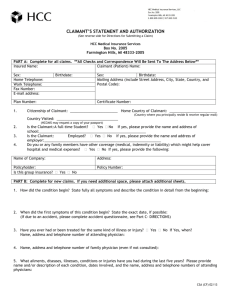

CILA CONFERENCE DIMINUTION IN MARKET VALUE PAUL

advertisement

CILA CONFERENCE DIMINUTION IN MARKET VALUE PAUL HANDY – CRAWFORD & CO JAMES DEACON – BEACHCROFT LLP The Danger Cash settlements are always open to critical analysis by a third party loss adjuster or solicitor when pursuing a subrogated recovery and they must be agreed with eyes wide open to any impact that they may have further down the line. It will not always follow that the basis upon which you may agree a cash settlement with the Insured will end up being the same basis upon which a Court will calculate damages in a subrogated recovery. For example, where an Insured decides not to use the money it receives from insurers to rebuild its fire damaged building and decides to sell the building instead, diminution in value will be the correct measure of loss. Insurers could end up being left significantly out of pocket following the subrogated recovery. At the risk of giving you a conclusion right at the outset of this session, the key is to look at the long term resolution of the matter rather than separately compartmentalising the claim under the policy and the subrogated recovery. That is where danger lies. Having highlighted one of the pitfalls surrounding diminution in market value, I thought it would be useful to go back to basic principles and then try to elicit some general rules from the case law as to how Courts assess the measure of a Claimant's loss (i.e reinstatement v diminution in value). The Policy Let us then start with property policies. The settlement provisions under a property policy may typically provide insurers with 3 options, namely: to pay the value of the property insured at the time of its loss or destruction, or to pay the amount of the damage, or at the insurer's option, to reinstate. Reinstatement v paying costs of Reinstatement Reinstatement clauses have two main objectives. Firstly, if different interests in the same subject matter have been insured under various policies issued by a number of insurers, it is possible that the aggregate sum payable under the various policies will exceed by a significant amount the cost of full reinstatement. It is in the interests of the various insurers to agree amongst themselves to reinstate the property, sharing the cost proportionately between themselves. Secondly, a reinstatement clause is a significant anti-fraud device; an insured who is tempted to set fire to or otherwise destroy his own property in an attempt to obtain its doubtless inflated cash value from insurers will have no incentive to Page 1 of 13 5582236_1.DOC do so, if all that he will receive is the same subject matter with repairs. Where the possible fraud has already been committed, it remains a useful device to test the water with the insured. A discretion to reinstate also arises under s 83 of the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774 where, again, fraud by the insured is suspected. Section 83 also imposes an obligation on insurers to reinstate a building where so requested by someone other than the policyholder with an interest in the building (e.g. where a tenant requests his landlord’s insurers to reinstate the building following a fire). This provision was recently considered by the Law Commission in the ongoing review of insurance contract law with a view to its being repealed but only 14 responses were received on the topic and the consensus was that the provision be retained. It may be worth here clarifying the distinction between true reinstatement and paying the costs of reinstatement to the Insured. When an insurer elects to reinstate under the third bullet point above, that decision is binding on both parties and an insurer cannot change his mind simply because his election proved a bad one. Further, the contract of insurance then becomes enforceable as if the insurer had entered into a building contract with the insured and may result in the insurer paying out more than the maximum limit under the policy. (This is worth distinguishing from the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act where an insurer is not required to pay out more than the limit of indemnity under the policy). Paying the costs of reinstatement on the other hand does not involve insurers electing to carry out the works themselves. Where an insurer pays to his insured the cost of reinstatement, the insured cannot receive more than the relevant limit of indemnity and insurers are not liable for any defects within the repair works. Tonkin v UK Insurance (2006) EWHC 1120 (TCC) provides useful guidance as to the reinstatement options open to an insured and, more to the point, what they cannot claim for. The property here was a barn, the claimants' home, with a smaller barn next to it which the claimants used as an occasional art gallery. They did not have planning permission to turn it into habitable accommodation. The barn but not the gallery was destroyed by fire. The claimants instructed a firm of surveyors to draw up a reinstatement scheme, which was not accepted by insurers. The claimants claimed for a kitchen for which the insurance company had already paid out and had used money from