NC, plant, the production while reducing the overall began seeking a way to increase world’s largest pork processing need for groundwater and, in addition, production at the Tar Heel plant facility, introduced a state-of-the-art decreased the volume of treated water without exceeding North Carolina water treatment and reuse system.

discharged to the Cape Fear River. limits on the characteristics of its

This waste treatment system is a model wastewater and without increasing for industry. It is a typical example of the impact on marine life in the our continued commitment to protect Cape Fear River. Smithfield invested and preserve the environment.” $3 million to augment existing water

—Robert F. Urell, vice president, treatment efforts with a system that corporate engineering and chairman, allows the plant to reuse an average environmental compliance committee, of 1 million gallons daily.

Smithfield Foods.

In March 2001, Carroll’s Foods, part “ISO certification is the gold standard As early as 1997, Carroll’s began of Smithfield Foods’ Murphy-Brown, for environmental excellence. It means developing an environmental

LLC, subsidiary, became the world’s that Carroll’s has clearly-defined management system that could meet first agricultural livestock company methods for monitoring and measuring the stringent certification to receive ISO 14001 certification for the environmental impact of its requirements of the Geneva-based environmental management systems on its farms in North

Carolina, South Carolina, and

Virginia.

activities and in identifying potential problems. This should assure residents Standardization (www.iso.org). Sister of all three states that we’ve really taken the lead in protecting their interests.” —Don Butler, director of governmental relations and public affairs, Murphy-Brown.

International Organization for companies Murphy Farms and

Brown’s of Carolina expect to receive

ISO certification for their North

Carolina farms by the end of 2001, with their western farming operations to be certified in 2002. Over the next

24 months, Smithfield will expand its

EMS efforts and seek ISO certification for all of the company’s North

American meat processing operations.

John Morrell’s processing facility in Sioux Falls, SD, and Smithfield

“We are using a cleaner-burning alternative to oil or natural gas while

In treating wastewater, both facilities use anaerobic lagoons that generate

Packing Company’s Tar Heel, NC, also reducing emissions of methane, methane as a by-product. Since it plant have modified their boilers to an odorous greenhouse gas. In Sioux opened in 1992, the Tar Heel plant burn methane biogas as an alternative fuel.

Falls, we recovered 125 million cubic has captured much of this biogas feet of methane gas in 2000 and expect and diverted it to a recovery boiler.

to reduce emissions by 1,400 tons The plant brought a second boiler onannually. That has positively impacted line in 2001. John Morrell’s Sioux air quality throughout the area, including Sioux Falls Park adjacent to the plant.” —Dennis Dykstra, utilities engineer at the Sioux Falls plant.

Falls boiler went live in 2000.

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods C577

Exhibit 3 Continued

Environmental Project Project Description Project Background

Funded in part by a $15 million “We could see potentially cleaner air Smithfield Foods helped pioneer two contribution from Smithfield Foods, through the reduction of methane and of the solutions currently under

North Carolina State University ammonia emissions generated by consideration—BEST (Biomass

(NCSU) is investigating 18 different lagoons. We expect to make our final Energy Sustainable Technology) and technologies to modify or replace recommendation in 2003, and current methods of swine waste Smithfield Foods has agreed to apply

ISSUES (Innovative Sustainable

Systems Utilizing Economical disposal on hog farms.

the technologies we select, if commercially feasible, on all its company-owned farms.” —Mike

Williams, PhD, director of the NCSU

Solutions). BEST, in development since 1995, removes the solids from farm wastewater for conversion into green energy such as steam or

Animal and Poultry Waste Management electricity. ISSUES is a series of

Center and project head.

technologies that enhance the performance of existing lagoons.

NCSU has paired ISSUES with a technology that utilizes methane in a microturbine. This combined solution harvests the energy value of hog manure to create green electricity.

In August 2000, Smithfield Foods pledged $50 million ($2 million annually over 25 years) to North

Carolina to aid in the state’s environmental efforts. Smithfield also committed resources and manpower to help preserve the

Albermarle-Pamlico estuary.

“If the state uses our contribution to

Poulson, vice president and senior advisor to the chairman, Smithfield

Foods.

To date, Smithfield Foods has purchase buffer lands and conservation donated $4 million to North Carolina easements, it would offer North and is enthused about specific

Carolina’s waterways additional protection from development and projects to be undertaken with this money. The Albemarle-Pamlico storm water runoff. As for this estuary, Sounds, the second largest estuarine protecting its fragile ecosystem is complex in the United States, critical because it is vital for commercial fishing.” —Richard currently suffer from stream bank erosion, sedimentation, and nutrient loading.

Murphy Brown, Smithfield Foods’ The effects of the program will be far The land management program gives hog farming subsidiary, is finalizing reaching. For example, it will conserve equal consideration to water quality plans for an integrated land management program. It will woodlands and ensure the continued biological diversity of wetlands and protection, soil conservation, and wildlife habitat development. It ensure the sound stewardship of all other ecologically sensitive areas. The applies equally to lands normally lands on more than 200 companynesting grounds of a number of outside the scope of state agricultural owned and operated farms in North species will be protected as will areas regulation. Stewardship methods

Carolina.

containing mature longleaf pines, include sound irrigation, tillage, and mature bald cypress trees, and mature harvesting on spray fields, timber bottomland hardwoods.” —Jeff Turner, management, and conservation vice president, environmental and government affairs, Murphy-Brown.

easements through an appropriate agency.

