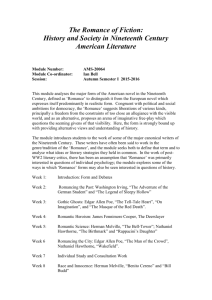

The American Romance - John-F.-Kennedy

advertisement