Loanwords in Ket Edward J. Vajda

advertisement

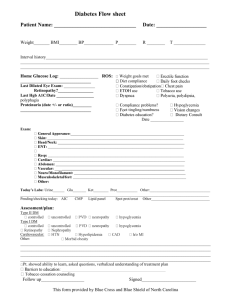

1 Loanwords in Ket Edward J. Vajda 1. The language and its speakers Ket is the sole surviving member of the formerly widespread Yeniseian (Yeniseian) family. Substrate river names and 17th century Tsarist fur tax records attest to the existence of other, now extinct Yeniseian-speaking groups throughout much of the taiga forests of central and western Siberia. Several of these languages were recorded in varying degrees of lexical and grammatical detail before they vanished. Figure 1, adapted from Vajda (2009+) shows the known members of the Yeniseian family in their likely subgrouping. Figure 1: Documented members of the Yeniseian language family 2 The Ket-Yugh subgroup (Northern Yeniseian) is obvious from ample lexical and grammatical homologies, as is the close connection between Kott and Assan. The position of Pumpokol is more difficult to assess. This language probably forms an early branch with Arin, as presented above; however, it may be that Arin and Pumpokol form separate primary nodes, a possibility that cannot be excluded given the scanty documentation of both languages. Because some Yugh material was misidentified as Pumpokol in the early attestations, identifying genuine Pumpokol forms can sometimes be difficult. The fullest and most accessible account of data known from the extinct members of Yeniseian can be found in Werner (2005). Today the Ket as an ethnic group number around 1200, but fewer than 200 can be regarded as fluent speakers. Exhaustive sociolinguistic surveys conducted by the ethnographer V. P. Krivonogov during the past two decades (Krivonogov 1998, 2003) attest to the rapid and apparently irrevocable language shift to Russian among the ethnic Ket, as well as to a rise in inter-ethnic marriages and the beginnings of a sort of Ket diaspora, where over 200 ethnic Ket have now left their native Turukhansk District to reside in other parts of the Russian Federations. Most fluent speakers of Ket are older than 50. As shown in Map 1, the location of villages where concentrations of Ket speakers reside today is generally farther north than the forests the Ket and other Yeniseian tribes inhabited during the 1600s, when Russians first made contact with them. 3 Map 1: Ket in its geographical context 4 Map 2: Location of contemporary speakers of Ket (shown in black) and of Yeniseian groups in 1600 as well as Yeniseian substrate river names (marked by labels such as -ses) 5 The labels -ses, -šet, and so forth in Figure 2 provide a rough approximation1 of areas located outside of the documented area inhabited by Yeniseian speakers that nevertheless contain river names based on cognates of the Ket word for river, ses, or water ul. These vast areas presumably represent places of former habitation of linguistic relatives of the Ket prior to the Russians’ arrival in Siberia after 1582. In many cases, the substrate river names appear to be closely related to one of the known Yeniseian languages: Ket (-ses, -sis), Yugh (-čes), Kott (-šet), Assan (-čet), Arin (-sat), Pumpokol (-dat, -tat). The widespread hydronymic formants -tys or –tyš, represented in the river name Irtysh and in the names of many smaller rivers in Western Siberia, may attest to a distinct branch of Yeniseian that otherwise disappeared without a trace. Because the hydronyms north of Mongolia and west of Lake Baikal are dialectally the most diverse, this general area likely represents the geographic origin of the Yeniseian-speaking tribes. The ethnonym Ket was adopted only in the 1930s, based on the word kɛ’t ‘person, human being’. Prior to this time, the Russians called the Ket “Yenisei Ostyak”, hardly distinguishing them from their linguistically unrelated neighbors to the west, the Selkup (formerly the “Ostyak-Samoyed”) and the Ugric-speaking Khanty (formerly known simply as “Ostyak”). In tsarist times, the Russians generally referred to all of the West Siberian forest people as “Ostyaks” of some sort, a term whose origin remains unclear; cf. Georg (2007: 11-15) for the most authoritative discussion of Yeniseian ethnonyms. Most Ket people today live in small villages on the middle reaches of the Yenisei River or its tributaries. The 1 Ket-related hydronyms of Siberia include additional minor variations (sis ~ ses ~ sas, set ~ sat, det ~ dat, etc.) not shown in Map 2 that are difficult to connect with specific Yeniseian languages or dialects since they appear to reflect nothing more than pronunciation adjustments on the part of the peoples who took over the given territory from Yeniseian speakers. South Siberian Turkic speakers, for example, probably harmonized vowel quality (e ~ a) to match the articulation of the preceding vowel in many cases. Also not shown are areas with river names ending in -tym, -tom, -sym, etc., which are of unknown origin but tend to be prevalent in areas known to be inhabited by Yeniseian tribes in the 1600s. Also not shown are toponyms in –tes, also conceivably Yeniseian, though no documented Yeniseian language shows this pronounciation of the word for river. Cf. Werner (2006: 148-156) for more detail on the distribution of early Yeniseian peoples and their cultures. 6 largest concentration – about 250 – is to be found in Kellog Village on the Yelogui River, though only a minority of these are fluent speakers. This village, like most locations inhabited by the Ket, is accessible to the outside world only by boat (in summer) or helicopter (year round). The Ket, as well as their documented linguistic relatives, were the last huntergatherers of North Asia outside the Pacific Rim. Having no domesticated animals besides the dog, the Yeniseian tribes had been pushed northward out of south Siberia by pastoral peoples such as the Yenisei Kirghiz. Even before the coming of the Russians the Ket had experienced centuries of encroachment from the reindeer-breeding Enets to the north and the Evenki to the east, as attested in Ket folklore. The Southern Ket, however, had formed a sort of social alliance with the Selkup-speaking reindeer-breeders to the west. All three dialects of Ket are rapidly disappearing today. Northern Ket was reported to have only a single speaker in 2006, though a second fluent speaker has since been identified. Attempts to write Ket using a Latin script based on Central Ket in the 1930s or a Cyrillic script oriented toward the Southern Ket dialect in the 1990s did little to reverse this trend, though basic lessons in Ket language continue to be given in the first few grades of primary school in Kellog and a few other villages even today. While most ethnic Ket spoke their language fluently and used Russian, at most, as a second language even as late as the 1920s, the events of the Soviet period irrevocably placed Ket on the path toward oblivion. During the 1930s the Ket were collectivized and forced to live alongside Russians and other Native Siberian minorities in the riverside villages where they currently reside, leading to a general adoption of Russian for interethnic communication. During the 1960s the Ket were forced to give up their children to boarding-school education where a Russian-only rule was vigorously enforced. This led to general language shift by the younger generations. By the time a new policy of ethnic education was adopted in the 1980s, leading to the creation of elementary language textbooks in the 1990s, most Ket children entered primary school speaking little or no Ket. As a rule, neither their parents nor even their schoolteachers were sufficiently fluent in Ket to pass it on as a native tongue. A few hours a week of elementary-school lessons of Ket as a second language could not reverse the overwhelming trend toward language replacement by Russian. 