- Royal Exchange Theatre

advertisement

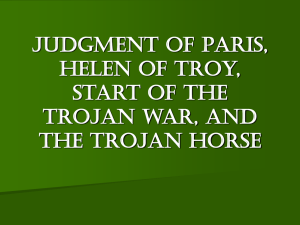

Thu 8 May – Sat 7 June 2014 Written by Simon Armitage Directed by Nick Bagnall Designed by Ashley Martin-Davis Lighting Chris Davey Sound Pete Rice Composer Alex Baranowski Fights Kevin McCurdy Assistant Director Liz Stevenson Performed by Gillian Bevan (Hera), David Birrell (Agamemnon), Richard Bremmer (Zeus), Clare Calbraith (Andromache & Thetis), Lily Cole (Helen Of Troy), Garry Cooper (Priam), Jake Fairbrother (Achilles), Simon Harrison (Hector), Brendan O’Hea (Patroclus & Sinon), Alfie Ryan (Astyanax), Tom Stuart (Paris), Colin Tierney (Odysseus) and Francesca Zoutewelle (Athene & Briseis) RESOURCE EXTRA This Resource Extra has been created with Key Stage 4 & 5 English, Drama, Media and History students in mind, although content can be adapted to suit other ages and subjects. INTRODUCTION In 700BCE, an epic poem called The Iliad, which had travelled around in the heads of entertainers who would recite the poem aloud, finally got written down. We attribute this version of the story to a man called Homer, although it may have been refined or added to by various individuals as it got passed down between entertainers, and recited in various locations from memory. The Iliad tells the story of the Trojan War – a ten year long conflict in which a Greek army sailed to Troy and camped outside the walls of Ilium, in order to recover what was stolen from them - Helen of Troy. Paris – a Trojan prince, stole Helen from her husband Menelaus, the head of the Greek army, ten years ago, triggering this lengthy combat. The Trojan War is thought to have happened over 500 years before Homer was born (in around 1200BCE). The Iliad also focuses in on a tiny slither of the Trojan War (about 50 days near the end of the ten year conflict), when internal divisions within the Greek and the Trojan armies are threatening to tear both sides apart. The stakes are high, the war has been drawn out for a long time, the Greeks have been away from their homes and families for almost a decade— the dramatic situation is extreme. There are also many gods in the dramatic world of The Iliad, and those gods are anthropomorphic – that is, they take on human shape. They are like a large unruly human family. It is a patriarchal family, with Zeus and Hera as the married, squabbling couple with 1 various sulky children. Their arguments mimic the antagonism between the Greeks and the Trojans, and they intervene in the conflict to make it longer. They also enjoy the same pleasures as humans; the only difference is that the gods can’t die. What does the presence of gods do to the story? Are they trivialized by their petty in-fighting, or even by their immortality? Does death and mortality, paradoxically, give meaning to human lives? EPIC POETRY Since the 17th Century, literature has been classified into categories such as the novel, the play, the poem, etc. Before this, these categories didn’t exist. Instead, literature fitted into different genres. These included Comedy, Tragedy, Romance, Pastoral, Satire and Epic. Epic was the most grand, with the most gravity. It was also very expansive, made up of long poetic lines, and also incredibly long: The Iliad is composed of over 15,000 lines, divided into 24 separate “books”. It would take three days to recite in its entirety. P. Toohey, Reading Epic: “An epic is a long narrative…concentrating on the fortunes of a great hero or civilization, and the interaction of this hero/civilization with the gods. [. . .] It generally involves glorification of the past.” Could this description of epic literature be applied to the way in which more recent events have been mythologized, such as D-Day, or the Blitz? Why do films like Elizabeth, or Troy (starring Brad Pitt), Lord of the Rings, or even TV shows like Game of Thrones continue to be popular? EPIC TODAY “The famous singer was singing to them, and they in silence Sat listening. He sang of the Achaians’ bitter homecoming From Troy, which Pallas Athene had inflicted upon them.” The Odyssey, l.325-7 This quotation, taken from another epic poem attributed to Homer that picks up the story of the homecoming of the Greek survivors after the Trojan War, describes the way in which these stories would originally have been communicated to an audience. The epic tradition was an oral tradition, and The Iliad was designed to be recited as song, memorized by rhapsodists (entertainers) to pass on. Although epic later became a very elitist and