insurers to buy underfloor heating, which was an item that had been excluded from the schedule of works approved by insurers. It was found that the proposed scheme was not a basic reinstatement but included significant changes and improvements. It therefore could not be used as an accurate assessment of the claimants' claim against their insurers. The scheme was also so inadequately documented that, even if the scheme had been appropriate, it would not have formed a reliable basis on which to assess damages. Page 2 of 13 5582236_1.DOC What the decision went on to do was set out the three possible approaches to reinstatement claims and the best practice procedures to follow: 1. An insured may decide to reinstate to a layout and condition that mirrors as closely as possible what the property was like before it was damaged. If this option is followed a detailed specification together with a full set of drawings should be prepared to identify the reinstatement works in as much detail as possible. These should then be approved by the insurer. At the same time, a budget cost should be prepared so that the costs are known, in broad terms, to both parties. Once the documents have been approved, they should be sent out for tender. The only likely complication will be if the local authority requires particular materials or features to be incorporated within the proposed works, which will give rise to additional cost. Whether this is an insured cost will depend on the terms of the policy (i.e where involuntary betterment is included). 2. An insured may take advantage of the destruction of the building to make certain minor changes to improve on what had been there before. If this option is chosen, it is essential that the insured makes it plain to insurers and the improvements need to be clearly identified. The specification and drawings will incorporate the improvements. Again, they will need to be approved by the insurer and if the improvements are relatively minor, they may be prepared to bear the cost of them. Otherwise, they will need to be paid for by the insured. It is at this point that I would flag up serious consideration of how the subrogated recovery will be pursued and any additional costs handled. 3. Finally, an insured may take advantage of the opportunity and make significant changes to what was there before. If this option is chosen, the insured cannot expect the insurer to pay for those changes. The insured must again make it abundantly clear what they are intending to do, both to insurers and in the supporting documentation and it needs to be clear for both the insured and the insurer which works will be paid for by the insured and which by the insurers. What the insured must never do is choose option 2 or 3 and either attempt to persuade the insurer that they have chosen option 1 or wait for the insurer to spot the improvements. This could amount to fraud and taint the whole claim. Page 3 of 13 5582236_1.DOC Paying the 'amount of damage' Where the policy requires an insurer to pay the amount of the damage, the critical question is how do you assess the amount of damage that the insured has suffered; by reference to the cost of reinstatement, diminution in value or some other yardstick? We have already seen that, in some cases the amount of damage will equate to what it will cost the Insured to rebuild substantially the same building as was there before. In Leppard v Excess Insurance (1979) I WLR 512, the insured's cottage was destroyed by fire. The sum insured was £14,000. The reinstatement value (i.e. the cost of rebuilding) was £8,000. The market value just prior to the fire was £4,500. The residual value of the land after the fire was £1,500. The market value was known as the insured had intended to sell. On this basis, they only recovered £3,000, the diminution in market value, i.e the difference between the value which the cottage had prior to the fire (£4,500) and the residual value post fire (£1,500). Many policies will contain quite detailed provisions as to how the measure of indemnity under the policy will be calculated. Very often, if the primary measure of settlement under the policy is cost of reinstatement, you will find an alternative basis of settlement clause, entitling the insured to no more than the value of the property insured in the event that the insured decides not to reinstate or delays in reinstating. The different clauses which may be found in policies is beyond the scope of this talk. The key point to take away is that the amount which insurers may be contractually obliged to pay to their insured under the policy will not always be the same as the measure of damages which may ultimately be recoverable from a third party in a subrogated recovery action. Once a payment has been made to the insured, even on a reinstatement basis, the insured is entitled to use the monies as he likes. He cannot be forced to reinstate. This however does shape the way that consideration is given to the appropriate measure of damages in a subrogated recovery as we shall see in a minute. It is this entitlement to use the monies in any way which can cause problems in pursuing a subrogated recovery on a reinstatement basis. Measures of