7 Today, it is generally only older adults, especially those born before the early 1960s, who retain strong fluency in their ancestral tongue. Even among this group there are no monolingual Ket speakers. For a concise overview of the history of Ket people and of the scholars who have studied them, see Vajda (2001). 2. Sources of data The first substantial publication of Yeniseian vocabulary came in 1858, with the posthumous appearance of Finnish linguist Mathias Castrén’s “Yenisei-Ostyak” grammar (Castrén 1858), which contained lists of words with their German translations. The “Ostyak” materials in this work primarily represent Yugh rather than Ket. This first Yeniseian grammar also contains the only extensive collection of Kott vocabulary and grammatical forms, as Castrén was the last scholar to work with native speakers of Kott. Earlier recordings of Yeniseian vocabulary – brief word lists of Arin, Pumpokol, Assan, Kott, Yugh and Ket taken down by explorers during 18th century – long remained accessible only through visits to the archives in Moscow, Leningrad or other places in the Soviet Union where they were housed (Vajda 2001: 341-351). Tomsk linguist Andreas Dulson gathered the data from these disparate sources and published them together for the first time, though in a regional periodical difficult to obtain outside of Russia (Dul’zon 1961). Fortunately, Heinrich Werner, a linguist from Tomsk who is now based in Bonn, Germany, has recently published a full compilation of all 18th century Yeniseian language documentation (Werner 2005). Werner’s monograph includes not only the materials published earlier by Dul’zon (1961), but also two vocabulary lists (one Arin, the other Pumpokol) newly discovered in the 1980s by Moscow linguist Eugen Helimski (Xelimskij 1986). Werner has also republished Castren’s 19th century Kott vocabulary, together with Kott words recorded in the 18th century, in a Kott-Russian glossary appended to his Kott grammar (Verner 1990: 284-394). Unfortunately, this work remains largely inaccessible, as it was printed in only 250 copies by a regional university (Rostov University). No comprehensive dictionary of either Yugh or Kott has yet been published. 8 Fortunately, all of the extant words from the extinct Yeniseian languages, including Castrén’s Kott dictionary materials have recently been published together with all of the Ket and Yugh vocabulary gathered during the 20th century. This magnum opus is Heinrich Werner’s three-volume Comparative Dictionary of the Yeniseian Languages, a work written in German with English and Russian glossaries at the end of the third volume (Werner 2003). At present, this dictionary can be regarded as the authoritative publication of all recorded Yeniseian vocabulary. Not only did Werner gather together all material on the extinct Yeniseian languages, he also greatly expanded the rather scant earlier publications of Ket vocabulary. At the close of the 20th century substantial compilations of Ket words were limited to three publications2. The first was a glossary of Central Ket published in German in a book about Ket ethnography (Donner 1955: 15-111). The second was a short dictionary and morpheme list of Southern Ket that appeared in a volume largely devoted to Ket texts and folklore (Krejnovič 1969: 22-90). The third was a Ket-Russian/Russian-Ket elementaryschool pedagogical dictionary with 4,000 Ket lexemes, based on Southern Ket (Verner 1993). Amazingly, no comprehensive dictionary of Ket appeared during the 20th century. The present study employs Werner (2003) as its basic source, supplementing it with new fieldwork among the remaining native speakers of Ket. In some cases, new words were discovered, in many other cases, it was confirmed that Ket lacks any word for a given item. This was particularly common for words denoting features of the natural world not present in central Siberia (‘palm tree’, ‘mainland’, ‘elephant’, and the like), as well as many items of modern culture and society with which Ket speakers had never come into contact (‘judge’, ‘oath’, ‘to convict’, etc.). Judgments about recent Russian loanwords into Ket listed in Werner (2003) were also elicited from these native speakers, and in a number of cases brought to light interesting facts about the sociolinguistic status of these items. These new findings will eventually contribute to the publication of two 2 Vajda (2001: 374) provides an exhaustive list of publication of Ket and Yugh vocabulary since the second half of the 19th century. These include several shorter lists, as well as a few pamphlets written to introduce Ket vocabulary in elementary school classes. 9 major new works on Yeniseian lexicon, both of which are currently in preparation under the sponsorship of the Linguistics Department of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig. The first is a comprehensive Ket-RussianEnglish-German dictionary of words gathered from all three Ket dialects reelicited in idiomatic context from the remaining native speakers (Kotorova ed. 2009+). The second is an etymological dictionary of Yeniseian aimed at explaining, whenever possible, the origins of all known Yeniseian vocabulary, including loanwords (Vajda & Werner 2009+). The present study has both informed and been informed by both of these projects. 3. Contact situations 3.1. Introduction As isolated bands of hunter-gatherer-fishers, the Ket evolved a vocabulary uniquely suited to their taiga and riverine environment. Up until the 20th century the Ket had little intensive contact with other linguistic groups, since they lived as small mobile bands in a vast northern forest. Most Ket words show no sign of borrowing and quite a number of them are semantically rather unique. There are nouns conveying special attributes of northern ecology: atɛ́tliŋ ōks 3 ‘a lone tree of one species in a pure stand of another species’, hʌlis ‘small raised mound in the tundra’, taʁo ‘swampy, treeless area in the taiga’, sɔlgup ‘point of land jutting out into a small river’, etc. Many words express details of forest life: ɯráq ‘spring camp’, itáŋ ‘distance traveled between two encampments’ (< ī ‘day’ + tàŋ ‘drag’), imtɛt ‘to harvest pine nuts’, tɯ̄t ‘swarms of bloodsucking insects (a major 3 The phonemic prosody in the Ket examples is transcribed using: a macron denotes high-even tone (ōks ‘tree’); an apostrophe denotes abrupt tone ending in glottal constriction (bɔ’k ‘fire’); a grave accent denotes falling tone (ùs ‘birch tree’); an acute accent denotes rising pitch on a second syllable (hɔráp ‘fish tail’); the lack of any tone mark on disyllabic or polysyllabic words indicates an initial syllable pitch peak (sɛniŋ ‘shaman’); finally, a double vowel denotes risingfalling tone on a geminate vowel (huut ‘animal tail’). The forms given are from the Southern Ket dialect unless otherwise noted. 