Families and Social Capital: Exploring the Issues

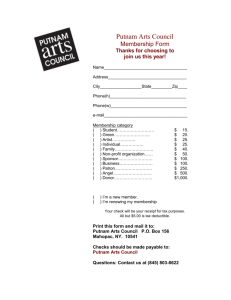

advertisement