Business ethics and moral skepticism

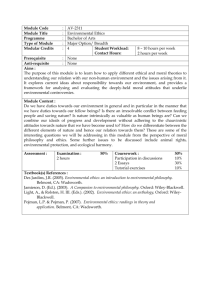

advertisement

Business ethics and moral skepticism ALAIN ANQUETIL1 Abstract The phrase ‘business ethics’ frequently evokes an incompatibility between business and ethics. Such an incompatibility reflects a negative skeptical attitude regarding the possibility of an ethics in business. This attitude raises in turn the following epistemological question: what was the influence of skepticism on normative theories that have been built in business ethics? In this paper, it is argued that skepticism have played a central and structuring role in normative theorization within this field. For this purpose, and using examples taken from the business ethics literature, we will try to show how business ethicists answer to this skepticism before exposing their theories and showing how they can address it. The argument will be presented in two steps. First, four species of skepticism will be considered. The first one is ideological: it is based on a radical criticism of the foundations of the market economy. The second kind of skepticism has an anti-theoretical dimension: it questions the practical relevance of ethical theory. The third, which pertains to meta-ethics, is concerned with the view that moral statements have no truth value and therefore lack any power of conviction. The fourth kind of skepticism refers to an egoistic account of moral human motivations, which reduces significantly the practical authority of morality. The second step of the argument will deal with the answers that have been proposed in the business ethics literature, especially within its normative branch, to these forms of skepticism. The metaethical and egoistic kinds will be more specifically considered. The former kind is often summarized by the phrase “separation thesis,” that is, the idea that business morality is less demanding than common morality. One answer to the separation thesis has been advanced by Freeman. It consists in changing the language with which business facts and practices are described. Another answer, proposed by Solomon, is that economic and non-economic activities are part of a single community governed by the same moral rules, and that each economic actor should consider himself as a member of this unique community. Two answers are also proposed with respect to the form of skepticism which lies in an egoistic account of moral human motivations. The first one has been emphasized in the “ethical philosophy for marketing” defended by Robin and Reidenbach. In their view, the proper function of business morality is to counterbalance the “limited sympathies” that characterize human relationships. The second answer, put forward by Sen, aims at showing that the belief that economic actors would be exclusively self-interested is not justified. This belief often relates to a famous passage of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, but Sen explains why it is misinterpreted. Our epistemological argument has two main consequences. First, it stresses the fact that skepticism about ethics in business should be taken seriously. In other words, its effects on practices and on theoretical constructions should be considered. Second, theories in business ethics should be detached from skepticism and based on criteria that define a good human life and good human relations in general. Key words : Business ethics, skepticism, normative theories, separation thesis, egoism. 1 - Professor of Business Ethics, ESSCA Ecole de Management, LUNAM, Associate Researcher, CERSES (UMR 8137) - alain.anquetil@essca RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 3 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL Résumé L’expression « éthique des affaires » évoque souvent une incompatibilité entre l’éthique et la vie économique marchande. Cette incompatibilité reflète une attitude sceptique sur la possibilité d’une éthique dans les affaires. Il en résulte une problématique épistémologique : celle de l’influence du scepticisme sur les théories qui ont été élaborées dans le champ de l’éthique des affaires. Dans cet article, nous défendons l’hypothèse selon laquelle une telle attitude sceptique a pu contribuer à structurer les approches normatives proposées dans l’éthique des affaires. À cette fin, nous montrerons à partir d’exemples issus de la littérature la manière dont les théoriciens répondent à ce scepticisme avant de proposer des positions normatives. Notre méthodologie se développera en deux temps. D’abord, nous distinguerons quatre formes de scepticisme sur l’éthique dans les affaires : la première, idéologique, est fondée sur une critique des fondements du système économique ; la seconde, anti-théorique, affirme que les théories morales ont peu d’utilité car elles sont déconnectées des pratiques des acteurs ; la troisième, méta-éthique, énonce que les principes moraux censés gouverner la vie des affaires sont dépourvus de valeur de vérité, ce qui implique qu’ils n’ont pas un pouvoir de conviction suffisant ; la quatrième repose sur une conception égoïste des motivations humaines qui compromet l’efficacité de l’éthique dans les affaires. Dans un second temps, nous traiterons des réponses apportées à ces formes de scepticisme. Nous présenterons ainsi plusieurs éléments permettant de vérifier l’influence du scepticisme sur les approches normatives de l’éthique des affaires. Nous traiterons en particulier des formes « métaéthique » et « liée à l’égoïsme de