10 feature of forest life in the brief summer)’, lilgej ‘the crunch of snow under moving sled runners’, qɯ’j ‘large piece of birchbark used to cover the summer tent’, etc. Characteristic words and phrases express key aspects of Ket spiritual culture: sɛniŋ ‘shaman’, hās ‘shaman’s drum’, allɛ́l ‘female guardian spirit image’, ulvéj ‘the primary soul from among the seven spirits associated with each person’. Fire was conceived as a feminine-class animate being: bɔ’k dγ̄p ‘fire burns’ (literally, ‘fire, she-eats’). The Ket used specialized, taboo-related vocabulary during their Bear Ceremony, an ancient tradition featuring the ritualized slaughter and consumption of a bear thought to be the reincarnation of a human relative; for example, huktɛŋ are ‘bear eyes’, while dɛstáŋ are eyes of other animals or people. A rich inventory of spatial adverbs expresses specific types of orientation with regard to rivers or lakes and forested land: igda ‘from the forest to the riverbank’, ʌtá ‘from water to shore’, aγá ‘from shore to forest’, ɛtá ‘movement on foot upriver along the ice’, etc. These adverbs can be incorporated into motion verbs. Some adjectives build classificatory distinctions involving animacy: sukŋ ‘thick (said of a tree)’, bōl ‘fat (person or animal)’, and bʌsl ‘fat, thick (object)’; ka’t ‘old, elderly (animals, people)’, qà or qa’ ‘old, big, grown up (said of children, young adults)’, and sīn ‘old (object or person; also said of large trees)’; kitéj ‘young (animals, people)’ and ki’ ‘new (object or plant)’. Some verbs have suppletive stems for animate- and inanimate-class subjects: dīn ‘he (person or animal) stands’ [du-k-ain 3MASC.SBJ-erect-PRES-stand], duγata ‘it (a masculine-class tree) stands’ [du-h-a-ta 3MASC.SBJ-area-PRES-extend], ujbɔʁut ‘it (a movable, inanimate-class object) stands’ [uj-b-a-qut at.rest-3INAN.SBJ-STATE-occupy.position]. Certain nouns describing natural phenomena are more elaborately classificatory than is typical of most Eurasian languages: bɛ’s ‘falling snow’, tīk ‘layer of fallen snow on the ground’, tɔqpul ‘layer of fallen snow on branches’; also, huut ‘animal tail’, hi’s ‘bird tail’, hɔráp ‘fish tail’. But certain kinship terms are surprisingly generic with regard to gender (bisɛ́p ‘brother, sister’, qīp ‘uncle, aunt’, qàl ‘grandchild, niece, nephew’), especially given the fact that Ket marriages were traditionally patrilocal and arranged on the basis of two exogamous phratries, called hɔγɔ́tpul (< hō ‘same’ + a’t ‘bone’ + hɯl ‘accumulation’). As far as can be ascertained, none of this specialized vocabulary is borrowed, though some of it could involve areal 11 metaphoric diffusion. For example, Mongolian groups also refer to kinship lineages using the word jas ‘bone’. Yeniseian vocabulary bears no clear genealogical affinity with other North Asian families. Contact with other peoples of Eurasian, however, either directly or through the mediation of neighboring tribes, has produced several layers of loanwords. By far the largest layer results from recent Russian contact. A much smaller set of loanwords derives from contact with the Samoyedic-speaking Selkup reindeer breeders, who were the western neighbors of the Ket, or from diffusion north from the Turco-Mongol world of the steppes much farther south. The few attested loanwords that originated from the steppes, e.g., talɯ́n ‘flour’ (cf. Halh Mongolian talxan), may have diffused into Ket via other languages of the taiga. It is possible that some words inherited from Common Yeniseian by Ket were borrowed from Turkic or Uralic at some very great time depth, but these are difficult to trace, and the direction of borrowing, if it occurred could have been from rather than into Yeniseian. Yeniseian words for 'birchbark', 'birch tree', 'reindeer', and 'falling snow' bear some resemblance to words in Uralic, while Yeniseian 'stone' resembles Turkic words for stone. 3.2. Contact with Russian Cossacks and other Russian-speaking adventurers began to infiltrate the middle reaches of the Yenisei watershed less than two decades after Yermak’s successful invasion across the Urals in 1582. The Ket and other Yeniseian-speaking peoples were soon incorporated into the fur-tax (yasak) system. Yasak entailed regular payment of sable and other pelts by the natives to a local representative of the Tsarist government, the voyevoda, who, as a rule, established a base camp in the form of a fort (ostrog) on some convenient riverway. Since the Ket were nomadic hunters, contact with Russians in this early period was limited to a few brief encounters every year, when yasak was delivered. In general, Ket groups tried to avoid the Russians for fear their kinsman would be kidnapped as a means of coercing regular yasak payments. The southern Yeniseian peoples were more 12 immediately affected by the Russian presence, since they found themselves torn between fur-tax obligations to the Russian newcomers as well as to the TurcoMongol polities of the forest-steppe fringe. In the taxation tug of war that developed, such peoples as the Arin and Pumpokol were devastated by reprisals taken against them by the Tatars for submitting to the Russian fur tax system. By 1735 the Arin as a distinct ethnic community had all but disintegrated. By 1800 the Assan and Pumpokol likewise melded with the local Russian or Turkic populations and their languages disappeared. The Kott lasted until at least the 1840s, when Mathias Castrén worked with the last five known native speakers. Social, geographic and linguistic data on the extinct Yeniseian peoples can be found in Dolgix (1960) and Werner (2005). Another factor that decimated all of the tribes of the Yenisei watershed to some significant degree was the introduction of European diseases (Alekseenko 1967: 26). Recurrent smallpox epidemics during the course of the 17th century (notably in 1627-28 and again during the period 1654-1682) all but wiped out the fisherfolk along the middle Yenisei, with the riverine Yugh especially hard hit. Although Yugh continued to be spoken by a few elderly people up to the early 1970s (Heinrich Werner, p.c.), already by the mid-19th century the tribe had decreased to several dozen individuals from an original population of probably ten times that number. Some of the Ket hunting groups, though affected by the same epidemics, fared somewhat better, as their mobile upland lifestyle took them away from close contact with the Russians and others living in the riverside zones hardest hit. The Ket were likewise fortunate in living far enough northward on the Yenisei so as to be out of range of reprisals by steppe peoples bent on keeping their subjects from submitting to the Russians. In fact, after the coming of the Russians, the Ket gradually relocated considerably farther upstream along the Yenisei. For most Ket groups, contact with the Russians continued to be limited to times when separate family hunting parties emerged from the forest onto the riverbank during the spring to fish and pay their fur tax. The sporadic nature of Ket contact with the Russians remained little changed until the 1930s, and relatively few words from Russian were taken into the language in this initial period. Early loanwords include trade items such as teslá ‘adze’ (< Russian teslo ‘adze’), kurúk ‘hook’ (< Russian krʲuk ‘hook’), and postóp 13 ‘glass bottle’ (< Russian stopka ‘shot glass’). There are also a few terms relating to Christianity, e.g., ho’p ‘priest’ (< Russian pop ‘parish priest’), though the Ket did not adopt the new religion but instead retained their traditional spiritual culture into the 20th century. Direct linguistic borrowing, however, was the exception rather than the rule, even for new realia. Rather, the Ket showed a more marked tendency to coin native terms for new objects, concepts, or social categories. A typical example of these neologisms is bogdóm ‘gun’ (< Ket bo’k ‘fire’ + qām ‘arrow’). Ket interaction with Russians underwent a drastic revolution as a result of Stalin’s collectivization campaign of the 1930s, which forced the Ket and other Native Siberians to settle in Russian-style villages where they came increasingly under pressure to deal with spoken Russian on a regular basis. During the 1960s the Soviet government intensified its policy of forcing Ket families to give up their children to Russian-language boarding schools. This seems to have triggered the crucial breaking point in transmission of the language, as Ket children born after the 1960s rarely learned fluent Ket. Older native speakers, however, continued to use Ket with relatively little influence from Russian, preferring instead to coin neologisms based on native morphological material, such as ēγ suul ‘iron sled’ for ‘automobile, truck’. Nevertheless, the majority of Russian loans seem to date after the period of collectivization. 