literary tradition, we have more recently recovered it as a populist tradition through vibrant film and theatre adaptations. The singer (the poem would be recited along to a lyre – a stringed musical instrument) would present his poem using set elements like rhyme and repetition, and recurring story patterns, making it easier to remember, whilst allowing him to improvise around a structure. This is comparable to modern day jazz or rap. WHY NOT? Explore the connection between oral epic storytelling and today’s theatre production. Nick Bagnall (the play’s director) describes how he wanted this production to be accompanied by original music, aiming to create “a constant heartbeat to the world, exploring rhythm, voice, song and strange instruments—aiming to create something exotic and other-worldly”. How was this achieved and what was the effect? When the director spoke to Simon Armitage (who wrote this adaptation) about the characterization of the gods, Simon quoted a lyric from a song by Bob Dylan: “Even the 2 president of the United States sometimes has to stand naked”. Nick says that, for him, this line resonated very forcefully. Why do you think that is? How is Zeus presented in this adaptation and in this production? Can you relate his characterisation to Bob Dylan’s lyric, and to the presentation of the gods in epic poetry? SIMON ARMITAGE’S ADAPTATION There are various source materials from which the adaptor has drawn in putting together this version of the last days of the Trojan War. The Iliad has already been mentioned. Another epic poem by Homer called The Odyssey, dealing with the aftermath of the war, fills in certain details including the episode surrounding the use of the Trojan Horse. Another epic poet called Virgil took up the story again over 600 years later in an epic poem about a Trojan survivor called Aeneas. In Book 2 of The Aeneid, Virgil flashes back to the last days of Troy. However, the story has proved popular and enduring in many other ways. An Elizabethan dramatist called Christopher Marlowe included a reference to Helen of Troy in his play Dr Faustus (1592). Helen has become a shorthand for the most beautiful woman in the world, and Marlowe referred to her as in his play as “the face that launched a thousand ships”, illustrating that she was a central cause of the Trojan War. Shakespeare took up the story himself in a play called Troilus & Cressida (1602). The film Troy (2004), starring Brad Pitt and Eric Bana, is only the most recent adaptation of a story that has held our interest and attention for over 3,000 years. WHY NOT? Discuss what it is about this story that makes it appeal to writers and adapters throughout history. Why is the Trojan War one of the foundational myths of Western culture? What are its themes and why do they continue to be of interest? Simon Armitage had to condense these massive books into only 2-3 hours of performance. As a result, the over 400,000 participants in the Trojan War have been reduced to a cast of 12. The many gods who make an appearance in Homer’s narrative are limited to Zeus, Hera and Athene in Armitage’s version. The character of Odysseus is an amalgamation of several high-ranking nobles in the Greek army. Similarly, the 15,000 lines of poetry in Homer’s version allow him to introduce many different plotlines and digressions, whereas this version has sought to condense the plot into a tight dramatic narrative. Can you spot any other ways in which Armitage has achieved this objective? However, despite the process of distillation that Armitage has undertaken, he has made two distinctive choices that set his adaptation apart from his source texts. Menelaus, the Greek leader who has been cuckolded by Paris (who stole Helen of Troy), is a central figure in Homer’s epic poem, but never appears in this version. Similarly, Helen is only a peripheral character in Homer’s story, and is rarely seen. In this production, she is much more central and vocal. WHY NOT? Explore the reasons why Armitage might have made these two choices. What is the effect of keeping Menelaus offstage? Similarly, what does it do to the story to make Helen of Troy so visible and to give her a strong voice in this production? 