Source: www.smithfieldfoods.com, December 26, 2002.

had been there for years. There was a probable effect on water quality, but farm wells were always located uphill and a substantial distance from manure piles, and it was thought that neighbors would be protected by natural filtration through the clay subsoils of the region. No one worried very much about possible public health effects of small numbers of farm animals.

The wastes from 5,000 to 10,000 animals could not be so easily accommodated, and people did worry about the possible public health effects of very large numbers of

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

C578

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

PART FIVE Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

Exhibit 4 SMITHFIELD FOODS: ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY STATEMENT,

2002

It is the corporate policy of Smithfield Foods, Inc., and its subsidiaries to conduct business in an ethical manner consistent with continual improvement in regard to protecting human health and the environment. The following management principles are adopted to ensure this policy is endorsed and implemented throughout our organization:

1. Maintaining an effective organizational and accountability structure for environmental performance;

2. Establishing policies and practices for conducting operations in compliance with environmental laws, regulations, and other organizational policies;

3. Training and motivating facility operators to conduct all activities in an environmentally responsible manner;

4. Assessing the environmental impacts of changes in operations;

5. Encouraging the operation of facilities with diligent consideration to pollution prevention and the sustainable use/reuse of energy and materials;

6. Encouraging prompt reporting of any environmentally detrimental incidents to regulators and management;

7. Providing facility operators with information relating to specific local or regional conditions, current and/or proposed environmental regulations, technologies, and stakeholder expectations;

8. Providing for environmental performance goals, assessing performance, conducting audits, and sharing appropriate performance information throughout our organization;

9. Promoting the adoption of these principles by suppliers, consultants, and others acting on behalf of the company; and

10. Documenting development, implementation, and compliance efforts associated with these principles.

Source: www.smithfieldfoods.com, December 26, 2002.

farm animals. Debilitating asthma had become a much more frequent condition among young children who lived near large hog farms, and there was concern that waste was leaking from the lagoons and contaminating the ground water. The conventional wisdom about the lagoons was that the heavier sludge was supposed to settle on the bottom and form a seal that would prevent the escape of harmful bacteria or destructive chemicals:

As recently as two years ago, the U.S. Division of Environmental Management told state lawmakers in a briefing that lagoons effectively self-seal within months with “little or no groundwater contamination.” Wendell H. Murphy, a former state senator who was also [in partnership with Smithfield Corporation] the nation’s largest producer of hogs, said in an interview this month that “lagoons will seal themselves” and that “there is not one shred, not one piece of evidence anywhere in this nation that any groundwater is being contaminated by any hog lagoon.”

What Murphy didn’t know was that a series of brand-new studies, conducted among Eastern North Carolina hog farms, showed that large numbers of lagoons are leaking, some of them severely.

7

The Raleigh News and Observer had reported that researchers at North Carolina

State University had dug test wells near 11 lagoons that were at least seven years old.

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods

They found that more than half of the lagoons were leaking moderately to severely; even those lagoons that were described as leaking only moderately still produced groundwater nitrate levels up to three times the allowable limit. The researchers also found that lagoons were not the only source of groundwater contamination. They dug test wells and examined water quality in fields where hog waste had been sprayed as fertilizer, and found evidence of widespread bacterial and chemical contamination. It was felt that fully as much water contamination came from the practice of attempting to dispose of the decomposed waste through spraying on crops as from the earlier storage of decomposing waste in the lagoons. According to the Raleigh News and Observer reporter, too much waste was being sprayed on too few fields, even though almost all farmers in the region now accepted this natural fertilizer in lieu of buying commercial products.

The researchers from North Carolina State University, however, did not urge rural residents to rush out to buy bottled water. In most of the cases they concluded that the contaminants appeared to be migrating laterally toward the nearest ditch or stream, and they found no evidence that a private well had been contaminated. But they did find evidence that numerous streams had been contaminated, partially from leakage but primarily from spills and overflows:

Frequently major spills are cleaned up quickly so that the public never hears about them. That’s what happened in May 1995 when a 10-acre lagoon ruptured on Murphy’s Farms’ 8,000-hog facility in Magnolia, North Carolina. A limestone layer beneath the lagoon collapsed, sending tons of waste cascading into nearby Millers Creek in an accident that was never reported to state waterquality officials.

An employee of the town’s water department discovered the problem when he saw corn kernels and hog waste floating by in the creek that runs through the center of town. He alerted the company, and within hours a task force had been assembled to plug the leak.

It took four days to find the source and fix the problem. But neither Magnolia town officials nor Murphy Farms executives ever notified the state about the spill.

“In retrospect, maybe we should have,” Wendell Murphy said, “but I would also say that to my knowledge no harm has ever come of it.”

Former employees of hog companies, however, told News and Observer reporters that spills were a common occurrence. “Hardly a week goes by,” said a former manager for one of the largest hog farms in the state, “that there isn’t some sort of leak or overflow. Almost any heavy rain will bring an overflow.