damage available on a subrogated recovery This highlights then the crux of the debate on diminution in market value between parties on a subrogated recovery. The third party may argue that its liability to the insured is limited to diminution in market value, particularly if faced with a reinstatement or other larger settlement by insurers to their insured. It is increasingly easy today for both parties to find out if the property has been on the market with the help of the likes of primelocation.com and other property search websites and what the value Page 4 of 13 5582236_1.DOC of the property is. On a subrogated recovery, the approach taken by the Courts to assessing the measure of damage appears to differ depending on whether the damage is to buildings or chattels (e.g goods, plants, machinery etc.). Damage to Premises As a rule of thumb, the basic measure of damages for a building is the cost of reinstatement. As Judge Hicks put it in Stow & Co Ltd v Lawrence Construction Ltd (1994) 40 Con LR 57. "the basic rule points to the cost of reinstatement as the primary measure of damage for injury to real property." So, if A negligently burns B’s house down, the starting point is that B should be entitled to recover an amount to compensate him for what it will cost to rebuild the house. If a defendant in a subrogated recovery wants to limit the claim to diminution in value, then he must show good reason to do so. The object of any award of damages is to put the person who has suffered the loss in the position they would have been in had the loss not occurred (or in a claim for breach of contract, had the contract been properly performed). So if the defendant can show that the claimant has not and will not actually repair the building (e.g. if the claimant puts his house on the market, or the property was always going to be redeveloped or demolished or for some other reason had a relatively short lifespan), diminution in market value is likely to be the correct measure of damages. When pursuing a subrogated recovery, you must be able to substantiate the amount of damages claimed and provide documentation in support. So if you are claiming for repair costs, invoices substantiating the costs of repairs will be required, together with a report from a QS. If diminution in market value is the correct measure of loss, then a report from a valuer will be required. It is worth noting as well that the measure of damage is to be ascertained at the date of the loss and not at some later date such as when tenders for reinstatement are subsequently received. In relation to domestic property, any homeowner who genuinely intends to rebuild is likely to recover on a reinstatement basis. It would seem unreasonable to argue in those circumstances, for example, that they should abandon the property, sell it for what they can and buy another somewhere else, and only recover diminution in value. Similar principles based on a genuine intention to rebuild have been applied to commercial premises, as for example in Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd v Wayne Tank & Pump Co Ltd (1970) I QB 447. There, a factory was destroyed by fire due to a faulty heating system installed by the defendants. Although the claim was brought in contract, the same principles apply to the measure of damages in tort. The Page 5 of 13 5582236_1.DOC factory owner had to rebuild its factory and ended up with a new and better factory. The defendant argued that the appropriate measure of loss should be the diminution in value of the original building after the fire, otherwise the claimant would be better off than it was prior to the fire. The factory owner successfully claimed the cost of rebuilding the property, it being pointed out that this was necessary to keep the business going and to mitigate any ancillary claim for loss of profit. A key issue therefore is whether there is a long business association with the premises which makes it reasonable to repair them. The court pointed out that a factory is not like a car. You cannot go out into the market and readily buy an identical second hand factory. It was reasonable for the claimant to rebuild a new factory and he had not acted extravagantly in rebuilding it to keep his business going. The costs of rebuilding were awarded rather than diminution in value. It is always worth asking what use the insured had put the property to immediately before the loss. For example, where there is a particularly ornate building, a distinction needs to be drawn between an insured who wishes to use the premises in their actual pre loss state - where the loss will be the building in its peculiarly ornate condition - and an insured who would be content with a modern equivalent. An example of the former arose in Reynolds v Phoenix Assurance (1978) 2 Lloyd's Rep 440. An old maltings in Suffolk was destroyed by fire. It was the intention of the insured to carry on trading at these premises. Whilst loss adjusters and insured agreed reinstatement, it was not approved by insurers. It was held that diminution in market value was not appropriate as it would be very difficult to establish a value for the premises as there was no ready market for buildings