Chapter One: Roman Cologne - University of Minnesota Twin Cities

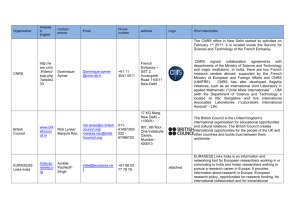

advertisement