3 CASTING “I make sure I cast early and well” (Nick Bagnall, director of THE LAST DAYS OF TROY) Casting is one of the most important stages of any production. Nick has talked about the casting process for this production being especially creative and exciting. Indeed, one of the most striking features of this production is its casting. Helen of Troy is being played by Lily Cole. Nick Bagnall describes how Helen “is about a man’s perception of beauty and the idea that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. There is sadness and longing in Helen of Troy.” WHY NOT? Research the background of Lily Cole. What other work has she done and what is she known for? How might this information be interesting in relation to the role she plays in this production? What is the function of Helen of Troy in the story? Why do you think the director was excited to cast her? Would an audience have certain associations with Lily Cole that might inform their response to the character and the production? What is the importance of casting more generally? Can you find other examples in the production of the way that casting might contribute to the production in intriguing or creative ways? Why do you think the director chose that actor for that specific role? What do they bring to the role that another actor might not? Are there interesting similarities or differences between the actor and the role they have been asked to play? What are the potential effects of that casting choice on an audience? CONTEMPORARY RELEVANCE The Iliad is the first story about war, and 5,500 lines (approx. one third) of Homer’s epic poem are given over to battle scenes. This year is the centenary of the First World War (1914-18), another lengthy conflict in which many young men were sent far away from home, some of whom never returned. What kind of discussions emerge in such a year? How might you relate those discussions to the themes of THE LAST DAYS OF TROY? This production opens with the god Zeus looking back on the conflict from the present day (in Hisarlik, Turkey, thought to be the site of the ancient city of Troy) and describing the horrors of war. Why do people go to war? At whose request? These are still urgent issues in today’s society. Nick Bagnall suggests that: “As a society, we are in a place at the moment where the army are recruiting from young offender institutions, and men are going to war to fight and die for causes they don’t understand.” The war between Greece and Troy also pits West against East, perhaps resonating with other contemporary conflicts – the West’s War on Terror and Islamic extremism that escalated in the aftermath of the attack on the Twin Towers on September 11th 2001. 4 WHY NOT? Pick up a newspaper, or search for contemporary accounts of a conflict, speeches, images— what atmosphere is created? How do those accounts compare with Zeus’s account (see appendix 1) of the Trojan War in the opening scene of this play? How have more contemporary conflicts been justified? Is Helen, for instance, the original Weapon of Mass Destruction? (Iraq’s possession of WMDs was, of course, the pretext on which Blair and Bush invaded Iraq in 2003). Director Nick Bagnall was particularly struck by a speech given by Colonel Tim Collins as he prepared to take the 1st Batallion Royal Irish Regiment into Iraq in 2003. He says that “the use of Collin’s language hurt, intrigued, angered and amazed me”. You can watch actor Kenneth Branagh re-enacting Tim Collins’ speech here, for the BBC production 10 Days to War: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UpdeNcH1H8A What do you make of Collins’ speech? What is it about his language that might have “hurt, intrigued, angered and amazed” the director? How does Collins motivate his troops? How does his rhetoric relate to the glorification of war, or the depiction of the horrors of war? How does it discuss death and mortality in relation to war? How does it frame the enemy? How do you relate Collins’ speech to THE LAST DAYS OF TROY? PRODUCTION DESIGN “Glittering Troy” Andromache, with reference to the tapestry being woven by Helen of Troy, scene 3. “Have the whole camp tidied and swept, till there isn’t a flea still breathing. Once the vermin are cleared, sacrifice bulls and goats” Agamemnon, ordering Odysseus to clear up the Greek camp, scene 2. “Cinders where there were lavish throne rooms. Statues toppled.” Agamemnon’s vision for destroying Troy, scene 6. The designer Ashley Martin-Davis has used costume in this production to create distinct identities for the Greek and Trojan communities, as well as the world of the gods. As director Nick Bagnall puts it when describing his collaboration with the designer: “We both knew we couldn’t do this production with men in togas and masks. We wanted to find a balance between the contemporary, the