of that type. It was also held that indemnity based on an equivalent modern replacement was "inappropriate" and so reinstatement was the correct measure of damages. An example of a modern equivalent being the correct measure of damages can be found in Exchange Theatre v Iron Trades Mutual Insurance (1983) I Lloyd's Rep 674 where a Victorian hall was being used as a bingo hall and disco but where the Victorian nature of the building was not important. I should perhaps flag up at this stage that it is not simply the case that there is a direct choice between diminution in market value and reinstatement (either of the original building or a modern equivalent). It may well be appropriate to measure loss in another way, for example by reference to the costs of relocation and we shall come to this in more detail later. Exceptions to the Rule – Where is Diminution in Value appropriate? Reinstatement is unlikely to be the right measure of damages if it can be argued that the claimant did not intend to keep the premises in their original state or if it is not possible to restore them. The first situation arose in both Hole & Sons Ltd v Harrisons of Thurnscoe Ltd (1973) I Lloyd's Rep Page 6 of 13 5582236_1.DOC 345 and Taylor v Hepworths Ltd (1977) I WLR 659. In both cases the owners were intending to demolish the buildings and redevelop the land prior to the loss. In both cases the claimants were denied the cost of rebuilding and had to be content with diminution in market value. In Taylor v Hepworths, the premises was a disused billiards hall in a redevelopment area. On the evidence, the Claimants only valued the premises and the land upon which it stood for its development value. The claimants suffered loss in that essential remedial and safety work had to be carried out in the sum of £3,000, but they also claimed £28,000 for the reinstating of the hall. It was held that the £28,000 could not be recovered from the defendants in the subrogated recovery action (despite having been paid out by insurers to the claimants) and in fact the remedial costs were set off against similar costs which the claimants would have had to incur in any event in clearing the site had they redeveloped it. The same issue arises where the insured did not intend to keep the premises at all and indeed may have had the property on the market at the time of the fire, as was the case in Leppard. The same principle applies where rebuilding cannot be carried out, for example if restoration is forbidden on environmental grounds or needs planning permission that would not be available. Reasonableness and the Third Way Determining the correct measure of damages therefore all boils down to looking at the particular circumstances of the case, what the claimant’s intentions are and what is reasonable. Claimants must also act reasonably to mitigate their loss. To complicate matters, sometimes the court will not choose between diminution in value and reinstatement as the only two means of assessing the claimant’s loss. The court sometimes chooses a third way, where expenditure incurred by the claimant is reasonably required to mitigate other losses. In Dominion Mosaics Ltd v Trafalgar Trucking Ltd (1990) 2 All ER 246, the claimant's business premises were gutted by fire caused by demolition contractors. The claimants were faced with three options. Firstly, rebuilding the premises, which amounted to some £570,000. The defendants argued that the damages should be confined to the diminution in market value of the damaged building, which was only £60,000. The claimants, however, took a third way, selling the premises and relocating, taking on a new lease at short notice for £390,000. It was argued that the diminution in value was wholly inadequate as it was not sufficient to obtain other premises in which to carry on its business. £390,000 was needed for the new lease. This was also far less than rebuilding at £570,000. Moreover, since loss of profits whilst the business hung fire would have been about £300,000 per year, it was imperative to act quickly. It was therefore held that the cost of the relocation at £390,000 was the correct measure of damages. Page 7 of 13 5582236_1.DOC Similarly, the case law dealing with landlords may be read as leaning to the position that where rental property is damaged, the reasonable course for the owner will often be to cut their losses, sell and reinvest rather than incur the greater expense of restoration. This is however not an absolute rule. If the damaged property is not merely an investment vehicle but rather part of an ancestral estate and the estate owner is under a legal or moral obligation to the tenant to keep it in repair, he may well act reasonably in doing so. Betterment Relocation or rebuilding also raises the issue of betterment, as the claimant may end up with better quality or larger premises. Such betterment is usually however ignored. In Dominion Mosaics it was reasoned by the Court of Appeal that although the building was 20% larger than the previous one, this betterment had been forced on the claimant and it would be unfair to penalise them as a result. It was not a case of a rebuilding deliberately incorporating enlargement, but a