OBAMA THE POPULIST? - Wake Forest University

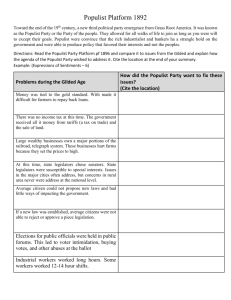

advertisement