la nature humaine ». La forme méta-éthique peut être résumée par la thèse de la séparation, qui affirme que la morale de la vie économique est séparée de la morale ordinaire. Une réponse à la thèse de la séparation, due à Freeman, consiste à proposer un nouveau langage pour décrire la vie économique. Une autre réponse, due à Solomon, est de défendre l’idée que les activités économiques marchandes et les autres domaines de la vie humaine font partie intégrante d’un même ensemble régi par les mêmes règles morales, et que chaque acteur doit se penser lui-même comme membre d’une unique communauté morale. En ce qui concerne le scepticisme lié à l’égoïsme de la nature humaine, deux réponses sont présentées. La première se situe dans le champ du marketing. Proposée par Robin et Reichenbach, elle revient à concevoir la morale des affaires comme un instrument de compensation des « sympathies limitées » dont font preuve les êtres humains. La seconde réponse, formulée par Sen, revient à dénoncer les fondements de la croyance selon laquelle les acteurs économiques sont par nature égoïstes, une croyance qui s’enracine souvent dans une mauvaise interprétation d’un célèbre passage de La richesse des nations d’Adam Smith. Les apports de notre argument épistémologique sont de deux types. Le premier est qu’il convient de prendre au sérieux le scepticisme relatif à la place de l’éthique dans les affaires, c’est-à-dire de considérer ses effets non seulement sur les pratiques, mais aussi sur les constructions théoriques. Le second apport est que les théories de l’éthique des affaires devraient s’affranchir de toute attitude sceptique et partir de critères relatifs à ce que sont une bonne vie et de bonnes relations humaines. Mots clés : Éthique des affaires, scepticisme, théories normatives, thèse de la séparation, égoïsme. 4 RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL Resumen La expresión « ética de los negocios » evoca muchas veces una incompatibilidad entre la ética y la vida económica mercantil. Esta incompatibilidad refleja una actitud escéptica a propósito de la posibilidad de una ética en los negocios. De ello procede una problemática epistemológica : la de la influencia del escepticismo a propósito de las teorías que se han elaborado en el ámbito de la ética de los negocios. En este artículo, defendemos la hipótesis según la cual semejante actitud escéptica ha podido contribuir a estructurar los enfoques normativos propuestos en la ética de los negocios. Con este fin, demostraremos, a partir de ejemplos procedentes de la literatura, cómo reaccionan los teóricos frente a este escepticismo antes de proponer orientaciones normativas. Nuestra metodología se desarrollará en dos fases. En un principio, distinguiremos cuatro formas de escepticismo sobre la ética de los negocios : la primera, ideológica, que se fundó en una crítica de los fundamentos del sistema económica ; la segunda, antiteórica, afirma que las teorías morales tienen poca utilidad porque se han desconectado de las prácticas de los actores; la tercera, metaética, enuncia que los principios morales que supuestamente gobernan la vida de los negocios están desprovistos de valor de verdad, lo que implica que no tienen un poder de convicción suficiente ; la cuarta se funda en una concepción egoísta de las motivaciones humanas que comprometen la eficacia de la ética en los negocios. En un segundo tiempo, trataremos de las respuestas que se dan a estas formas de escepticismo. Presentaremos así varios elementos que permiten comprobar la influencia del escepticismo a propósito de los enfoques normativos de la ética de los negocios. Trataremos en particular de las formas « metaética » y « vinculada al egoísmo de la naturaleza humana ». La forma metaética puede resumirse por la tesis de la separación, que afirma que la moral de la vida económica está alejada de la moral ordinaria. Una respuesta a la tesis de la separación, que se debe a Freeman, consiste en proponer un nuevo lenguaje para describir la vida económica. Otra respuesta, que se debe a Solomon, es defender la idea según la que las actividades económicas mercantiles y los otros sectores de la vida humana forman parte íntegra de un mismo conjunto regido por las mismas reglas morales, y cada actor tiene que pensarse a sí mismo como miembro de una única comunidad moral. En lo que atañe al escepticismo relacionado con el egoísmo de la naturaleza humana, se ofrecen dos respuestas. La primera se sitúa en el sector del marketing. Propuesto por Robin y Reichenbach, consiste en considerar la moral de los negocios como un instrumento de compensación de las « simpatías limitadas » que manifiestan los seres humanos. La segunda respuesta, formulada por Sen, consiste en denunciar los fundamentos de la creencia según la que los actores económicos son por naturaleza egoístas, una creencia que se arraiga a menudo en una interpretación errada de un famoso extracto de La riqueza de las naciones de Adam Smith. Los aportes de nuestro argumento epistemológico son de dos tipos. El primero es que es preciso tomar en serio el escepticismo relativo al lugar de la ética en los negocios, o sea considerar sus efectos no solo sobre las prácticas, sino también sobre las construcciones teóricas. El segundo aporte es que las teorías de la ética de los negocios deberían liberarse de cualquier actitud escéptica y empezar desde criterios relativos a lo que son una buena vida y buenas relaciones humanas. Palabras clave : egoísmo. Ética de los