3.3. Contact with other Siberian peoples The Yeniseian languages spoken to the south of Yugh and Ket, all of which became extinct before massive Russian influence could affect them, show loans from South Siberian Turkic, especially in the realms of stockbreeding, farming, or metallurgy: Kott bal ‘cattle’, bagar ‘copper’, šero ‘beer’; Kott/Assan tabat ‘camel’, kulun ‘foal’, araka ‘wine’; Assan talkan ‘flour’, alton ‘gold’; Arin ogus ‘bull’, bugdai ‘wheat’, kajakok ‘butter’, etc. A few Turkic loans even name natural phenomena, e.g., Kott/Assan boru ‘wolf’, attesting to the pervasive Turkic influence on later stages of these languages; cf. Ket qɨ̵̄t ‘wolf’ and Yugh Xɨ̵̄t ‘wolf’, terms presumably inherited from Proto-Yeniseian. 14 The contact situation for Ket and Yugh, the northern Yeniseian languages, is quite different, since these tribes were not in direct association with stockbreeding peoples of the steppes. Rather, the Ket in their taiga home lived in desultory proximity to reindeer-breeding tribes on all sides. The Nenets and Enets groups to the north, as well as the Evenki tribes pushing into the Yenisei watershed from eastern Siberia, tended to be adversarial toward the Ket. Contact was sporadic and generally hostile, with few or no identifiable loanwords into the Ket dialects from Nenets, Enets, or Evenki. A rare exception is soγuj ‘sokui’, an Evenki word in Northern and Central Ket for a type of pullover jacket without a hood (cf. Alekseenko 1967: 138). The situation with the Selkup was different, since the Ket developed friendly relations with this tribe and even exchanged marriage partners after the traditional inter-Ket exogamous phratry system collapsed in the wake of smallpox epidemics. Selkup loans in Ket are somewhat more common and include the ethynonym la’q ‘Selkup’, a word that means ‘friend’ in Selkup, symbolizing the close relations between Ket and Selkup peoples. There are also loans relating to domesticated reindeer (qobd ‘castrated reindeer’, ollas ‘reindeer calf’, kaγli ‘reindeer sled’), with some Ket in the Yelogui River area (near present-day Kellog Village) even adopting reindeer breeding by the early 20th century. Other words shared between Ket and Selkup were more likely borrowed in the other direction, notably Selkup aqlalta ‘guardian spirit image’. This word is only found in the Selkup dialect spoken adjacent to Ket and likely derives from an earlier pronunciation of Ket allɛ́l ~ allalt ‘guardian spirit doll’ (the disappearance of the final -ta, which appears to have been a native Ket nominalizing suffix, gave rise to the final stress in the first variant). Xelimskij (1982: 238-239), conversely, interprets this word as a Selkup loan into Ket which derives from a nominalization of the Selkup verb ‘to amaze’, an etymology unlikely on semantic grounds. A few loanwords in Ket were likely borrowed through Selkup or Turkic and ultimately derive from more distant sources. One is kančá ‘(smoking) pipe’, a word of Chinese origin found in many Native Siberian languages. Another is Ket/Yugh na’n ‘bread’, which might represent a Wanderwort of Iranian origin, though it might just as likely be a nursery word. 15 4. Numbers and kinds of loanwords in Ket 4.1. Introduction The subdatabase for Ket contains 1018 words, alongside 443 gaps, most involving concepts irrelevant or unknown to Ket speakers and therefore lacking any dedicated lexical designation. Most lexical gaps involve items alien to the traditional world of taiga hunter-gatherers. These include exotic realia such as ‘palm tree’, ‘elephant’, ‘beech tree’, ‘kangaroo’, etc., as well as technological concepts or social categories typical of stratified sedentary society: ‘battery’, ‘axle’, ‘judge’, ‘jury’, ‘birth certificate’, and so forth. Other gaps involve cases where Ket lacks a superordinate term that would correspond to a general category typically designated by a lexeme in other languages, such as ‘weapon’, ‘tool’, ‘age’, ‘plant’. A number of the completed entries represent super-counterparts – single lexical items used to express two or more basic meanings. Once example is ba’ŋ, the Ket noun used to refer to the concepts, ‘earth’, ‘land’, ‘soil’, as well as ‘time’. Another is bisɛ́p, a generic word for ‘sibling’ that can be used to mean either ‘brother’ or ‘sister’. Finally, a number of lexical gaps unfortunately result from insufficient information about Ket vocabulary. Among the coded forms in the subdatabase, only 78 show clear evidence of having been borrowed. In most of the remaining 940 cases, there is little or no evidence for borrowing, and the word must be considered as belonging to native Ket vocabulary. While in a majority of these cases, the words in question were recorded by linguists only during the mid 20th century, a comparison of core Ket vocabulary with that of the documented extinct Yeniseian languages (most notably Kott and Yugh) suggests that virtually all basic Ket words are of native provenance. In the case of the clearly borrowed items, the age of most of them can be surmised based of what is known historically about episodes of language contact. The overwhelming majority of clearly attested loanwords (72 out of 78) derive from Russian, with most of these acquired by Ket during the 20th century. Early Russian loans are defined as words incorporated into Ket before the 1930s, when the Ket were forced to settle down in Russian-style villages and began to communicate in Russian on a regular basis. These early loans can be identified on 16 the basis of their more complete phonological adaptation (about which cf. §5 below), or their meanings (i.e., they refer to Tsarist era categories such as ‘priest’). In addition, there are a few cases where early Russian loans into Ket were actually attested during the 19th century. It should be noted that some modern Ket words may ultimately derive from early Turkic or Uralic loans into ancient Yeniseian, though such a possibility is difficult to verify. One such word is Ket qɯ̄nt ‘ant’, possibly associated historically with Proto-Finno-Ugric *kuńće ‘ant’ (Xelimskij 1982: 244). Another is Ket bo’q ‘bag net’, apparently connected with Selkup *pok ‘bag net’ (Alekseenko 1967: 62). In such cases, however, it is not possible to determine with certainty whether we are dealing with a chance resemblance or, in the case of a genuine loanword, to determine the direction or time of borrowing. Conversely, some panYeniseian terms of basic vocabulary, such as ‘stone’ (Ket tɯ’s, Yugh čɯ’s, Kott šiš, Arin kes), are more likely to be the source of early loans into Common Turkic (cf. Proto-Turkic *taš ‘stone’). The dialectal differentiation of the Yeniseian words visà-vis the Turkic form suggest that, if the resemblance is more than simply chance, then it was Turkic that borrowed the word from Yeniseian, presumably from a Yeniseian language with initial *t. In summary, there are no incontrovertible examples of basic Ket content words (body parts, kinship terms, words for basic actions and the like) originating as direct loans from another language. Nor do borrowed nouns, adjectives, or verbs from Russian belong to the core vocabulary. 