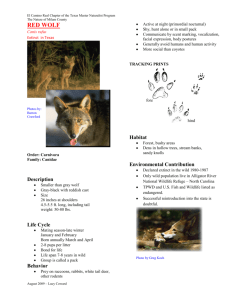

Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan

advertisement