negocios, escepticismo, teorías normativas, tesis de la separación, RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 5 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL Introduction Moral skepticism has an important place in the academic field of business ethics. It is not a radical skepticism such as the attitude which gave rise to skeptical doubt in ancient philosophy, but rather an uncertainty about the possibility of behaving morally and leading an ethical life in the context of business. The skeptical attitude has of course a positive dimension. It corresponds to the etymological meaning of the word “skeptical,” from the Greek skeptikos, which means “examining, observing, reflective” (Godin, 2004, p. 1177). It refers also to an essential aim of skepticism, that is, fighting dogmatic thought, especially religious dogmatism. But the skeptical attitude has also a negative dimension. It is particularly present in the normative edge of the business ethics literature, which aims at building theories that describe the organizational conditions allowing economic agents to act rightly and lead a good life. As it often appears, such theorists begin by mentioning some sort of skepticism about the possibility of establishing ethics in business – or at least their own interpretation of skepticism – before exposing their theories and showing how they can address it. Understanding the influence of the negative skeptical attitude on business ethics is a complex task that we will not undertake here. Rather, we will try to stress the way the skeptical attitude has been connected with some significant normative conceptions in business ethics. In particular, we will try to underpin the epistemological argument that the negative skeptical attitude regarding the possibility of an ethics in business may have structured, of course partially, the academic field of business ethics. This argument is rather hypothetical. There is no guarantee that it can be empirically verified. Naturally, other factors have shaped the field, such as the advent of a globalized economy, the diversity of social pressures exerted on firms, or the dramatic effects of financial scandals. But the negative skeptical attitude is presumably one of them. Moreover, it is an important component of the “separation thesis,” a famous claim of Edward Freeman (1994, 2000), one of the proponents of the stakeholder theory, a dominant paradigm in business ethics. The separation thesis asserts that ordinary morality and business morality are deeply separated. A negative skeptical attitude can also be found in Robert Solomon (1992), who defends a moral philosophy for business inspired from an Aristotelian ethics of virtue. It also appears through the huge efforts that have been devoted to correct the false interpretation of Adam Smith’s assertion that the individual pursuit of self-interest is the sole source of collective prosperity – the “invisible hand paradigm.” To begin with, we will propose some general considerations with regard to the roots of skepticism about ethics in business. Four forms of skepticism will be considered. The first is ideological; the second has an anti-theoretical dimension; the third, which pertains to meta-ethics, is concerned with the truth value of moral statements (for simplicity’s sake, it will be termed “meta-ethical”); the fourth rests on an egoistic account of moral human motivations. In the second part, we will present some of the most significant answers to the last two forms, referring to a number of works in business ethics which have contributed to the normative wing of business ethics literature. 6 RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL 1. Some species of skepticism about ethics in business One may wonder why the negative skeptical attitude on morality in business is of first importance within business ethics literature. Admittedly, the skeptical attitude is central to such scientific disciplines as physics or biology, but what is in question is the positive version of the skeptical attitude. It is part of the scientific approach. As Anne Fagot-Largeault (2002, p. 164) says with regard to the European scientific spirit, such an attitude relates to a “spirit of inquiry which is made up of an active curiosity, an ability to identify and formulate a research statement, a critical mind which questions the common view, and fidelity to the real world, giving at the same time an ethical dimension to the scientific method.” For any scientist, no theory is irrefutable, because doubt and criticism are intrinsic to the scientific method. However, the skeptical attitude we are concerned with here is not virtuous and positive doubt, rather a lack of confidence in the possibility of behaving morally and leading an ethical life in the context of business. We should specify that we do not distinguish here the concepts of doubt and skepticism, though they differ. In particular, the strong meaning of skepticism supposes a radical doubt, that is, the possibility of doubting everything. This form of skepticism was forcefully argued by Pyrrho, a Greek philosopher from Elis. He denied the possibility that any knowledge, or even any belief, may be justified. This view stands in contrast with scientific doubt, which demands that no judgment be made on a fact if no evidence is available. In this paper, we use the term “skepticism” in a sense akin to the word “doubt.” It refers to an a priori attitude of systematic incredulity and criticism over