4.2. Loanwords by semantic word class Table 1 shows the breakdown of loanwords from the four attested source languages into Ket by semantic word class. The decimal values indicate instances where a native synonym exists for a given loanword. Table 1: Loanwords in Ket by donor language and semantic field (percentages) Mongolian Selkup Evenki Chinese Total loanwords Nonloanwords Nouns Verbs Function words Adjectives Adverbs all words Russian 17 12.3 4 6.1 3.5 8.9 0.7 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.1 13.6 4 6.1 3.5 0 9.7 86.4 96 93.9 96.5 100 90.3 The vast majority of loanwords are nouns, which make up about 14% of the total number of nouns in the subdatabase. Loan verbs are much more rare, and are limited to the borrowing of Russian infinitives or nouns incorporated into the Ket verb complex in the morpheme position normally reserved for nominal forms: (da-deld-uγabet ‘she shares it’ (< Russian delit' ‘to share’), da-kerasin-ataγit ‘she rubs him with kerosene’ (< Russian kerosin ‘kerosene’). Therefore, in a sense, even these verb-related loans are nominal in nature. 4.3. Loanwords by semantic field A breakdown of percentages of loanwords in the 24 semantic fields represented in the subdatabase likewise reflects the predominance of Russian loans in comparison to loans attested from other families. 18 Selkup Evenki Chinese Total loanwords Nonloanwords The physical world Kinship Animals The body Food and drink Clothing and grooming The house Agriculture and vegetation Basic actions and technology Motion Possession Spatial relations Quantity Time Sense perception Emotions and values Cognition Speech and language Social and political relations Warfare and hunting Law Religion and belief Modern world Miscellaneous function words Mongolian 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Russian Table 2: Loanwords in Ket by donor language and semantic field (percentages) 4.9 1.5 6.7 3.3 14.6 13 23.1 12.8 10 6 24.1 6.3 2.9 9.9 5.6 13.8 9.7 3.5 30.8 15.4 54.8 8.9 1.8 9.7 4.8 0.4 1.7 1.7 0.2 3.2 0.1 3.2 0.1 4.9 1.5 8.3 3.3 16.5 13 23.1 19.2 11.7 6 24.1 6.3 2.9 9.9 0 5.6 13.8 0 19.4 3.5 30.8 15.4 59.5 0 9.7 95.1 98.5 91.7 96.7 83.5 87 76.9 80.8 88.3 94 75.9 93.7 97.1 90.1 100 94.4 86.2 100 80.6 96.5 69.2 84.6 40.5 100 90.3 As can be seen from Table 2, loanwords are scattered widely across the semantic spectrum. A relatively larger number of loanwords belong to the categories Food and drink (a total of 8 loans), The house (6), Possession (6), and Animals (5). Unsurprisingly, these are all semantic fields involving realia with which the Ket came into regular daily contact only after the sedentarization campaign of the 1930s. Even in these categories, it must be noted, the majority of new items encountered by the Ket after their adoption of a Russian village lifestyle received names based on native Ket neologisms rather than borrowing or even calquing based on Russian, if they received any dedicated nominalization at all. For example, alongside Ket sa’j ‘tea’, a loanword deriving earlier from either Russian čaj or Mongol tsai, other drinks received native Ket nominalizations. Vodka came to be referred to as bɔγul (< bɔ’k ‘fire’ + ūl ‘water’), and coffee was called qʌliŋ ūl 19 (<qʌliŋ ‘bitter’ + ūl ‘water’). The concept ‘guilty’ was interpreted in Ket as saʁan, derived from a combination of native Ket sa’q ‘squirrel’ with the case marker -an ‘without, lacking’, since someone without furs to pay their tax was ‘guilty’ or ‘at fault’ in a legalistic sense. Neologisms of this sort far exceed the actual loanwords. Judging from the dearth of clearly attested borrowings that predate contact with the Russians, resistance to outright lexical borrowing could be regarded as a strong feature of traditional Ket linguistic culture. 5. Integration of loanwords Despite this apparent linguistic conservatism, Ket does contain a fair number of Russian loans. However, very few of these have been fully assimilated to Yeniseian phonology. Many begin with /m/, /n/, or /p/ – sounds not normally found as onsets in native Ket words: mina ‘pig’ (< Russian svinja ‘pig’), nela ‘week’ (< Russian nedelja ‘week’), pamagat ‘to help’ (< Russian pomogat' ‘to help’). Another feature that distinguishes many Russian loans words from words of native Ket provenance is their polysyllabicity. Native Ket nouns tend to be monosyllabic unless each syllable can be associated with a separate morpheme. This is less often the case with Russian loans, many of which are polysyllabic and of course semantically opaque: tɛslá ‘adze’ (< Russian teslo ‘adze’), kurúk ‘hook’ (< Russian kr'uk ‘hook’). A very few recent Russian loans are not integrated at all and even initial consonant clusters, which are impossible in native Ket words. Instead of the more integrated kola ‘school’ (< Russian škola ‘school’), which is encountered in Ket speech, one can also encounter the unintegrated pronunciation škola. Such loans obviously date after the beginning of extensive Ket-Russian bilingualism (after the 1930s). Phonologically non-integrated words of this type tend to be rejected as genuine Ket words by my informants, and their occasional usage as attested by their entry into Werner’s (2003) dictionary might best be regarded as lexical code-switching. But a few, such as škola ‘school’, even in its fully unintegrated pronunciation, were accepted as genuine Ket words. Monosyllabic loanwords receive one of the four phonemic Ket tones. The default tone appears to be the abrupt glottalized tone, which is found in a 20 majority of such words: hɔ’p ‘priest’ (< Russian pop ‘parish priest’). A few take other tones due to some feature of the original phonology. For example, the loanword kōn ‘horse’ (< Russian kon' ‘steed’) received high-even tone, apparently because the final palatalized consonant in Russian served to raise the tongue height in the pronunciation of the vowel to a level found only in high-even tone in Ket words. Only high-even tone allows the mid-high vowel allophones [e], [o], [γ], with these phonemes pronounced as the corresponding allophones [ɛ], [ɔ], [ʌ] in all other prosodic environments. 6. Grammatical borrowing Interestingly, there are no attested instances of grammatical affixes borrowed by Ket from other languages. A number of Ket function words, however, are clearly of foreign origin (§6.2). By far the most striking effect of language contact is what could be called “typological accommodation” (cf. Vajda 2009+), whereby Ket speakers gradually adapted their prefixing morphology to mimic the suffixing structures found in all of the adjacent languages with which they came into contact. Over time, this process profoundly affected the nominal morphology (§6.3.1) as well as productive patterns of finite verb stem creation (§6.3.2). Finally, the gradual change of Ket into a suffixing agglutinative language had the phonological effect of replacing the phonemic tones of monosyllables by wordinitial pitch on the first or second syllable of the resultant polysyllabic word forms. This phonological adaptation will be examined first. 