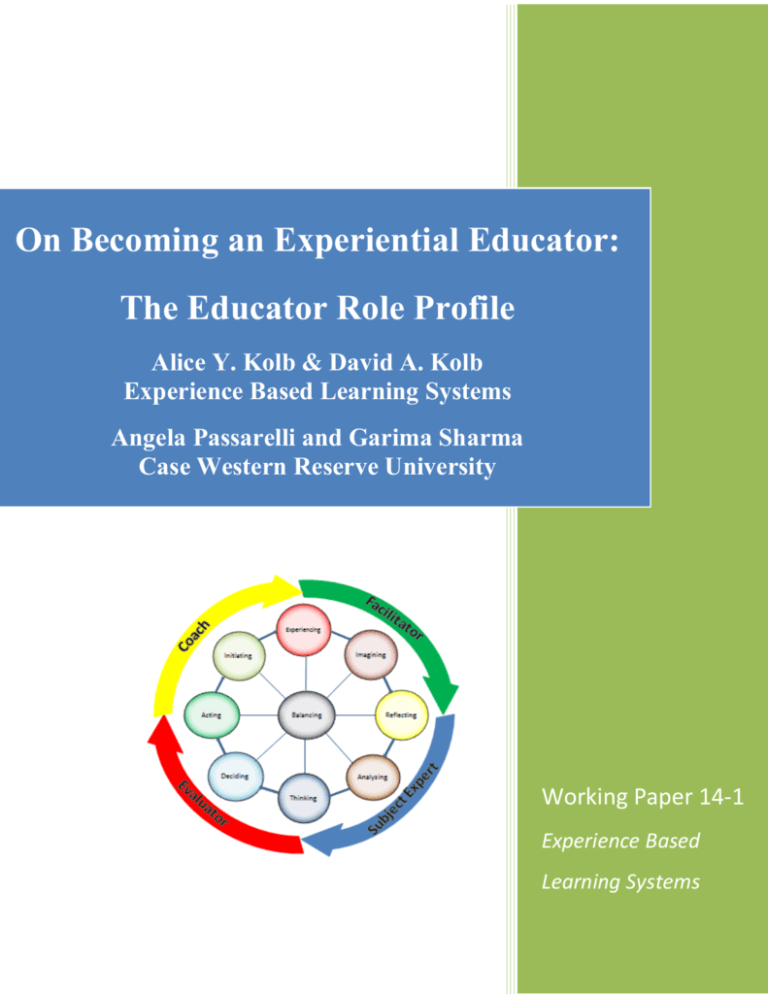

Now - Experience Based Learning Systems, Inc

advertisement