Dials and Channels

advertisement

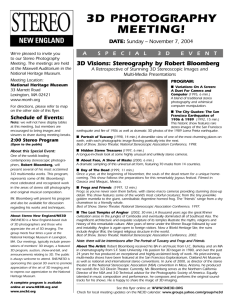

Dials and Channels The Journal of the Radio & Television Museum 2608 Mitchellville Road Vol. 17, No. 3 Bowie, MD 20716-1392 www.radiohistory.org (301) 390-1020 September 2011 Recalling FM Stereo’s Early Years on its 50th Anniversary By Lynn Christian [Lynn Christian is a true radio pioneer in addition to being an RHS Board member. We’re grateful to him for sharing his memories of a watershed moment in radio history.—Editor] FM stereo radio, though initiated in 1961, did not fully impact audiences and advertisers until the mid-1970s. It was my personal pleasure to experience much of this turnover as it happened. What follows is a personal journal recalling some of the events and people who made a difference in first bringing stereo FM radio into the nation’s homes and automobiles. stereo service. (AM stereo appeared years later, but was botched by both the FCC and broadcasters and mostly failed in the marketplace.) From his third edition of A Broadcast Engineering Tutorial for Non-Engineers, former NAB Director of Communications Engineering, Graham Jones, (writing in my kind of language), describes the system: In April 1961 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved a system of FM stereo broadcasting including modifications recommended by the National Stereophonic Radio Committee (NSRC), an engineering test group founded in 1959 by the Electronics Industry Association (EIA) and the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). Two-channel stereo sound, consisting of left and right program channels is used almost universally at analog FM radio and TV broadcast stations. No matter what type of analog broadcast station is involved, all stereo broadcast systems use a method for coding the left and right audio channels that Several of the seventeen systems under consideration utilized both AM and FM signals, but ultimately the FCC authorized stereo employing only FM when, in October 1961, the Commission denied petitions for AM stereo, stating that ―FM was the ideal medium‖ for providing the best possible radio broadcasting As of January 1, 2012, the Radio History Society and The Radio & Television Museum will undergo an official name change and become the National Capital Radio & Television Museum! Dials and Channels September 2011 Page 1 When FM began, elaborate AM-FM consoles were widely advertised, but by the late 1950s, inexpensive plastic table model FM sets like this Granco were gaining in popularity. ensures the stereo signal can be decoded and played by both stereophonic and monophonic receivers. To learn more about this process see the ―History of FM Stereo‖ entry in the Encyclopedia of Radio, Volume 3, edited by Museum Board Chair, Chris Sterling. Beginning as the general manager of America’s first fulltime stereo FM radio station in Houston, Texas (KODA-FM), it has been my pleasure to observe the many benefits this quality aural service has consistently provided listeners over the past 20 years. While recognizing the progress FM radio attained following this FCC decision, I will focus mostly on some memories and observations regarding the economic, programming and audience changes that In 1959 Houston station KODA-FM, Foley’s Department Store, and Sound Equipment, Inc. joined forces to sponsor an “FM-Stereo Spectacular” to attract attention to stereo FM broadcasting. Dials and Channels Consumers who wanted FM at the lowest possible cost could purchase plastic table models like the Granco pictured to the left, but retailers strived to convince consumers to purchase more expensive consoles like the dual-speaker Sylvania model shown here, for which the profit margin was much greater. (Of course the Sylvania would have sounded much better than the $29.95 Granco.) occurred as FM rose to become the country’s dominant radio medium. In Houston, we joined with six other FM station managers in late 1959 to promote purchase of a lowcost FM table model radio as a Christmas gift, which Granco sold for just $29.95, dispelling the theory that only wealthy people could afford to access our unique static-free sound and different programming. The campaign was on the air, on billboard signs and in newspaper ads supported by the local retailers. After KODA-FM initiated stereo FM multiplex radio, we produced a Houston FM-Stereo Spectacular, sponsored by Foley’s Department Store, then the city’s largest retailer, and Sound Equipment, Inc., Houston’s largest hi–fi/stereo component dealer. During the event, at a new downtown hotel, we featured many new stereo FM components, large home entertainment consoles and seminars for do-it- The Radio & Television Museum: A cooperative venture between the City of Bowie and the Radio History