6.1. Prosodic adaptation Under the influence of the root-initial agglutinating languages of Inner Eurasia, the tonal prosody in Yeniseian developed partially into a non-phonemic wordaccent system so that in modern Ket phonemic differences in pitch are largely the domain of monosyllabic words (Vajda 2004, 2008). 21 Ket monosyllabic phonological words contain four phonemic prosodemes. These can be called “tones”, though they actually consist of an amalgam of melody, vowel length, vowel height and tenseness (in the case of mid vowels), and the presence or absence of laryngealization (creaky voice). (1) Phonemic prosodemes in Southern Ket monosyllables tonal vowel length phonation mid-vowel melody (syllable type) type quality sūl high-even half-long neutral tense [e, γ, o] su’l abrupt rising short laryngealized lax [ɛ, ʌ, ɔ] sùl rising-falling long neutral lax [ɛ, ʌ, ɔ] sùl falling short neutral lax [ɛ, ʌ, ɔ] ‘blood’ ‘salmon’ ‘snowsled’ ‘hook’ (closed or open) (closed or open) (creaky) (closed or open) (closed only) In polysyllables, many of which were created by attachment of relational morphemes, distinctions in root prosody generally erode, being replaced by a rise and fall of pitch on the first two syllables that resembles word-initial stress. The degree of prosodic erosion – in other words the degree of clitic-like vs. suffix-like behavior of the relational morpheme being attached – is free to vary to express distinctions in focus: (2) Degrees of prosodic erosion in ōp ‘father’ + da-ŋal ‘from’ focused backgrounded nominalization using the suffix -s ōp-da-ŋal ob-da-ŋal ɔb-da-ŋal-s ‘the one from father’ Disyllabic stems have rising/falling pitch under focus or when pronounced in isolation. In a few, the pitch peak falls on the second syllable, giving the 22 impression of stress on the second syllable. These are marked in our transcription with an acute accent on the second syllable. The much more common syllableinitial prosodic prominence is left unmarked (though it is marked in (3) below for contrast sake). This low-yield distinction in disyllables is likewise eroded by the attachment of relational morphemes: (3) Phonemic contrast in disyllabic stem prosody and its erosion before relational morphemes rising-falling pitch: qɔ́pqun ‘cuckoos’ > qɔ́pqun-di-ŋal rising-high falling pitch: qɔpqún ‘cuckoos’ > qɔ́pqun-na-ŋal ‘from the cuckoo’ ‘from the cuckoos’ The discourse-related replacement of phonemic prosody with a generally noncontrastive word-initial emphasis in polysyllables renders modern Ket phonology closer to that of the surrounding languages. Yeniseian failed to develop vowel harmony, but combinations of stem plus strings of grammatical suffixes or clitics – with only the first syllable nucleus capable of reflecting the language’s full range of phonemic distinctions – organizes polysyllabic phonological words in an analogous fashion. 6.2. Function morphemes Ket has borrowed a few basic function words from Russian, including the conjunctions i ‘and’, a ‘and/but’. There is also the adverb bɛ’k ‘always’ (< Russian vek ‘century’) and the particle qōt (< Russian xot' ‘at least’) which has come to be combined with native Ket question words as a formant creating indefinite pronouns: qōt bisɛŋ ‘wherever’, qōt anɛt ‘whoever’, qōt akus ‘whatever’, etc. Perhaps the most interesting loan particle is Ket bēs ‘without (< Russian bez ‘without’). This particle is preposed to a noun followed by the native Ket morpheme -an, commonly known as the caritive case marker, which already expresses the meaning ‘without’: bēs qim-an ‘without a wife’ [without wifewithout]. The loan particle bēs thus functions as a sort of optional circumfixal 23 element, since unpreposed forms such as qim-an ‘without a wife’ [wife-without] remain entirely acceptable. 6.3. Typological accommodation This section examines how core Yeniseian morphological traits were gradually modified to become more like the suffixal-agglutinating language type of the surrounding peoples. Morphosyntactic development in both the nominal and verbal morphology is examined. I have called this process “typological accommodation” (Vajda 2008), since it represents a sort of grammatical quasicalquing “by design”. Malcolm Ross’s (2001) term metatypy is too strong in this case, since what has occurred in Ket does not represent typological replacement but rather the achievement of a new, unique hybrid between two originally radically different morphological types. Adaptation to the suffixal agglutinating languages of Inner Eurasia affected both the nominal morphology as well as the finite verb string, yet did not involve the borrowing of a single morpheme. 6.3.1. Nominal morphology Ket has developed a system of postposed case markers that resembles the case systems of other Siberian languages, but the case markers themselves are not borrowed from any known language and likely derive from native Ket morphemes. The morphological influence of the surrounding languages on Yeniseian was much farther reaching, and appears to have been well under way even during the time of Common Yeniseian. In this sense, Yeniseian languages belong firmly to the broader Inner Eurasian spread zone with its penchant for suffixal agglutination, despite their stark underlying genetic and typological dissimilarity to the other language families of Eurasia. Shared features include an extensive system of postposed bound relational morphemes, which Vajda (2008) has argued are clitics rather than true suffixes. Yeniseian cases and postpositions are functionally and structurally analogous to the case suffixes and clausal 24 subordinating enclitics found in neighboring Turkic and Samoyedic languages (Anderson 2004). In Yeniseian, however, the morphemes in question show signs of having arisen by coalescence. What are usually described as cases in Yeniseian still pattern phonologically as enclitics rather than true suffixes (Vajda 2008). The system of grammatical enclitics in Yeniseian also shows morphological heterogeneity. One set cliticizes directly to the preceding nominal stem. These include the instrumental, caritive (meaning ‘without’), locative (used only with inanimate-class nouns), and the prosecutive (meaning ‘past’ or through’). In particular, the prosecutive is typically present in North Asian case systems (Anderson 2004). (4) Case markers that attach directly to the noun stem masculine animate feminine animate class ‘god’ locative prosecutive class ‘gods’ ɛs-bɛs inanimate - ‘daughter’ class ‘daughters’ - - ‘tent’ ‘tents’ qus-ka quŋ-ka ɛsaŋ-bɛs hun-bɛs hɔnaŋ-bɛs qus-bɛs quŋ-bɛs instrumental ɛs-as ɛsaŋ-as hun-as hɔnaŋ-as qus-as quŋ-as caritive ɛsaŋ-an hun-an hɔnaŋ-an qus-an quŋ-an ɛs-an The other set requires an augment in the form of a possessive morpheme as connector, analogous to the way possessive noun phrases are constructed. Note that the possessive morpheme is a clitic that tends to encliticize to the preceding word whenever one is available: (5) Possessive noun phrases hun=d qu’s hɯp=da qu’s dɯlgat=na qu’s daughter=POSS.FEM tent son=POSS.FEM tent children=POSS.ANIM.PL tent ‘daughter’s tent’ ‘son’s