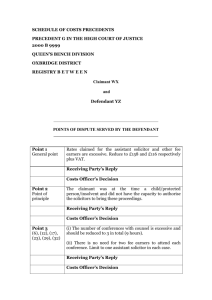

Report of the Legal Costs Working Group

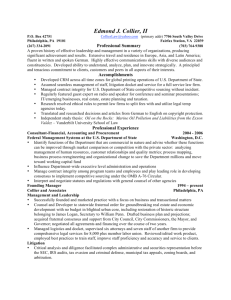

advertisement