question of finding some existing premises which most nearly matched the claimants' requirements. Further, against the extra floor space, there would have to be considered the saving in lost profits and the need to adapt and modernise the premises which were not purpose-built for them, which had not been claimed. This is not a given in every case however and care should be taken to ensure that the insured is not choosing an improved property when other roughly equivalent ones are available. In those circumstances, there is much to be said for making a deduction for the betterment. This is not a precise science. In Voaden v Champion (2002) I Lloyd's Rep 623, a vessel and the pontoon to which it had been moored were both lost as a result of the negligence of the defendant. The measure of damages for the pontoon was valued at £16,000 on the basis that the cost of a new pontoon was £60,000 and would have had a life of 30 years, whereas the actual pontoon had a remaining life of only 8 years. The appropriate award was therefore 8/30 x £60,000. So, the anticipated life span of a building may be a relevant factor. Assessing diminution in value Where the appropriate measure of loss is diminution in value, evidence needs to be obtained to demonstrate what value the land and buildings had immediately prior to the loss, as against their value immediately after the loss. Such evidence will usually take the form of a report from an expert valuer/surveyor. There may be cases in which the value of the property immediately after a loss is in fact greater than its value prior to the loss. For example, a cleared site after a fire with planning permission may, in some areas of the country, be worth more than the site with an old building on it prior to the fire, if planning permission would not have been given to change the building prior to the fire. Page 8 of 13 5582236_1.DOC In calculating the value of a building immediately prior to a loss, it is appropriate to take into account the claimant’s intentions with regard to the property and its potential development value. In Farmer Giles v Wessex Water Authority [1990] 18 EG 102, the wall of the claimant’s building collapsed into a river. The cost of rebuilding the wall came out at a ridiculously high figure of £155,000. Conversely, the diminution in value of the site, as it was, would only have been £10,000. The building had been about to be redeveloped and refurbished for commercial purposes, prior to the loss. So, whilst diminution in value was a more appropriate measure of settlement than the cost of reinstatement, the Court of Appeal determined that it was appropriate to take into account the potential development value of the land (given that that was the claimant’s intention prior to the loss), in calculating its true value prior to the loss. Having carried out that exercise, the court ended up awarding £34,000 (which effectively reflected a capitalised sum calculated on the basis of the amount of rent which could have been achieved had the property been developed, less the probable cost of re-developing the property to realise that potential). Impact on Loss of Rent Claim It is perhaps also worth mentioning that if the Court concludes that diminution in value is the appropriate measure of loss on a subrogated recovery action, this may impact upon the loss of rent (if any) which the Claimant can also recover. Measuring the amount of damage to a building on a diminution in value basis does not preclude a claim for loss of rent, but the period over which loss of rent may be claimed may be much shorter than that used to calculate rental losses under the policy (eg if loss of rent under the policy is calculated by reference to the length of time it would take to reinstate the building). Damage to Chattels (machinery/plant/goods etc.) The measure of damages for damage to or destruction of goods is their diminution in value. Diminution in value in this context means: (a) The market value of the goods at the time and place of their destruction (where the goods are totally destroyed); Page 9 of 13 5582236_1.DOC (b) The cost of repairs where goods have only been partially damaged and it is reasonable to effect repairs (i.e. if it is cheaper to buy a replacement on the market and sell the damaged goods than to repair, true diminution in value is the correct measure). However, where the claimant intends to replace the items, and the difference between the sale value before and after the loss would not be sufficient to enable them to do so and it is reasonable to reinstate, then diminution in market value is not appropriate and the measure of damages should be assessed by reference to the cost of replacing the items. The differing measures of damages can be seen in the following cases. In the Maersk Colombo (2001) EWCA Civ 717, a ship struck various port side cranes. The claimants sought the reinstatement value of the cranes of £2.3m, whereas the defendants argued that the appropriate measure of damages was the resale value of the crane just before the incident, namely £665,000. On the facts, 2 new cranes were being delivered in any event shortly after the incident and there were internal memos discussing the sale