SMTQ Vietnam evaluation final 18 Nov 2011

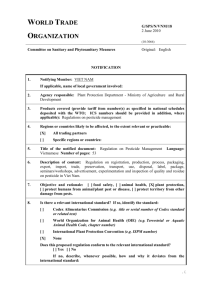

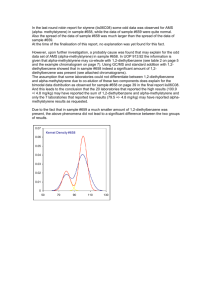

advertisement