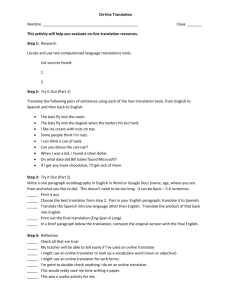

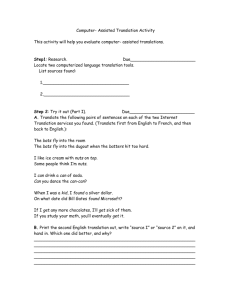

Spencer 1 Katrina Spencer Dr. Christine Jenkins

advertisement