New Directions in Management Development

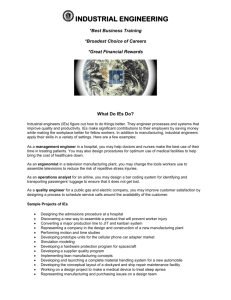

advertisement