the authority of morality in business. We also suppose that this skepticism leads to a defensive attitude on the part of both business practitioners and business ethics theorists; in other words, they have to prove that business is indeed an ethical activity. Indeed, this negative side of skepticism is not only shared by many of those who are involved in the market economy, but also by many observers, including of course specialists in business ethics. In this respect, we should remark that the observers’ skepticism has often been regarded as one major cause of the difficulty in building a constructive dialogue between practitioners and theorists. Yet one of the requests made by practitioners to theorists was that the latter help them to set up moral criteria in order to make their practices legitimate – or, to put it another way, that theorists help them to prove that mistrust regarding the role of ethics in business is inappropriate. For theorists as well as practitioners, the task is difficult because skepticism about ethics in business takes different forms. Moreover, some of them particularly resist criticism. In what follows, we will be concerned with four sorts of skepticism – ideological, anti-theoretical, “metaethical,” and grounded on an egoistic account of moral human motivations. The first one is ideological. It rests on a harsh criticism of the foundations of the market economy and is related to a wider political, social and economic denunciation of the harmful effects of liberalism and capitalism. According to this view, the economic system based on free market hinders moral progress. The only way to resolve this state of affairs is to provoke a radical change of the economic system. However, ideological skepticism remains marginal within the field of business ethics, even though some arguments have been developed from it, for instance the one based on the Marxist concept of alienation (Corlett, 1988; RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 7 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL Sweet, 1993) or the place of democracy within the firm (McMahon, 2010). The second form of skepticism about the implementation of ethics in business may be called “anti-theoretical.” Bertrand Russell (1925), who did not believe that ethical knowledge can exist, proposed a striking example. In his view, desire is the source or every human behavior. Moral injunctions, if regarded as independent of desire, cannot produce any practical effect. We cannot appeal to and count on any ethical theory in order to make a right decision, regardless of our desire. “The superfluity of theoretical ethics is obvious in simple cases,” Russell writes (1925, p. 129). “Suppose, for instance, your child is ill. Love makes you wish to cure it, and science tells you how to do so. There is not an intermediate stage of ethical theory, where it is demonstrated that your child had better be cured. Your act springs directly from desire for an end, together with knowledge of means.” It is important to see that Russell does not exclude normative analysis, as he recommends that, in any choice, the expected consequences of the options be assessed. But he denies the usefulness of ethical knowledge if it is independent of desire. Such a rejection of ethical theory may foster a quite ordinary form of skepticism with regard to the practical authority of morality. It has also been observed within applied ethics, perhaps especially in business ethics. Arguments against the practical relevance of ethical theory have often focused on the too general character of normative conceptions stemming from moral philosophy, such as utilitarianism and deontologism (Cavanagh, Moberg and Velasquez, 1995). Even if moral advice given by these conceptions often reflect ordinary moral intuitions, such advice would in practice be ineffective in complex moral decision-making. Solomon (1992, p. 317) argues more generally that “a large part of the problem is that it is by no means clear what a theory in business ethics is supposed to look like or whether there is, as such, any such theoretical enterprise.” But he himself has laid the foundations of such a theory (see the second part). Besides, and quite naturally, a lot of normative work in business ethics has striven to build workable theories. For example, the ethical conceptualization proposed by Cavanagh, Moberg and Velasquez (1995) explicitly aims at helping practitioners to identify and make clear their moral reasoning and justify their decisions. Another typical case is the approach that Gene Laczniak and Patrick Murphy (1991) designed for marketers. It is based on a series of eight critical tests (“A sequence of questions to improve ethical reasoning”) with which any moral decision should comply. Rejection of ethical theory also results from the place of moral relativism in the normative landscape of business ethics. Relativism “denies that there is any universal moral code,” it is “the doctrine that there is no single true or most justified morality” (Wong, 1996, p. 1290). The sort of skepticism which is considered here – which means doubting the effective role allotted to ethics in business – is fueled by relativism. Indeed, some theoretical endeavors in business ethics have attempted to limit the extent of moral relativism. This is the case of the moral theory proposed by Robin and Reidenbach (1993), which rests upon a “bounded relativism,” and of the famous contractarian framework, named “Integrative