ONLINE PLATFORMS FOR EXCHANGING AND SHARING GOODS

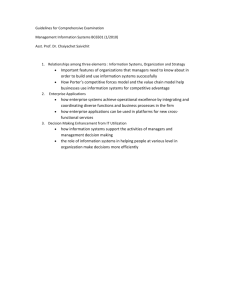

advertisement