Society. September 2011 Page 2 As the demand for stereo hi-fi units mushroomed, companies such as EICO and Heathkit rushed to market kits for FM tuners, multiplex adapters, preamps, and stereo amplifiers. At the Houston FMStereo Spectacular, kit building sessions were offered to the public. yourselfers, instructing how to assemble Heathkit components. The expo was a big success. Additionally, to promote the sale of FM stereo radios, we assisted retailers by presenting daily broadcast periods of stereo demonstration LP album music, often referred to as ―ping-pong music,‖ seven days a week. These recordings gave a strong left/ right channel presence which aided receiver demonstrations. At the Consumer Electronics Industry (CEI) convention in 1967, Audio Times urged CEI members to ―sell radio,‖ and especially ―stereo,‖ because it was, in their words, ―a big dollar sale and was often the biggest contributor to profits‖…even more so than from the sale of color TV sets. With a new Gates stereo studio console, stereo turntables, stereo cassette players and Ampex stereo tape decks at KODA-FM, we began to experiment with producing stereo commercials. Broadcasting, the industry’s leading trade magazine, on June 29, 1963, acknowledged that ―Advertisers Like Stereo‖ in a feature article adding impetus to commercial stereo FM. As I later stated in Michael Keith’s book, Talking Radio: Dials and Channels Before being able to offer FM stereo broadcasts, stations had to make significant capital investments. Here Doug Dodd of Tulsa station KMOD proudly shows off new studio equipment from Gates, Ampex, and Collins. In the early days in Houston and New York all of the independently programmed FM stations worked together promoting FM stereo radios for homes and cars…I consider this phase in its history as Radio‟s renaissance…most of us were not in it for financial reasons; those rewards took a long time to arrive. We just loved the new sound of stereo FM…it was an era, I believe, that had a major role in shaping the values of FM stations today. In this same book, former FCC Chairman Newton Minow added: Stereo FM really exploded in the sixties and seventies. It helped put FM on the map. During the 1960s, however, few commercial FM stereo stations were profitable. Most listeners did not yet own stereo radios, while barely half of the stations utilized stereo transmission and studio equipment. FM radio penetration of American homes across the country in 1961 was around ten percent. Because of this, few advertisers were willing to support their efforts. Most independent FM operators employed fewer than five people and many relied solely on revenue they received from separate background-music services or small retail businesses. Finally, the majority of FM stations on the air 50 years ago simply duplicated the programming of their ―big brother‖ AM station. The September 2011 Page 3 Radio stations advertised heavily in magazines and newspapers when they launched FM stereo broadcasting. This full-page ad from Atlanta’s WSB, which appeared in the July 29, 1963 issue of Broadcasting, is a good example. Dials and Channels September 2011 Page 4 I had the pleasure of managing station KODA-FM in Houston when stereo FM was introduced. Here KODA Program Director Ron Schmidt (right) records an overnight classical music program while announcer Bill Maritin is on the air with a mid-day music program. FM audiences were mostly regarded as ―free bonus listeners‖ for radio advertisers. On November 26, 1961, KODA-FM went on the air in stereo eighteen hours a day. Our small company (owned by a creative Paul Taft) fervently believed, as did I, that FM stereo was a high-quality product that our listeners wanted…or soon would. Our early listeners (we first aired in November 1958 as KHGM—‟The Home of Good Music‖) had said that our high fidelity sound, limited commercials, quality and presentation of music not being aired on AM radio, would keep them with us on FM. Listeners eagerly awaited FM stereo and FM car radios. Helping to build momentum for FM stereo, the recording industry in 1958 introduced stereo longplaying albums, developing America’s growing taste for stereo entertainment. A year later, in order to build momentum for FM broadcasting, to lobby the FCC to end the duplication of AM programming on sister FM stations, and to encourage the development of FM stereo, the National Association of FM Broadcasters (NAFMB) was formed. There were just 26 independent FM broadcasters meeting in Chicago in January 1959. Those of us who attended were later blessed with some excellent leaders during the next decade, including T. Mitchell Hastings of the Concert Network in Boston, Jim Schulke from New York City, and James Gabbert from San Francisco. Dials