Social Contracts Theory,” devised by Thomas Donaldson and Thomas Dunfee (1994), which leaves room for a certain degree of relativism. The third form of skepticism on ethics in business has been termed “metaethical,” with reference to the branch of moral philosophy which is concerned, in 8 RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL particular, with the meaning of moral terms, the truth value of moral statements and the motivational power of ethical judgments. We will briefly deal with the question of the truth value of moral statements. Examining whether moral statements may be true or false is intuitively important to explain skepticism about ethics in business. Scientific statements such as “Two plus two equals four” and “Water boils at one hundred degrees Celsius (under some initial conditions, i.e. at sea level)” are true. But is it the same for such statements as “Corruption is morally wrong” or “Profits should be shared out fairly among the stakeholders”? With regard to moral statements, emotivists (as well as expressivists and prescriptivists) contend that such statements simply express the speaker’s preferences. The agent who argues that “Corruption is morally wrong” is not referring to a moral truth. She is only asserting her own preference with respect to the problem of corruption. Moreover, by publicly expressing her judgment, she is seeking to convince her hearers that her judgment is right. Now, according to emotivism, moral statements articulated in a public context, e.g. a public debate, lack the power to convince. They would certainly be far more persuasive if they could be proven true as is the case for scientific statements. Doubt about the truth value of moral statements assuredly plays a role in the “moral muteness of managers,” a phrase devised by Frederick Bird and James Waters (1989). They stress how difficult it is for managers to express moral concerns in business contexts. Managers may even be led to remain silent on some moral questions they are confronted with. Such a moral muteness may be linked to the explicit or implicit belief that moral statements are less persuasive than scientific statements because they only express subjective preferences. Added to this is the belief that the public confrontation of moral statements expressing the participants’ subjective preferences results in sterile and insoluble debates. If moral muteness becomes the rule, it quite simply excludes moral considerations from debates regarding business and supports the belief that business morality is less demanding than common morality – which amounts to excluding ethics from business. Such devaluation refers to what has been called the “separation thesis,” which will be presented in the next part. The fourth form of skepticism about ethics in business is grounded on an egoistic account of human nature. If every reason for acting is self-interested – and, in addition, based on the quest for power and wealth – it is difficult, perhaps impossible, not to be pessimistic about the practicability of ethics in business. This skepticism stems for instance from Machiavelli’s Discourses, in which he insists on the importance of rulers’ willingness to dominate others and the desire for wealth that governs individual conduct. It also draws upon writers like Robert Michels (1911), who studied how the ruling class rise to power and secure their power. Such a framework is compatible with the model of homo economicus – the imaginary creature whose motives exclusively depend on his own interests – even though this model has been widely challenged within the social sciences, including economics. This form of skepticism is almost common in business ethics. It can be found in works regarding amorality and immorality in business – see, for example, Archie Carroll (1991). It also lies in the background of normative assumptions behind theoretical constructions such as the “ethical philosophy for marketing” defended by Donald Robin and Eric Reidenbach (1993). RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 9 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL 2. Responses of business ethics to skepticism about morality in business In this second part we expound some of the theoretical answers that have been proposed within the business ethics literature, especially within its normative side. We will only be concerned with the two last forms of skepticism. Indeed, we will not deal with the ideological form, as even basic answers to it and the objections it faces would entail an amount of political, economic and moral argumentation moving us beyond the field of business ethics. Objecting to the anti-theoretical form also goes beyond our present scope, as it is found in much recent debate within normative moral philosophy. Moreover, some considerations about the way some theoretical perspectives in business ethics incorporate moral relativism (in the form of a “bounded relativism”) have been alluded to in the previous part. Rather, we will be concerned most centrally here with the two other species of skepticism: first, “meta-ethical skepticism,” on which we will present the answers of Freeman (1994) and Wicks, Gilbert and Freeman (1994) to the “separation thesis,” and the refutation put forward by Solomon (1992); and secondly, the skepticism grounded on an egoistic account of human nature, referring to Robin and Reidenbach (1993), whose “ethical philosophy for marketing” relies upon egoism, and to Amartya Sen’s (1993) refutation of a famous and frequently misinterpreted passage in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Before proceeding, one thing should be said about the reason why these particular works have been selected here. It does not stem from their reputation within business ethics, even though this would possibly be a legitimate reason, but from the fact that their writers address the very issue of skepticism about ethics in business, before arguing for normative positions. A good way to deal with meta-ethical skepticism is to take the separation thesis as a starting point. This thesis holds that business morality is separated from common morality. Language lies at the root of this view. The idea appears clearly in Freeman (1994, p. 412): “The discourse of business and the discourse of ethics can be separated so that sentences like, ‘x is a business decision’ have no moral content, and ‘x is a moral decision’ have no business content”2. According to Freeman (1994), the separation thesis pervades not only the practices of business professionals, but also the views and theoretical constructions of some, if not a majority of, business ethics theorists. Thus, even without being aware of its influence, they presuppose a separation between two orders of language and morality. This is why Freeman proposes to change the language in order to rule out the detrimental effects of the separation thesis. The change in question should not exclusively apply to morality – another way to speak of such rules as “Reject corruption” or “Do not conclude agreements subject to antitrust laws.” It would also require a change in the way business facts and practices are described. The task consists in inventing a proper and refreshed vocabulary. Freeman and his colleagues Andrew Wicks and Daniel Gilbert (1994) thus undertake to renew some key aspects of the business vocabulary. In particular, they strive to partially replace five “masculinist metaphors” (without abolishing them), commonly used to describe business, with five “feminist metaphors.” 2 - For an account of the separation thesis, see (in French) Anquetil (2008, p. 19-28). This thesis has given rise to an abundant literature. For instance, Andrew Abela (2001) and Joakim Sandberg (2008) have identified respectively four degrees and nine sorts of “separation.” 10 RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL For instance, they suggest that the masculinist metaphor of hierarchy, which is commonly and often unconsciously applied to organizational structures, should be replaced by a metaphor, supposedly stemming from a feminist outlook, emphasizing a “radical decentralization and worker empowerment” (Wicks, Gilbert and Freeman, 1994, p. 491). Their perspective, also influenced by pragmatism and postmodernism, is typical of an attempt to answer the deeply rooted skepticism stemming from the separation thesis. In the first section of his paper, Robert Solomon (1992) tackles various theoretical frameworks that have been quite frequently invoked in order to set the foundations of business ethics. After highlighting their imperfections, Solomon contends that business ethics should be grounded on an Aristotelian moral philosophy. Such a framework attaches much importance to the development of virtues within the firm understood as a human community. But Solomon (1992) also offers a critique of skepticism about the place of morality in business. In his view, this skepticism is based on two prejudices. The first one stems from Aristotle’s distinction between household management (oikonomia) and commerce with a view to profit (chrematistike). The second type is oriented toward a purely mercantile aim, viz. maximizing profit (Aristotle, Politics, 1257b4). Consequently, it is not virtuous. As Solomon (1992, p. 321) reminds us, “Aristotle declared the latter activity wholly devoid of virtue and called those who engaged in such purely selfish practices ‘parasites’.” As for the second prejudice, which has a Christian origin, it is expressed in a “contempt for finance.” Such prejudices have helped to buttress the belief that business (understood here as “profit as an end in itself ”) is governed by very specific moral rules, that is, rules separate from those that govern the community. This is why Solomon (1992) puts forward a holistic theory which views the market economy and other domains of life as integral to a single community governed by the same rules. One need not consider that there are two different human communities, one devoted to economy and the other to non-economic activities. Indeed, there is only one community, and the theory of business ethics advocated by Solomon (1992) depends on the idea that every member of this single and widest possible community has to see himself as a member of this community. The way Solomon connects his theory with the skepticism grounded on the Aristotelian prejudice is eloquently expressed in the following passage: “Even defenders of business often end up presupposing Aristotelian prejudices in such Pyrrhonian arguments as ‘business is akin to poker and apart from the ethics of everyday life’ (Albert Carr) and ‘the [only] social responsibility of business is to increase its profits’ (Milton Friedman). But if it is just this schism between business and the rest of life that so infuriated Aristotle, for whom life was supposed to fit together in a coherent whole, it is the same holistic idea – that businesspeople and corporations are first of