STRUCTURE, POLITICS, AND ACTION

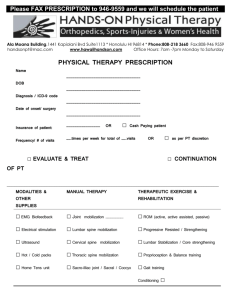

advertisement