and Channels Consumers who already owned a monaural FM tuner could purchase a multiplex adapter to capture the stereo sound. (Of course you would need another channel and speaker, too.) During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the leadership was admirably led by Abe Voron of Philadelphia. The NAFMB grew to include over 1000 stations by the late 1960s and became the National Radio Broadcasters Association (NRBA). Eventually peaking at nearly 2000 members, it merged with the NAB in the 1980s. NAFMB/ NRBA’s early efforts in Washington and elsewhere promoting FM stereo built the foundation for its success. But that success did not come easily, as a front page story related in the Wall Street Journal on November 27, 1964: Stereophonic broadcasting has provided a lucrative new service for FM stations. The two-signal system, approved by the FCC in 1961, approximates the „depth‟ quality of actual musical performance. The stereo effect can be heard only by listeners who have stereo receivers. Advertising from phonograph record companies and other makers of high fidelity equipment also shot up since stereo broadcasting began…but more diverse sponsors may be attracted to FM soon. Indeed, this story in the Journal came just six months after I had moved to New York City and put September 2011 Page 5 An ad from New York station WRFM—another example of the promotion of FM stereo. The emphasis is on quality—quality of the sound and of the operatic music that WRFM listeners could tune in. Dials and Channels September 2011 Page 6 the Daily News‟s WPIX-FM on the air. It reflected perfectly the lack of advertising support for FM radio in its early years. We soon discovered that to build audiences we had to give them more than simply long segments of classical music recordings or wall-to-wall background music. Thanks to the recording industry’s interest in promoting stereo, many new recordings were released, which the stations’ music directors could select and play. The remastering of big band albums or singers, light classics, and show tunes began to fill the FM stereo airwaves all over New York. By late 1965, just four years after the FCC stereo decision, WTFM, WRFM, WNCN, WNEW-FM, WABC-FM, WPIXFM and FM’s first full-time stereo rock-and-roll station, WOR-FM, caught New York City radio listener’s ears. You started to hear FM stereo stations everywhere. Listeners wanted to be ―tastemakers‖ and FM stereo became Manhattan’s new ―Happening Place!‖ (as it was promoted in the 1960s). The first seven years of FM stereo, 1962 to 1969, brought FM broadcasters together into local organizations focused primarily on promoting the advantages of FM stereo radio’s unique sound and different formats. Stations worked with local highfidelity, appliance, music, and department stores to cooperatively promote FM stereo receivers and their own stations. This retail awareness of FM stereo was highly important. Indeed, some AM/FM station owners began to separate their own programming before a final edict requiring such a program effort was instituted in the late 1960s. Stations met the requirement using automation. For example, here in the Washington area, WMAL-FM moved from its AM program format to a full-time automated stereo music service conceived by their vice president and general manager, Fred Houwink, as reported in Broadcasting on June 2l, 1965. The entire $16,000 system (about $94,000 in 2010 dollars), was built by station engineers and utilized reel-to-reel and tape cartridge players and twelve turntables. The only manual operation needed was the cueing of records. Besides the FCC approval of the technical standard itself, the biggest game-changing event for FM stereo was, of course, the FCC requirement to separate programs on co-owned AM and FM stations, As Chris Sterling and Michael Keith put it in their 2008 history of FM, Sounds of Change: ―… as (FCC) rulemaking begun in 1961, formally Dials and Channels KXLS in Oklahoma City was another station that adopted FM stereo broadcasting when it was a new technology. proposed in 1963, and adopted in 1964, (to be effective the next year) was finally in effect only at the start of 1968….