institutional food purchasing

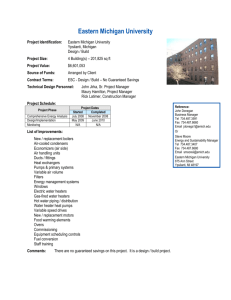

advertisement