LEGACIES OF SLAVERY?: RACE AND HISTORICAL CAUSATION

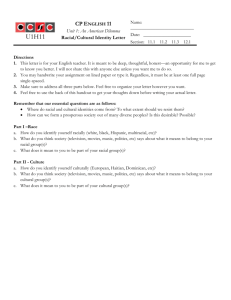

advertisement