‖ This critical rule basically required that in all United States markets with a population of 100,000 or more (about 125 of them at that time) AM/FM station operators would be required to provide separate programming for each station, half of every broadcast day. Sterling and Keith concluded: “It is sufficient to note that the FCC‟s forced creation of a separate FM program „voice‟ would prove to be a vital factor in FM‟s eventual dominance over AM.” FM’s dominance became so pronounced after 1980 Washington, D.C. station WMAL-FM began automated stereo broadcasting in May 1965. Its own engineers built the equipment shown here that enabled the station to do so. September 2011 Page 7 that eventually much of AM radio abandoned music programming for talk, news, or sports radio, or in some cases, religious or ethnic formats. For nearly twenty years, FM stations retained their policies of limited talk and commercials, along with quality music programming. Once FM stereo radio became the listeners’ first choice, and FCC ownership rules and regulations were radically modified, many traditional aspects of early commercial FM programming ended. This has been primarily due to the addition of greater competition, changing music tastes of America’s younger audiences, and the pressures of seeking high station ratings. In 2011, the most successful radio station in the country is WTOP, Washington, D.C.’s allnews station. No longer on AM, it is now heard on three FM dial locations in the national capital area. Today the radio industry is witnessing more moves from AM and FM technology due to the advent of FM’s new digital services on the same channels (i.e., HD radio), digital streaming over the Internet, cell phone radio chips (just beginning), digital satellite radio, and other methods of worldwide distribution. The instant widespread access to radio on these new personal devices is especially relevant given the importance of receiving instant news, weather and traffic information. Emergency messages, as recently witnessed during the Spring 2011 rash of horrific tornadoes and for ―Amber Alerts‖ (conceived by a small market radio station operator in California), are vitally needed by today’s 21st-century listeners. The evolution continues for FM stereo, as it begins its second half century. For me, FM stereo radio’s introduction in the 1960s was an exceptional professional experience. While FM, our foremost aural medium, is presently engaged in another transition, this time to digital technology, just remember to ―stay tuned… radio is here to stay!‖ ■ The Editor’s Introduction to FM Stereo Lynn Christian’s article brought back memories for me. I recall well, how, when I began college in southern California in 1959, several of my dorm friends acquired hi-fi systems in which one channel of the stereo was received on AM and the other on FM. Prior to the availability of multiplex FM stereo, companies offered AM-FM tuners designed to provide that kind of two-band stereo listening. It was better than monaural radio, but not nearly as good as what was to become available shortly thereafter when stereo multiplexing began. About 1964 I purchased and built my first hi-fi stereo system. It included a Dynakit FM tuner, preamp, and amplifier, an AR turntable, and JBL speakers, all housed in an eight-foot long walnut Barzilay cabinet kit. I recall vividly how awed I was when I finished putting it together, turned it on, and tuned in classical music station KCBH from Beverly Hills. The sound quality was so much better than our old Zenith AM clock radio I was blown away. I could not believe my ears. Announcer Hamilton Williams and the orchestra sounded as though they were right in our living room. Today we take high-quality sound for granted, but I continue to be thankful to those who developed FM stereo half a century ago. For more of the history of FM radio, check out the book in our gift shop co-authored by Museum Board President Christopher Sterling and Michael Keith: Sounds of Change: A History of FM Broadcasting in America. And, for Chris Sterling’s recollections about early FM stereo, see page 11. - Brian Belanger Dynakit’s FM-3 stereo FM tuner provided high quality music delivered by FM stereo. Dials and Channels September 2011 Here I am putting together the cabinet for my stereo hi-fi system. Page 8 We Interrupt this Newsletter to Bring You a Special Bulletin: The Museum Has Hired Its First Employee! By Brian Belanger T he Radio and Television Museum has hired its first employee. Laurie Baty began work (part time) at the end of May and has already proved to be a terrific addition. Her resume is impressive. Just to cite three jobs she has held: Senior Director of Museum Programs at the National Law Enforcement Officers Museum Deputy Director, Division of Collections, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Chief, Museum Services Branch, Department of the Interior What is more, Laurie is cheerful and fun to work with. In her first few weeks on the job, she has dealt with problems with the Museum’s databases for objects, library materials, and membership. She has renewed all outstanding loans, and she has begun a complete inventory of the collections—something that has never been done before, but definitely needs doing. Not only that, but Laurie recruited an intern—Joy Veenstra—to help speed up taking the