all part of a larger community, that drives business ethics today” (Solomon, 1992, p. 322). Let us now deal with some meaningful answers to the sort of skepticism about ethics in business which is based on an egoistic account of human nature. Importantly, in their attempt to define a “workable ethical philosophy for marketing,” Donald Robin and Eric Reidenbach (1993) rely on such an egoistic conception, which owes much of its inspiration to Thomas Hobbes. They refer in particular to Geoffrey Warnock (1971), who considers that morality should counterbalance the “limited sympathies” between people and RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 11 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL their “potentially most damaging effects” (Robin and Reidenbach, 1993, p. 100). According to Robin and Reidenbach, the language of “limited sympathies” fits well into marketing because marketers target particular segments of the market while ignoring those segments, i.e. people, who are outside the target. Moreover, they strive to satisfy exclusively the egoistic desires of those who are included in market targets. Robin and Reidenbach present a definition of the object of ethics that is worth quoting here because it refers to skepticism about the supposedly egoistic nature of man: “Ethics is an attempt by human beings to use their intelligence and capacity for reasoning to improve on the ‘law of the jungle’ conditions from which they evolved. Lower order animals lack this capacity and must face conditions in which power, in the form of force, speed, and instinct, as well as pure chance, dictates the length and quality of life. Power and chance are obviously part of the human condition as well, and with the addition of increased intelligence, the human capacity to use power is extended far beyond that found in any jungle. The moral dictates of societies and organizations represent an attempt to temper the use of power and perhaps at least reduce the grossest impacts of chance” (1993, p. 100). We may recall the reference Solomon (1992) makes to Milton Friedman (1970) in the passage quoted above.3 This famous economist is often associated with Adam Smith, although for certain reasons only, e.g. with regard to invisible hand arguments. And it is true that Smith has (unwittingly) fed a form of skepticism based on the “virtuous” effects resulting from supposedly self-interested economic agents. In a famous section of The Wealth of Nations, Smith asserted that “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love…” (Smith, 1776, p. 23-24). In Sen’s view (1993), this passage has been misinterpreted. That is, the view that collective prosperity only depends on individual self-interest has been wrongly ascribed to Smith. Sen reminds us that Smith speaks of self-interest in the narrow context of exchange, even a special category of exchange. In this much-quoted passage, Smith does not speak of the virtues of self-interest regarding production and distribution of commodities or distribution of wealth. As for production, for instance, the agents’ motivations are often “non-profit” or “non-self-seeking” motivations, as Sen says. The same is true for issues of distribution. In the end, “for Smith, commerce is a morally decent activity” and “people engaged in commerce have the capacity to be morally virtuous while engaged in economic activities” (Calkins and Werhane, 1998, p. 43). The important point here is that Sen relates his argument to skepticism about ethics in business, since that skepticism depends to a significant degree on the misinterpretation of Smith’s statement about the butcher, the brewer, and the baker. Sen’s paper typically begins with the idea that “that there is no need for such ethics” and concludes that “business ethics can be crucially important in economic organization in general and in exchange operations in particular” (Sen, 1993, p. 45 and p. 53). Even though he does not argue for a normative theory of business ethics as Wicks, Gilbert and Freeman (1994), Solomon (1992), and Robin and Reidenbach (1993) do, his argument, like theirs, is dependent on skepticism about the place of ethics in a market economy. 3 - Solomon omits the fact that for Friedman the context of business must be “without deception or fraud” (Anquetil, 2008, p.82). 12 RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL Conclusion What we have tried to show in this paper is that different forms of skepticism about ethics in business have played a central and structuring role in normative theorization within the field of business ethics. Of course, the skepticism in question is not a radical skepticism in a philosophical sense, rather an attitude of doubt and suspicion toward the possibility of acting well and leading a good life in the context of business. In the first part, we laid out some the forms that skepticism may take. Then we proposed four examples from the normative side of business ethics that illustrate the role played by the skeptical attitude – we should say rather different forms of such attitudes – in the construction and content of theories. At a minimum, as the previous examples show, skepticism, or one of its forms, has been used as a heuristic device. The epistemological hypothesis presented here has three limits which should be emphasized. The first is that the presumed influence of skepticism is restricted here to the normative branch of business ethics. Now, the discipline also includes a quite well developed