When that happens, workers do the best they can to clean it up. After that it’s just pray no one notices and keep your mouth shut,” he explained.

8

The waste lagoons could not be covered with a roof to prevent overflows associated with heavy rains, or enclosed with a building to prevent the escape of odors; They were simply too large—five to eight acres—and it was necessary to have direct sunlight to create the natural conditions that would break down the toxic chemicals and kill the harmful bacteria in the wastes. Company officials seemed to believe that there was no possible solution to the problem of the extremely bad odors; essentially they said it would just be necessary for people to learn to live with the smell, which extends up to two miles from the open lagoons and the sprayed fields. According to the Raleigh

News and Observer ,

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C579

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

C580

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

PART FIVE Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

Wendell Murphy, chairman of Murphy Family Farms [part of the Murphy

Brown hog farming subsidiary of Smithfield Foods] said that while the hog industry is extremely sensitive to the odor problem, he thinks the industry’s economic importance should be considered in the equation. “Should we expect the odor to never drift off the site to a neighbor’s house? If so, then we’re out of business. We all have to have some inconvenience once in a while for the benefits that come with it.” 9

As the Raleigh News and Observer reported, feelings ran high among eastern

North Carolina residents in opposing further expansion of hog farming in the region:

Three weeks ago, the tiny town of Faison held a referendum of sorts on whether its residents wanted a new industrial plant, with 1,500 new jobs, built in their community. The jobs lost.

Because the industry in question was a hog-processing plant, people packed the local fire station an hour early to blast the idea. They jeered and hissed every time the county’s industrial recruiter mentioned pigs or the plant. “I want to know two things,” thundered one burly speaker thrusting a finger at that much smaller industrial recruiter, Woody Brinson, “How can we stop this thing, and how can we get you fired?”

The town council’s eventual 3–0 vote against the proposed IBP [a subsidiary of Smithfield Foods] hog slaughterhouse may have little effect on whether the plant is built. [Zoning within rural North Carolina is controlled by the county, not the municipality, and agriculturally related zoning has always been very loosely applied, to benefit local farmers.] What was striking about this meeting, and this vote, was that both occurred in the heart of Duplin

County, an economic showcase for the hog industry.

With a pigs-per-person ratio of 32-to-1, Duplin has seen big payoffs from eastern North Carolina’s hog revolution in the past decade. The county’s revenues from sales and property taxes have soared, and Duplin’s per capital income has risen from the lowest 25 percent statewide to about the middle.

Pork production also has spawned jobs in support businesses in Duplin and neighboring counties. People in the hog business say farm odor—”the smell of money”—is a small price to pay for a big benefit. “These hog farms are putting money in people’s pockets,” says Woody Brinston [the county’s director of industrial development]. “Duplin County is booming.”

But even here, some bitterly resent the way the industry has transformed the way the countryside looks and smells. Some say that their property has gone down in value. Others note the contrasts in the economic picture. In Duplin

County, just 70 miles east of the booming Research Triangle [an area located between Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill with a large number of advanced electronic and biotechnology firms] the population hasn’t grown in 10 years.

Farm jobs are dwindling despite the rise in hog production.

Daryl Walker, a newly elected Duplin County commissioner, says he hears these arguments all the time. “If this is prosperity,” he says, “many of my constituents would just as soon do without it. They are scared to death that there are just going to be more and more hogs, and more and more of the problems that come with those hogs.

10

Thompson−Gamble−Strickland:

Strategy: Winning in the

Marketplace

V. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

31. Smithfield Foods: When

Growing the Business

Damages the Environment

CASE 31 Smithfield Foods

A subsequent letter to the editor of the Raleigh News and Observer said:

Last Sunday, returning from a weekend at Wrightsville Beach, we stopped at an

Interstate 40 rest area near Clinton. When we stepped from our car the stench brought tears to our eyes. So add to the ever-mounting environment damage the poor image our state now leaves with tourists heading towards our beautiful coast. We’ll never know many big tourism bucks are now and soon will be going elsewhere.

11

Endnotes

1 Quoted in the five-part series by Joby Warrick and Pat Stith, “Boss Hog: North Carolina’s Pork Revolution—

Hog Waste Is Polluting the Ground Water,” Raleigh News and Observer , February 19, 1995. This series, based on a seven-month investigation and run in the News and Observer , February 19–26, 1995, was awarded the

Pulitzer Prize for Public Service Journalism in 1996.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Charlie LeDuff, “At a Slaughterhouse, Some Things Never Die,” New York Times , June 16, 2000, p. A1.

5 Raleigh News and Observer , February 19, 1995.

6 Joby Warrick and Pat Stith, “Boss Hog: North Carolina’s Pork Revolution—Money Talks,” Raleigh News and

Observer , February 24, 1995, p. A9.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Joby Warrick and Pat Stith, “Boss Hog: North Carolina’s Pork Revolution—Pork Barrels,” Raleigh News and

Observer , February 26, 1995.

11 Raleigh News and Observer , March 4, 1995, p. A10.

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2004

C581