A Guide to Careers in Administrative Law

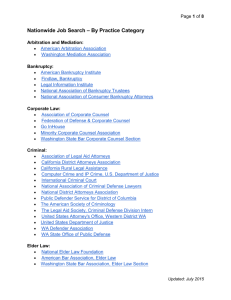

advertisement