classical and the magical and throw it all in there.” WHY NOT? Explore the ways in which costume works to evoke a Greek atmosphere or a Trojan atmosphere? What is the significance of colour, or the materials used by the designer to create these costumes? What do these choices symbolize? As Zeus says in scene 11, titled ‘No man’s land’: “…just when it looked as if Menelaus might rip Paris’ head from his neck or choke him to death, an unworldly mist closed in around them, ghostly, thicker than smoke, clammy to the skin.” Simon Armitage’s adaptation, like Homer’s Iliad, is full of references to fog and mist. How is that translated into the design of this production? Is mist used to conceal and reveal people and objects? What is the symbolism of this? 5 Staging a fight or a battle presents many challenges to designer and director alike. That’s even before we consider the major set pieces of the narrative that involve big design objects like the Trojan Horse, Helen’s tapestry, or Priam’s parapet. How has battle been staged in this production? Are fights staged realistically, like we have come to expect in the cinema, or are they more stylized? How effective are the theatrical strategies for staging and evoking war that are used in this production? Nick Bagnall describes how he and the designer favoured poetic rather than literal choices in the design process. At all times, they have aimed to create “an epic space with minimal props and furniture”. Usually the Royal Exchange module (our name for the glass theatre structure, suspended in the middle of the Great Hall) is used in-the-round, with audiences sitting on all sides of the playing space. However, for THE LAST DAYS OF TROY, the designer has moved slightly away from an in-the-round design. Why do you think this choice was made? What does the large gate-like structure allow the director and designer to do? The large design element that takes up one side of the traditionally in-the-round seating area also allows the director and his actors to make use of structural levels. How are these different levels used in performance? As well as the official cast of characters, this production also includes up to twenty supernumerary performers in each performance. Supernumerary performers are often drawn from local amateur groups, collages, or just the local community, and under professional direction they bring added life to a scene in non-speaking roles that give a sense of credibility to the world being staged. How and when are these supernumerary performers used? To what effect? THINGS TO CONSIDER At one point in Simon Armitage’s script, he calls for “several thousand Trojan soldiers to surge across no-man’s-land” – how might you realize this in performance? Look for this moment in the production – how do Nick Bagnall and his actors deal with this stage direction? How effective is their strategy? What props are used, how many actors, and what elements of set? How do they make use of the space? Another challenging moment involves the Trojan Horse, smuggled into the walled city as a gift, but secretly containing hundreds of Greek soldiers ready to burst out and inflict violence within the walled city. How have the director and the designer solved this design challenge? What is the symbolism of the choices they have made to depict this moment, and how does it relate to the major themes of the story? ACTING “It’s essential that I allow the actors to tell the story with clear intentions, and by excavating these beautiful texts and stripping away any fuss and allowing the words to breathe and connect and engage with the audience, that’s all we need.” (Director, Nick Bagnall) When working with his actors, Nick will constantly ask them to be clear on their intention. An intention is a word that describes the effect that a speaker aims to have on the person they are speaking to. If you were asking somebody out on a date, for example, you might attach various intentions to the words that you speak: for example, to persuade; to entertain; to 6 charm; to impress; to make laugh; to seduce. The intention should always describe the effect your words seek to have on the other person. WHY NOT? Look at scene 3 (appendix 2), the exchange between Helen and Andromache. This is an interesting scene because the women are, on the surface, talking about the tapestry depicting current events that Helen is weaving. However, the subtext of their discussion involves Andromache trying to find out where Helen’s allegiances lie (with the