of the cranes. The reinstatement costs were so high as a second hand crane would have had to be purchased and modified in the US and transported from there to Southampton at a cost of £1.7m. The defendant’s approach to quantification was preferred. In Dominion Mosaics, there was also an issue about the measure of damages for some "paternoster" machines which were designed to accommodate carpets in a showroom so that they could be automatically rotated. Eleven were purchased by the claimants for £13,500 and were destroyed in the fire. This was, however, a unique price as they had been bought as display items from an exhibition at Olympia. The cost of replacement was £65,000. It was held on appeal that the cost of replacement was the correct approach and that the fact that new machines had not been bought yet (due to lack of finances) was not relevant. (It may also be of interest that the court noted that no other figures were put forward as a mid way between the £13,500 and £65,000 – the suggestion being that there may have been some more flexible middle ground that the court might have been interested in pursuing. For example there was no mention of second hand machines or any other reasonable approach). Where diminution in value is the appropriate measure of settlement, it will be easy to assess the market value of the goods concerned at the time and place of their destruction, where there is a readily available second hand market to replace what has been lost. However, where there is no market available to replace such goods, a problem of betterment will often arise, because there will be no automatic market mechanism for measuring the loss. In physical terms, the only way for the claimant to replace the lost item is to buy a new replacement. But, in the case of goods which have a much shorter life span than buildings, the proper approach is to make a fact specific review of what the claimant has lost in financial terms and try to put a figure on it (i.e. making a deduction to reflect betterment). Page 10 of 13 5582236_1.DOC In Voaden v Champion (2002), the Court of Appeal said that: “In such circumstances the test of reasonableness has an important role to play. The role goes further than the proposition that replacement from new has to be absurd for it to be rejected as the measure of loss. The loss has to be measured and where what is lost is old and second hand and coming towards the end of its life, it is not prima facie to be measured by the cost of a brand new chattel, even where the market cannot supply a close replica of what has been lost; and where such a measure would not be a reasonable assessment of what has been lost, it should not be used … Damages ought to be reasonable as between claimant and defendant”. So, in that case, as we have seen, where the claimant had lost a pontoon, which would have cost £60,000 to construct, the court awarded only £16,000, on the basis that a new pontoon had a life span of 30 years, whereas the actual pontoon only had a remaining life of 8 years. Finally, I will leave you with a recent decision. In Aerospace Publishing v Thames Water (2007) EWCA Civ 3 a flood destroyed the claimants' valuable photographic archive which was essential for its business. As ever the argument was whether market value or reinstatement applied. The Court of Appeal held that the cost of reinstatement was the correct measure of loss. The court observed though that it would be wrong to award the cost of reinstatement if: The claimants were about to go out of business There was no prospect of the archive being used in future publications The claimants' income would be similar with or without the archive. Conclusion Where then does this leave us? It all boils down to reasonableness. What I have tried to do, however, is set out a few propositions which might guide your investigations when considering whether diminution in market value or cost of reinstatement should be the guide as to what might be recovered on a subrogated recovery. 1. The aim is to put the claimant in the position they would have been in had the incident not occurred (or in the case of a claim for breach of contract, to put the claimant in the position they would have been in had the contract been properly performed). The quantification of damages is therefore a question of fact. 2. Common to the law of tort and contract are the principles that a loss is only recoverable if it is caused by the breach of duty or contract and it could not reasonably have been mitigated. Page 11 of 13 5582236_1.DOC 3. The amount of damages should be reasonable as between claimant and defendant. The claimant should not find himself out of pocket (and incurring expenditure which he would not have been put to), had the defendant not breached his duty. Conversely, the claimant should not be awarded a significant windfall or additional benefit, which he would not have received, had the defendant not breached his duty. 4. Cases where a claimant recovers more than he has actually lost, as will happen where betterment occurs without any new for old deduction, ought to be exceptional. 