Four Decades of the Advanced Placement Program

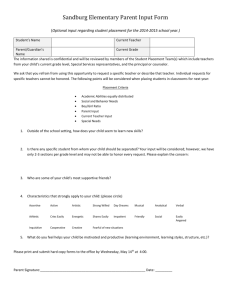

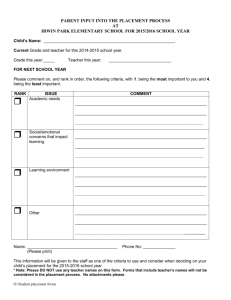

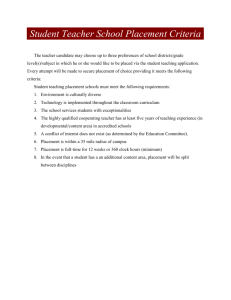

advertisement