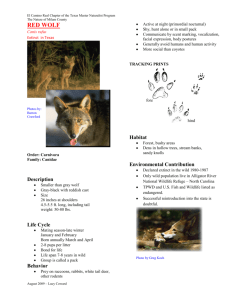

LARGE CANID - Association of Zoos and Aquariums

advertisement