inventory. Setting up the paperwork for a new employee kept Treasurer David Green busy, but he has figured out and implemented all that needs to be done to comply with Federal and State employment regulations. We are developing a strategy to approach foundations and corporations, but all of us members also need to help. I plan to increase my level of support for the museum and I urge all my fellow members to consider moving up to the next level of support the next time you renew your membership. ■ What does this mean to Museum members? It means the museum is climbing to the next level of professsionalism. For long-term success, the Museum must have paid professional staff. The Museum will always rely on volunteers to a considerable extent, but to ensure viability, it is not appropriate to rely exclusively on volunteers as we have done up to now. The Board concluded that the Museum has sufficient assets to take this important step at this time, but there is risk associated with taking it. For the Museum to continue to grow, cash flow must be increased. Laurie Baty will help us with that effort. Dials and Channels Joy Veenstra, the intern recruited by Laurie Baty. Thanks to Joy’s help, the inventory is proceeding much more rapidly. September 2011 Page 9 Museum Volunteer Spotlight: Tony Young [This is part of a continuing series about Museum volunteers—people who are essential to keeping the Museum running.] T ony Young grew up in Massachusetts, working part time at an ice cream stand, where he said he dished up thousands of scoops of delicious flavors, resisting the temptation to sample them too often. He made all of the ice cream! Tony chose to serve his country by joining the Navy. He was stationed in a number of different far-flung locations, including Guam, as an intercept radio operator. To do this job, Tony had to train diligently to acquire the special skill of accurately receiving high-speed encrypted Morse code messages that would later be decoded by the intelligence community. He was a fast learner, and even today, he can send and receive Morse code at lightning speeds. an RHS Board member as well as Museum member -ship chair until recently, and he is also in charge of the Museum’s tube program. Almost every Wednesday Tony can be found (often with Oscar Ramsey) at the tube warehouse in Davidsonville, Maryland, sorting, testing, and cataloguing tubes. Tube sales are an important element of the Museum’s revenue stream. Tony also obtained the use of three buildings for the use of the Museum and the Mid-Atlantic Antique Radio Club at the Davidsonville Family Recreation Center. Invariably cheerful and good humored, Tony is the sort of guy who is always willing to help when something unexpected comes up at the Museum, which happens more often than we might like. Because he lives close by, he is willing to stop in on short notice. Without loyal volunteers like Tony, the Museum simply could not function. ■ When he was discharged from the Navy, Tony was hired by IBM, and quickly became an electric typewriter expert, making valuable suggestions to the company for improving their designs and servicing procedures. He served as an instructor to teach new IBM employees about those famous Selectric typewriters. When he retired from IBM he was able to devote more time to his ham radio hobby and the Anne Arundel Amateur Radio Club. (Tony’s call is WA3YLO.) For a long time he managed his ―Widow’s Assistance Program,‖ helping spouses of deceased hams dispose of equipment. Tony is dedicated to community service, having served on an advisory board dealing with issues of foster children. He is also a regular volunteer at his church, with the Bowie Senior Center, and with the Knights of Columbus. Tony joined our crew before the museum opened its doors, and ever since he has been one of our hardest working volunteers. For many years he has been the person in charge of the museum virtually every Saturday. In addition, he is usually at the museum for part of the day most Fridays, and is often a docent for special tours during the week. Tony was Dials and Channels Tony Young, standing near the entrance to the Museum, showing off an impressive Western Electric transmitting tube from the Museum’s collection. September 2011 Page 10 More Recollections of Early FM Stereo By Christopher Sterling Special Lecture at the Museum Saturday, October 15, 2 p.m. I started as a student announcer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison's WHA in September 1961, just after I'd entered as a freshman (my first semester tuition bill was $110!). For a year or so, the station had broadcast two-station stereo, with the AM daytime only station providing one channel, and WHA-FM providing the other. Announcing when the transition from