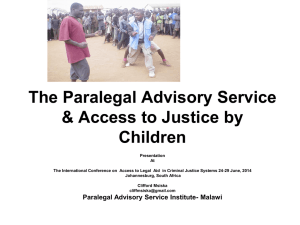

Community-Based Paralegalism in the Philippines

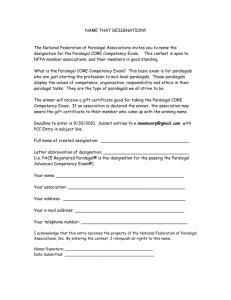

advertisement