Greeks, her native community, or with Paris and the Trojans). As Andromache says, half way through the scene, “But where are you in all this? Where’s Helen?” The tapestry offers Andromache the perfect excuse to ask more penetrating questions. The director has said that he doesn’t want to know where Helen’s allegiances really lie – whether she is at heart a Trojan or a Greek. That is for the actress to decide. Go through the scene yourself and work out what each character’s intention might be, line by line. How might they communicate that intention in performance? When you watch the scene in performance, try and work out what the intentions of the performers are. What are they trying to do to the other person with their words? When you watch Helen, where do you think her allegiances lie? Does this change scene by scene, or even line by line? 7 Appendix 1: ZEUS’S SPEECH IN ACT 1, SCENE 1 Ten years into this most gruelling of military confrontations and we’re still no closer to any kind of resolution. A decade ago, leaders and warlords from almost every kingdom in Greece mobilized a task force of something like a hundred thousand men, sailed east, pitched camp on the shore and laid siege to the walled city of Troy on the far bank of the Scamander River. Motive: vengeance. Objective: return Helen to her rightful country and lawful husband. Progress thus far: nil. Current situation: stalemate, with neither Greeks nor Trojans prepared to surrender an inch of ground or contemplate defeat. On one side, under Agamemnon’s command, conditions in the Greek base are squalid and the morale of homesick and weary men impossible to judge. On the other side resources are running low and nerves are threadbare in King Priam’s besieged citadel. It’s hard to see this concluding without some allout catastrophic battle, an end-game or finale, like a great storm that clears the air, and when it comes may the gods have pity on those who hear its thunder. But until that time dark clouds mass overhead. The immovable object holds firm against the irresistible force, and this terrible war drags on. And on. 8 Appendix 2: AN EXTRACT FROM ACT 1, SCENE 3: HELEN AND ANDROMACHE A sunlit upper room within the walled city of Troy. HELEN is working at a long-by-narrow tapestry. Enter ANDROMACHE. ANDROMACHE This is where you’re hiding. Paris is looking for you. HELEN He knows where to find me. ANDROMACHE Yes, always in here in this room, always weaving. What is it anyway, some kind of map or story? HELEN It speaks for itself, doesn’t it? ANDROMACHE Yes it speaks, like the woman who weaves it, but what does it say? HELEN Greeks here. ANDROMACHE With their long hair and dark ships, camped on the beach. HELEN Trojans here. ANDROMACHE Glittering Troy. HELEN And war in between. ANDROMACHE Here’s a man skewering a man through the lungs with a spear, and the guts spilling out. And someone sliced in half by a chariot wheel. You have an eye for detail, no doubt about that. HELEN Ten years a student, and a grandstand view. ANDROMACHE (pointing at the tapestry) Is this me? It is me, isn’t it, in the blue dress. Holding Astyanax—I like the cute smile you’ve stitched on his little face. And Hector standing behind. Why is his sword drawn? HELEN Protection. Love? ANDROMACHE And none of your business, actually. But where are you in all this? Where’s Helen? 9 HELEN It’s unfinished. ANDROMACHE Of course, how could it be complete without the world’s most beautiful woman, the most beautiful woman since the beginning of time? HELEN So where would you position me? ANDROMACHE If we Trojans win you’ll be here, a princess of Troy, my sister in law, blowing kisses from the balcony onto the jubilant crowd below. If the Greeks triumph you’ll be over there, the rescued queen, carried home on a float, showered with jasmine and myrtle. Wearing my jewels I suppose. HELEN Was Paris really asking for me, or is this you, out hunting. ANDROMACHE Oh yes, I know exactly where you fit in: on the arm of whichever man gives the victory speech, and with a cemetery in the background, downwind. HELEN I was a wife in Greece, now I’m a wife in Troy. 10 Appendix 3: PRODUCTION PHOTOS 11 For rehearsal images please visit www.flickr.com//photos/rxtheatre/sets/72 157644299855125/show If you have any comments regarding our Education Resources, or if you would like to find out more about pre- and post-show workshops for schools and groups, please get in touch with our Schools’ Programme Leader Natalie Diddams on natalie.diddams@royalexchange.co.uk 12