monaural to stereo was to begin was a bit tricky. We had a standard script to explain what we were doing and why—and what the listener would gain by continuing to listen. And, of course, we had to tell listeners that they needed to use two radios (one AM and one FM) in the same room, and roughly how to set them up to get the right effect. Armstrong: The Man Behind FM Radio Then, if I remember correctly (let's face it, this was a half century ago!), we would "bring in" the AM channel followed by the FM for a classical music broadcast. Of course the two channels didn't really balance well given the poor signal response of an AM channel compared to FM. But the sensation of two different signals was astounding when you heard it for the first time. The experiment was also weakened by the fact that so few households owned an FM receiver in Madison in 1961. Estimates hovered around 20 percent. Perhaps the two-station broadcasts helped to sell a few more. After the FCC approved multiplex FM stereo, as described well by Lynn Christian in this issue, WHA fairly quickly gave up on the two-station approach and switched over to FM stereo for its heavily classical music programming. And slowly the number of FM receivers grew as well, though at first few were built to carry the stereo signal. Many of the earliest models had separate channels, but being all of six or so inches apart, you practically had to sit on top of the radio to get any stereo effect. While I never had the knowledge or ability to build my own rig (such as Brian Belanger describes elsewhere in this issue), I finally did get a combo radio phonograph with separate speakers that could be placed several feet apart. That was the real beginning of FM stereo enjoyment for me. ■ Dials and Channels Edwin Howard Armstrong (1890-1954) was one of the most important figures in American radio, with three radio innovations to his credit before he began to focus on FM radio as a way to avoid the static that plagues AM. To the surprise of many, he succeeded, creating a new system of radio transmission in the early 1930s—and then spending the remaining two decades of his life fighting for its success. His is a story of perseverance and, in the end, tragedy. Yet nearly six decades after his death, we still enjoy the fruits of his efforts. Our distinguished speaker is Dr. Christopher Sterling, who chairs the museum's board. He has been at George Washington University for three decades. Author or editor of nearly 25 books (one of which, Sounds of Change, is a history of FM radio, copies of which are available at the museum gift shop), he was recently named an associate dean of GW's Columbian College of Arts and Sciences. Not only is Chris the current board chair, he also regularly serves as a docent at the museum and is a key person in designing and implementing the exhibits the museum has at the George Washington University. While you are at the museum to hear this lecture, you can view a relatively new exhibit about FM radio. On display are two pre-WWII radios with the old FM band. Originally the FM band was in a different location in the fre-quency spectrum—42 to 50 MHz. Today, of course, the FM band is assigned to the 88 to 108 MHz range. When the band reallocation occur-red in 1945, it meant that anyone who had purchased an FM radio prior to the war suddenly had an obsolete device. (It is some-what analogous to our having to deal with the recent transition from analog broadcast TV to digital TV.) The FM exhibit at the museum summarizes how FM came to be and explains the difference between AM and FM broadcasting. ■ September 2011 Page 11 Donations: April to July 2011 Arcadia Publishing Charleston, S.C. Book – Chattanooga radio history Elsie DeWall Derwood, Md. Zenith Model G672BT Susie Bachtel Arlington, Va. Two boxes of radio service literature Gene Duman Reston, Va. Book and magazines Daniel Barbieri Olney, Md. National 183D communications receiver, Heathkit CR-1 crystal set, Vibroplex speed key Paul Farmer Washington, Va. Regency TR-1 transistor radio (This is the world’s first transistor radio model offered to the public!) Michael Beaghen Alexandria, Va. Book – Tube [history of television] Alan Feinstein Columbia, Md. Five Heathkit items, other test equipment John Bruce Frederick, Md. Atwater Kent 60 Michael Canavan Bowie, Md. Panasonic VCR Lynn Christian Ashburn, Va. Book: Broadcast Engineering Tutorial Steven Edward Clark Bowie, Md. Sony color TV and antenna Joe Colick Clinton, Md. Airline GEN 1937A clock radio, Westinghouse H-871N6 radio, both fully restored Lee Craft Alexandria, Va. Radio parts, more than 100 radio & TV tubes Sarah Crim Bowie, Md. Book: International Code of Signals John Gillan Parkville, Md. Book: Radio Education Pioneering in the Mid West Albert