empirical branch. But it was deemed more relevant to attend to the effects of the skeptical assumption specifically in the normative branch, as theoretical contributions are more elaborate than in the empirical – a point that will be not be expanded on here due to space limitations. The second limit comes from the fact that we have not offered a systematic analysis of the influence of skepticism on normative constructions in business ethics. However, we may observe that the four examples mentioned in the previous part correspond to significant and often-cited normative work in the discipline. In our opinion, they are sufficiently developed to support the epistemological hypothesis we argue for. The third limit relates to the absence of a well-established definition of the nature of the skepticism about ethics in business. We intentionally did not attempt to provide such a definition, although the same word, “skepticism,” has been used to denote the suspicious attitudes generated by four types of ordinary beliefs– ideological, anti-theoretical, “meta-ethical,” and related to an egoistic account of human motivations. Skepticism about the place of ethics in business should be taken very seriously. The robustness (and intuitive plausibility) of the four varieties presented argue in favor of it. An additional and crucial point is the fact that the role of ethics in business is best assessed in the light of the criteria that define a good human life and good human relations in general, e.g. with such fundamental capacities as sincerity, loyalty, and trust, which mean more than the simple absence of “deception or fraud,” as Friedman said. References Abela A. (2001), Adam Smith and the separation thesis, Business and Society Review, n°106, p. 187-199. Anquetil A. (2008), Qu’est-ce que l’éthique des affaires ?, Paris, Vrin. Anquetil A. (ed.) (2011), Textes clés de l’éthique des affaires, Paris, Vrin. Aristotle (1981), The Politics, tr. T. A . Sinclair, Harmondsworth, Penguin. Bird F.B. and Waters J.A. (1989), The moral muteness of managers, California Management Review, vol.1, n°32, p.73-88. Calkins M.J. and Werhane P.H. (1998), Adam Smith, Aristotle, and the virtues of commerce, The Journal of Value Inquiry, n° 32, p. 43-60. RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013 13 Business ethics and moral skepticism - Alain ANQUETIL Carr A.Z. (1968), Is bluffing ethical?, Harvard Business Review, vol.1, n° 46, p. 143-153. Carroll A.B. (1991), The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders, Business Horizons, n° 34, p. 39-48. Cavanagh G.F., Moberg D.J. and Velasquez M. (1995), Making business ethics practical, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.3, n° 5, p. 399-418. Corlett J.A. (1988), Alienation in capitalist society, Journal of Business Ethics, n° 7, p. 699-701. Donaldson T. and Dunfee T.W. (1994), Toward a unified conception of business ethics: integrative social contracts theory, Academy of Management Review, vol.2, n° 19, p. 252-284. Fagot-Largeault A. (2002), La construction intersubjective de l’objectivité scientifique, dans Philosophie des sciences, vol. 1, Paris, Folio Gallimard. Freeman R.E. (1994), The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.4, n° 4, p. 409-421. Freeman R.E. (2000), Business ethics at the millennium, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.1, n° 10, p.169-180. Friedman M. (1970), The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits, The New York Times Magazine. Laczniak G.R. and Murphy P.E. (1991), Fostering Ethical Marketing Decisions, Journal of Business Ethics, vol.4, n° 10, p. 259-271. McMahon C. (2010), The public authority of the managers of private corporations, in Brenkert G.G. and Beauchamp T.L. (dir.), The Oxford handbook of business ethics, Oxford University Press Michels R. (1911), Les partis politiques, Paris, Flammarion. Robin D.P. and Reidenbach R.E. (1993), Searching for a place to stand: Toward a workable ethical philosophy for marketing, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, vol.1, n° 12, p. 97-105. Russell B. (1925), What I believe, in Pigden C. R., Russell on ethics: Selections from the writings of Bertrand Russell, London, Routledge, p. 125-130. Sandberg J. (2008), Understanding the separation thesis, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.2, n° 18, p. 213-232. Sen A. (1993), Does business ethics make economic sense?, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.1, n° 3, p. 45-54. Smith A. (1776), An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations, New York, Bantam Classic Edition. Solomon R.C. (1992), Corporate roles, personal virtues: An Aristotelian approach to business ethics, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.3, n° 2, p. 317-339. Sweet R.T. (1993), Alienation and moral imperatives: A reply to Kanungo, Journal of Business Ethics, n° 12, p.579-582. Warnock G.J. (1971), The object of morality, London, Methuen & Co. Wicks A.C., Gilbert D.R. and Freeman R.E. (1994), A feminist reinterpretation of the stakeholder concept, Business Ethics Quarterly, vol.4, n° 4, p. 475-497. Wong D.B. (1996), Relativisme moral, in Canto-Sperber, M. (ed.), Dictionnaire d’éthique et de philosophie morale, P.U.F., p. 1290-1296 Wong D.B. (1998), Moral Relativism, in E. Craig, The Routledge encyclopedia of philosophy, London, Routledge, p. 539-542 14 RIMHE, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management & Humanisme RI/vol.1 - n°9 novembre/décembre 2013