tent’ ‘children’s tent 25 If there is no preceding word to serve as host, the possessive formant procliticizes to the possessum noun: da=qu’s ‘her tent’. As in possessive phrases, these case-marker augments reflect class and number distinctions of the preceding (possessor) noun: da (masculine class singular), na (animate class plural), di (feminine class singular or inanimate class singular and plural). Three Ket cases require a possessive augment4: (6) Case markers that require a possessive augment MASCULINE ANIMATE CLASS ‘god’ ‘gods’ FEMININE ANIMATE CLASS ‘daughter’ ‘daughters’ INANIMATE CLASS ‘tent’ ‘tents’ ablative ɛs-da-ŋal ɛsaŋ-na-ŋal hun-di-ŋal hɔnaŋ-na-ŋal qus-di-ŋal quŋ-di-ŋal dative ɛs-da-ŋa ɛsaŋ-na-ŋa hun-di-ŋa hɔnaŋ-na-ŋa qus-di-Na quŋ-di-ŋa adessive ɛs-da-ŋta ɛsaŋ-na-ŋta hun-di-ŋta hɔnaŋ-na-ŋta qus-di-Nta quŋ-di-ŋta Postpositions concatenate with case markers to form long agglutinative strings that prosodically represent single words, with a stress on the first syllable: (7) Suffix-like concatenations of relational enclitics in Ket dɛŋ-na-hɯt-ka people-PL-under-LOC hɯp-da-ʌʌt-di-ŋa son-PL-M-on-N-DAT ‘located under the people’ ‘onto the son’ quŋ-d-inbal-di-ŋal tents-N-between-N-ABL ‘from between the tents’ Etymologically, many Ket postpositions are obvious adaptations of body part nouns or other noun roots: -hɯt ‘under’ < hɯ̄j ‘belly’; -ʌʌt ‘on the surface’ < ʌʁat ‘back’; -inbal ‘between’ < inbal ‘gap, space between objects’. The resulting concatenations superficially resemble the strings of suffixes in the neighboring agglutinating Turkic and Samoyedic languages. 4 A fourth possessive-augmented case, called “benefactive”, appears in past grammars of Ket (cf. Vajda 2004): da-ta ‘for him’, di-ta ‘for her’, etc. Recent fieldwork has shown that the “benefactive” is simply a truncated pronunciation of the adessive forms by some speakers: da-ŋta ‘for him’, di-ŋta ‘for her’, etc. 26 6.3.2. Finite verb morphology The most striking morphological feature of modern Ket is its rigid series of verb prefix slots, which stand out starkly against the exclusively suffixing inflectional morphology of other verb systems in western and south Siberia. Modern Ket finite verbs conform to a morphological model consisting of eight prefix positions, an original root or base position (P0), and a single suffix position (P-1): (8) Generalized model of the Modern Ket finite verb P8 P7 P6 subject left base person P4 P3 P2 P1 P0 P-1 subject thematic tense/ 3p- tense/ sub- base animate (serves as or consonant mood inanim- mood ject or (original basic stem in object (originally or 3pl ate object verb root plural shape or animate subj. trajectory subj or prefix) obj. most verbs) P5 subject position) or obj. Two features of modern Ket verb morphology are extremely unusual typologically. First, the configuration of subject/object markers is not determined by an overall grammatical rule, so that agreement morphemes appear in different, and largely unpredictable combinations of the following positions: P8, P6, P4, P3, P1 and P-1. The resultant combinations form two productive transitive subject/object configurations, and five productive intransitive subject configurations (Vajda 2004). Which configuration a given verb requires is determined by idiosyncratic etymological factors rather than general semantic principles and must be listed as a feature of the verb’s lexical entry. Second, the verb’s primary lexical element – its semantic head – occupies either P7 near the beginning of the verb, or P0, near the end, depending on the stem in question. The intervening affixes thus appear as prefixes in some verbs but as suffixes in others. The oldest verbs are invariably root-final, with the semantic head in P0. 27 (9) Examples of archaic root-final verbs with prefixes durɔq ‘he flies’ du8-doq0 [3M.SBJ8-fly0] dibbɛt ‘I make it’ di8-b3-bet0 [1SG.SBJ8-3N.OBJ3-make0] dbiltaŋ ‘he dragged it’ du8-b3-il2-taŋ0 [3M.SBJ8-3N.OBJ3-PAST2-drag0] However, all productive patterns of Ket verb-stem formation require a clearly identifiable lexical element in P7, rendering the original prefixes in the rest of the string as suffixes. Verbs with a clearly prefixing structure, such as those in (9) above, generally belong to the oldest and most basic layers of the language and are perhaps the equivalent of strong verbs in the Germanic verbal lexicon. The semantic interaction between the morphemes in the newer P7 slot and the original verb root slot in P0 is of two distinct types. The first involves genuine incorporation of a noun or adjective form in P7, with P0 still containing a recognizable verb root of some sort, as exemplified in (10). Note that the P8 subject agreement marker in verbs containing a P7 morpheme is a clitic that normally attaches to the preceding word, so that the P7 morpheme regularly stands in phonological verb initial position. (10) Example of incorporation of (a) object noun or (b) instrument noun a. (t)sálarɔp du8-sal7-a4-dop0 ‘he smokes’ 3M.SBJ8-tobacco7-PRES4-injest0 b. (d)donbaγatɛt ‘he stabs me’ du8-do’n7-ba6-k5-a4-tet0 3M.SBJ8-knife7-1SG.OBJ6-TH5-PRES4-hit0 Only about seven P0 verb roots allow object or theme incorporation in P7, and only two P0 roots allow instrument noun incorporation. Incorporating verbs appear to be a new variation on an old model that arose as part of a general typological shift toward root-initial word forms. 28 (11) Incorporating model of modern Ket verb formation P8 P7 P6 P5 P4 P3 P2 P1 P0 P-1 verb anim. subject incor- subject thematic tense/ inanim. tense/ sub- (clitic) porated or mood or subject ject or root sub- noun object 3rd person or object ject animate object consonant mood plural sbj or obj In the remaining productive patterns of Ket verb stem formation, the left base (P7) contains an infinitive form that serves as the verb’s semantic peak, while the original base (P0) contains an eroded verb root denoting generalized lexical aspect or voice categories such as ‘single action transitive’ or ‘beginning of action’. (12) Examples of infinitive-initial verb forms daúsqibit ‘she thaws it (once)’ da8-us7-q5-b3-it0 3F.SBJ8-thaw7-CAUS5-3N.OBJ3-MOM.TRANS0 daúsqabda ‘she thaws it (repeatedly)’ da8-us7-q5-a4-b3-da0 3F.SBJ8-thaw7-CAUS5-PRES4-3N.OBJ3-ITER.TRANS0 Note that the remaining position classes serve the same functions as in prefixing, root-final verb models, except that these slots serve as suffixes in verbs with an infinitive in P7. 