Gimbalvo Fairfax, Va. Box of vacuum tubes Sidney Greenspan Chevy Chase, Md. RCA 170T TV set, many radio books, other items Thomas Harryman Baltimore, Md. Silvertone Medalist transistor radio Joe Haupt Ellicott City, Md. Truetone DC 1454, Sentinel table model Elizabeth Kipps Rochelle, Va. GE P-720-B, American Bosch 28, parts cabinet Robert LaFollette Sykesville, Md. Sony portable TV David Lavender Potomac, Md. ~25 used vacuum tubes David League Richmond, Va. Emerson 605 radio, Emerson 606 TV, Zenith Trans-Oceanic, Minerva table model, many other radios Barbara McBride Bowie, Md. Ham equipment, books, parts Barbara Newbury Gaithersburg, Md. Radiola 80, old tubes Janet Sanford Linthicum, Md. Penton wire recorder and wire spools, GE transistor radio Gilbert Saunders Bowie, Md. Grundig Satellit 800, Sony active antenna Gerald Schneider Kensington, Md. Emud model T-7 Mark Hilliard Allentown, Pa. RCA Model 303 Braille radio Perry Sennewald Charlottesville, Va. Hotel Radio Corp. Model 6A coin-operated chairside radio Rowland Johnson Reston, Va. Reference books Richard Short Bowie, Md. Philco 91X console Cathryn Davis Herndon, Va. Harmon Kardon Citation amplifier, test equipment, parts, tubes, books Dials and Channels September 2011 Page 12 Michael Simons National Electronics Museum Linthicum, Md. Three radio tubes Robert Snow Bowie, Md. Channel 4/NBC items Jack Thompson Edgewater, Md. 1936 Monarch table model, Conar tube tester, Wireless Cyclopedia reprint Debbie Wheeler Derwood, Md. Philco 42-390X console David Sproul (WMAL) Washington, D.C. WMAL station material (rate card, log, etc.) Nancy Wilson Petaluma, Ca. 1932 radio clipping - NY Times Christopher Sterling Annandale, Va. 28 radio and TV books Robert Wilson Hyattsville, Md. Audio amp and FM tuner Peter Wittenberg Annapolis, Md. ~7,000 radio tubes Lynn Wright Silver Spring, Md. Sony boombox & VCR, Pioneer SX-1010 stereo receiver, Atwater Kent Model 84, Teac Dolby unit, other items Tony Young Bowie, Md. Shure SW109 microphone ■ Our Generous Museum Members W e are truly grateful to Museum members who maintain their memberships at levels above the basic level. Such support is critical to the Museum’s success. Whatever your current level, when your membership renewal comes up, please consider renewing at a higher level. (And, if your membership is at a level higher than basic, and if you prefer to remain anonymous, please make that fact known to us and we will not list your name here.) Patron Level ($250/year and above) Anonymous Brian Belanger John Berresford Jim Bohannon Lynn Christian Robert Coren C. L. Gephart Rowland Johnson William McMahon James O’Neal Roy Shapiro Ludwell Sibley Dials and Channels Benefactor ($100 to $249/year) Supporters (continued) Michael Beaghen Barry Cheslock Noel Elliott Paul Farmer Stan Fetter John Foell Donald Gibson David Goodling Bill Goodwin Greg Hunolt David & Joanne Kelleher Joe Koester Paul Lewis Edward Lyon, III Byron Roscoe Charles Schenck Gerald Schneider David Simon Christopher Sterling Mary Ellen Stroupe John G. Tyner II Ed Walker Davis Wilson Adrian Dales Sam Dedonatis Robert Duckman Michael Edelstein Michael G. Freedman Robert Gardner Charles H. Grant David Green Kurt & June Heinz Paul Klein David League Terry Lohman Dick Maio Steve Malley John McKellar Ken Mellgren Maurice Moore John Okolowicz John Robinson Don Ross Robert Ross Charles Sakran David Schaefer Neal Schiff Merrick Shawe Russ Shipley Michael Simons William J. Steele Sara Stephens Susan Stolov Cal Trowbridge Robert Wirsing ■ Supporters ($50 to $99/year) John Beers Camille Bohannon Ray Brubacher W. Michael Byrnes David Churchill September 2011 Page 13 Radio and Television Pioneers Museum Website Progress Sidney Harman died in April at age 92. He was a key individual in the development of high fidelity. Harman began working for David Bogen & Co. in the 1930s. (Bogen made PA systems and amplifiers.) He and a Bogen colleague, Bernard Kardon, left Bogen in 1953 to found Harman Kardon—a company that was a leader in the early days of high fidelity systems, and later expanded into Harman International, which today provides a wide variety of modern electronic gadgets, and includes brands such as JBL, Mark Levinson and Infinity. Harman Industries has 11,000 employees and $3.5 billion an annual sales. Several members have asked about a membersonly page on the Museum website—and it's coming! By late September, it should be up and running with lots of special features available only to paid-up members, including a complete back file of Dials and Channels, and many other radio-TV related documents. When the page is ready, an email will go out to members telling you how to gain access. (We had expected to have this feature implemented much sooner.) Once it is in place, it will constitute yet another important reason for maintaining your Museum membership. ■ Harman served as Undersecretary of Commerce in the Carter Administration. He purchased Newsweek magazine shortly before he died. His wife, Jane Harman, was a member of Congress. He contributed large sums to Washington area non-profits, such as The Washington Ballet and the Shakespeare Theater Company. Bob Banner is another pioneer who died this year. RHS member Dick Jamison calls Banner ―one of the true shapers of commercial television (for good or ill).