5. Recognised examples of such exceptions seem to relate primarily to: Damage to buildings (which would not be expected to have a short life span) where the claimant reasonably intends to reinstate the property; and Destruction of crucial plant or equipment where the cost of purchasing new equipment is necessary as a cost of mitigation, to prevent the claimant’s business collapsing or so as to mitigate a claim for loss of profits. 6. So far as buildings are concerned, the usual measure of damages will be the cost of repair or reinstatement. However, diminution in value will be the appropriate measure, where: 7. The claimant has no genuine intention to repair the buildings; The property was on the market prior to the loss; The claimant was intending to demolish or redevelop the premises prior to the loss; or There is some other reason to think that it will not be possible to rebuild the property. There will sometimes be a third appropriate measure of damages where buildings have been lost or damaged; the claimant may be awarded the costs of purchasing new premises elsewhere, if that is a step which has effectively been taken by the claimant to mitigate other losses to his business. It follows, therefore, that whether the dispute relates to domestic or commercial properties may be a relevant factor. 8. Where goods are destroyed, the normal measure of damages will be the market value of the goods at the time and place of their destruction. 9. Where goods are damaged, the normal measure of damages will be the cost of repairs, but only if it is reasonable to effect repairs (if it is cheaper to buy a replacement on the market and Page 12 of 13 5582236_1.DOC sell the damaged goods, than to repair, diminution in value is the correct measure of loss). 10. The age and availability of second hand markets for goods, machinery and plant etc. will be relevant factors to take into account when assessing the value of the loss suffered by the claimant and the extent to which deductions should be made to reflect betterment. But, summing it all up, the essential question is "what loss did the claimant really suffer?" and which measure of damages should be used to end up with a figure that most closely equates to that loss. Scenarios I started this talk by saying that, when you are adjusting a claim, it is prudent to keep an eye on any prospective recovery action, when making decisions as to how to settle the insured’s claim under the policy. It may be worth highlighting a few examples of how decisions taken on the adjustment of a claim can impact on the recoverability of damages in any subrogated recovery. 1. Let us say the insured’s commercial building is destroyed by fire. The insured tells you that it will rebuild the premises, but that because of cashflow requirements, it needs a quick cash settlement. The costs of reinstatement are likely to be £500,000. The diminution in value is £200,000. You authorise insurers to pay a cash settlement of £350,000, representing a saving to them of £150,000 on the costs of reinstatement. The insured subsequently retains the £350,000 and sells the premises. In a subrogated recovery against the person who negligently caused the fire, the correct measure of loss would be diminution in value i.e. only £200,000. 2. If we take the same factual scenario as example 1, but assume that the insured instead uses the £350,000 to put towards the rebuilding of the property. The insured gets a friend who is a builder to rebuild the premises at a knock-down rate for only £300,000. In the subrogated recovery, the correct measure of damages is the cost of reinstatement. The amount recoverable will be £300,000, since that is the sum which has actually been spent on repairs and not £350,000 (the amount which insurers paid to the insured). 3. Let us assume that within the insured’s building there were several machines which were destroyed in the fire. One of those machines is 10 years old and is coming to the end of its natural life. It is not a critical part of the insured’s business. The cost of purchasing a new equivalent machine is £10,000. The realistic market value of the old machine at the end of its life is £1,000. The insurance policy entitles the insured to the cost of replacing the machinery on a new for old basis. The insured actually purchases a new replacement machine for Page 13 of 13 5582236_1.DOC £10,000 and that is the amount that insurers are correctly advised to pay under the terms of the policy. In the subrogated recovery action, however, it is likely that diminution in value would be the correct measure of damages and a recovery of only £1,000 would be made. 4. Assume the same scenario set out at (3) above, but that the insured does not in fact replace the machine, but simply takes a cash settlement. In those circumstances, you should check the insurance policy, to see if there is an alternative basis of settlement clause which would only entitle the insured to diminution in value under the terms of the policy. Page 14 of 13 5582236_1.DOC This paper is published on a general basis for information only and no liability is accepted for errors of fact or opinion it may contain. Professional advice should always be obtained before applying the information to particular circumstances. © Beachcroft LLP 2010 www.beachcroft.com