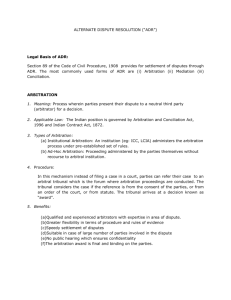

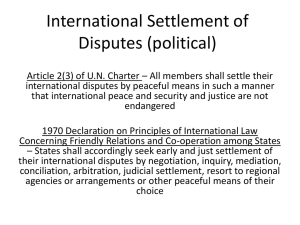

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in the Philippines

advertisement