29 (13) Infinitive-initial pattern of modern Ket verb formation P8 P7 subject infinitive (clitic) P6 P5 sub-ject them- as semantic or peak atic object consonant P4 P3 P2 P1 P0 P-1 tense/ inanim. tense/ subject eroded verb 3 animate object or root as affix anim. object of aspect or plural mood or p subject or sbj or obj mood subject transitivity The realignment of the phonological verb’s semantic head to the extreme left edge served to accommodate the original Yeniseian prefixing structure to the pattern of suffixal agglutination prevalent in all of the neighboring languages. Yet no actual affixes were borrowed in this process. Nor did any change occur in the order or function of the original prefix slots, which instead simply took on the appearance of suffixes. There are only two types of morphemes in the modern Ket verb system that can be identified as having been borrowed. These are a few Russian infinitive forms along with several loan nouns that can be incorporated as instrument or object. (14) Ket verb forms containing loanwords in P7: (a) infinitive, (b) instrument noun a. (d)lečitbɔγavɛt ‘he cures me’ du8-lečit7-bo6-k5-a4-bet0 3M.SBJ8-cure7-1SG.OBJ6-TH5-PRES4-VERBALIZER0 b. (t)kɛrasinatakit ‘he rubs him (a dog) with kerosene (precaution against fleas)’ du8-kerasin7-a6-t5-a4-kit0 3M.SBJ8-kerosene7-3M.OBJ6-TH5-PRES4-rub0 In summary, it appears that during the centuries of development of Ket before the arrival of the Russians in Siberia, certain areally dissonant features of Yeniseian morphology gradually underwent typological accommodation to Samoyedic and Turkic languages. This involved the innovation of root-initial verb forms and the development of a system of case markers. It also affected the 30 phonemic prosody, which became eroded in longer, suffixal-agglutinative word forms. Modern Ket, the best documented Yeniseian language, provides the best available illustration of how these traits came to mimic the prevailing morphological and phonological patterns of the surrounding languages without actually being replaced. The resulting uniqueness of Modern Ket morphology is in no small measure a product of this intricate process of structural hybridization. 7. Conclusion Ket as well as its extinct relatives appear to be languages that are rather resistant to outright borrowing of words and morphemes. The most significant exceptions came during the initial phase of language shift as speakers became bilingual in a superstrate language. In the case of 20th century Ket and Yugh, the superstrate was Russian, while South Siberian Turkic dialects appear to have played the same role in the final decades of Kott, Assan, Arin and Pumpokol. These late loans tend to be only partly integrated to the phonologies of their recipient languages. Still, despite today’s rapid pace of language loss the Ket continue to be resistant to outright borrowing. Metaphoric neologisms made on the basis of native Ket morphemes (e.g., bɔγul ‘fire water’, and the like) remain the preferred method of concept naming even in the closing years of Ket as a viable form of communication. Outright grammatical borrowing is likewise the exception rather than the rule. While there are a small number of function words that represent recent loans from Russian, not a single bound morpheme in Ket can be identified as borrowed from another language. Much more striking is the process of “typological accommodation” that has gradually, over the centuries, shifted the morphological profile of Ket from a prefixing language to one that places the lexeme’s semantic head word-initially. This process, together with the seemingly contradictory feature of resistance against borrowing actual morphemes and lexemes, is probably connected with the traditional social situation in which Ket-speaking groups lived. Selective bilingualism with outsiders, along with induction of marriage partners from other groups, filtered out most outright borrowing, yet 31 gradually led to a sort of morphosyntactic calquing by design that rendered Ket morphology into a unique hybrid of traditional prefixing structures expressed root-initially. Judging from certain basic commonalities in Yeniseian case markers and verb stem patterns, typological accommodation must have begun in Common Yeniseian, though it has played itself out differently in each of the daughter languages. Abbreviations used in the verb morpheme glosses ANIM animate class F feminine ITER multiple action M masculine MOM single action neuter (=inanimate) class N OBJ object agreement affix PL plural SG singular SBJ subject agreement TH thematic consonant TRANS transitive References Alekseenko, E. A. 1967. Kety: ètnograficheskie očerki [The Ket: ethnographic studies]. Leningrad: Nauka. Anderson, Gregory 2003. “Yeniseic languages in Siberian areal perspective”. Sprach-typologie und Universalienforschung 56.1/2: 12-39. Anderson, Gregory 2004. “The languages of Central Siberia”. Languages and prehistory of Central Siberia, ed. by Edward J. Vajda. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Pp. 1-119. 32 Castrén, M. A. 1858. Versuch einer jenissej-ostjakischen und kottischen Sprachlehre, Sankt-Peterburg: Imperatorskaja Akademija Nauk. Donner, Kai. 1955. Ketica: Materialien aus dem Ketischen oder Jenisseiostjakischen. Helsinki: Finno-Ugric Society. Dolgix, B. O. 1960. Rodovoj i plemennoj sostav narodov Sibiri v XVII veke [The clan and tribal composition of Siberian peoples in the 17th century]. Moscow: Akademija nauk. Dul’zon, A. P. 1961. “Slovarnye materialy XVIII v. po ketskim narečijam [18th century dictionary materials on Ket and related dialects]”. Uc&enye zapiski Tomskogo gos. pedagogičeskogo instituta 19:2.152-89. Tomsk: TGPI. Georg, Stefan. 2007. A descriptive grammar of Ket. Part I: introduction, phonology and morphology. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental. Kotorova, E. G., editor-in-chief. (2009+). Bol’šoj ketsko-russkij slovar’ [Comprehensive Ket-Russian dictionary]. Tomsk. Krejnovič E. A. 1969. “Medvežij prazdnik u ketov [The Bear Festival among the Ket]”. Ketskij sbornik: mifologija, ètnografija, teksty. Moskva: Nauka. Pp. 6-112. Krivonogov, V. P. 1998. Kety na poroge III tysjac&eletija [The Ket on the threshold of the 3rd millennium]. Krasnoyarsk: RIO KGPU. Krivonogov, V. P. 2003. Kety: desjat’ let spustja [The Ket: ten years later]. Krasnoyarsk: RIO KGPU. Ross, Malcom. 2001. Contact-induced change in Oceanic languages in North-West Melanesia. Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance, eds. A. Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. 134–166. Vajda, Edward J. 2001. Yeniseian peoples and languages: a history of Yeniseian studies with an annotated bibliography and a source guide. Curzon Press: Surrey, England. Vajda, Edward J. 2004. Ket. Munich: Lincom Europa. Vajda, Edward J. 2008. “Head-negating enclitics in Ket”. Subordination and coordination strategies in the languages of Eurasia, ed. by Edward J. Vajda. (Current issues in linguistic theory, 300). Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Pp. 177-199. Vajda, Edward J. 2009+. “Yeniseic substrates and typological accommodation in central Siberia”. The languages of hunter-gatherers: global and historical 33 perspectives, ed. by Tom Güldemann, Patrick McConvell & Richard A. Rhodes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Vajda, Edward & Heinrich Werner 2009+. Etymological dictionary of the Yeniseic languages. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. Verner, G.K [=Heinrich Werner]. 1990. Kottskij jazyk [The Kott language]. Rostovna-Donu: Rostov University. Verner, G. K. 1993. Slovar’ ketsko-russkij/russko-ketskij s&kol’nyj slovar’ [KetRussian/Russian-Ket dictionary]. Leningrad: Proshves&c&enie. Werner, Heinrich. 2003. Wiesbaden Harrassowitz. Vergleichendes Wörterbuch der Jenissej-Sprachen. Werner, Heinrich. 2005. Die Jenissej-Sprachen des 18. Jahrhunderts. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. Werner, Heinrich. 2006. Die Welt der Jenissejer im Lichte des Wortschatzes: zur Rekonstruktion der jenissejischen Protokultur. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. Xelimskij, E. A. 1982. “Keto-Uralica”. Ketskij sbornik: antropologija, ètnografija, mifologija, lingvistika, ed. by E. A. Alekseenko et al. Leningrad: Nauka. Pp. 238251. Xelimskij, E. A. 1986. “Arxivnye materialy XVII veka po enisejskim jazykam [18th century archival materials on Yeniseic languages]”. Paleoaziatskie jazyki, ed. by P. Ja Skorik. Leningrad: Nauka. Pp. 179-213.