‖ Jamison was a page boy at NBC in Chicago in the early 1950s and saw Banner’s work first hand on shows such as Kukla Fran and Ollie and Garroway at Large, adding that ―his name was spoken in terms of awe by TV staffers even then.‖ Banner began working in television in 1948 and became a storied executive producer. His show Candid Camera was one of the most popular in its day. Other shows of his featured stars such as Perry Como and Gary Moore. For CBS he produced Omnibus, with Alistair Cooke. His company, Bob Banner Associates, became one of the longest-running independent production companies in television and pioneered the idea of selling syndicated shows to cable networks. In 1958 he won an Emmy for directing The Dinah Shore Chevy Show. (Dinah Shore singing, ―See the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet‖ is an iconic moment in early television.) In one of those shows, Banner proposed to have Dinah and Nat King Cole sing a duet. NBC officials objected to the proposal, fearing that it would antagonize southern viewers. Banner quit in protest but was rehired in a week. ■ Dials and Channels RHS Vision and Mission Statements Vision: The Radio History Society seeks to foster an understanding of the impact of radio-television technology and the power of broadcasting to shape the world, while encouraging the public to pursue an understanding of this history to mold the future. Mission: The Radio-Television Museum, governed by the Radio History Society, seeks to educate the public about the history and impact of radio and television technology and broadcasting, though the Society’s efforts to collect, preserve, and interpret radio and television artifacts, programming, and publications, starting with the dawn of radio. ■ NRI’s Fascinating History In 1999 the Museum inherited the archives of the National Radio Institute (NRI) when NRI closed its doors. Washington, D.C.-based NRI was the leading provider of home-study courses in radio and television for most of the 20th century. Recently the Museum videotaped an oral history interview with Jack Thompson, who headed NRI for many years. A DVD of the interview will be available soon in the Museum library. Museum Director Brian Belanger is working on a comprehensive history of NRI. The ad on page 15 appeared in the July 1956 issue of RadioElectronics magazine, and is typical of the highly effective marketing by NRI. ■ September 2011 Page 14 Dials and Channels September 2011 Page 15 New Board Member: Lindsey Baker The Museum’s Board of Directors has been looking for additional Board members who could bring helpful skills to the job. The Board recently selected Lindsey Baker to fill a vacant Board position. Lindsey is a graduate of Goucher College, with a B.A. in History, and an M.A. in History and Museum Studies from the University of Delaware. She is the Executive Director of the Laurel Historical Society (since 2008), and in that role handles a wide variety of tasks, including museum operations, fundraising, supervising volunteers, etc. In short—the same kinds of challenges our Museum faces. She is the Secretary of the Maryland Association of History Museums and serves on the Conference Committee of the Small Museum Association. Her experience in running a very successful small museum makes her particularly well qualified to provide helpful advice to our Museum on multiple topics. ■ Acknowledgement The Museum thanks the Shiers Memorial Fund for its help in underwriting the cost of printing and mailing this journal, as well as improving the Museum’s website. RHS Officers and Directors President Chris Sterling (2014) 4507 Airlie Way Annandale, VA 22003 (703) 256-9304 chsems@verizon.net Vice President Peter Eldridge (2012) 6641 Wakefield Dr. #205 Alexandria, VA 22307 (703) 765-1569 peter.eldridge@ed.gov Treasurer David Green (2012) 413 Twinbrook Parkway Rockville, MD 20851 301-545-1127 djgmcg@hotmail.com Executive Director and Newsletter Editor Brian Belanger (2013) 115 Grand Champion Drive Rockville, MD 20850 (301) 258-0708 radiobelanger@comcast.net Directors Lindsey Baker (2013) 301-725-7975 Lynn Christian (2014) (703) 723-7356 Paul Courson (2014) (202) 898-7653 Michael Freedman (2014) (703) 838-0013 William Goodwin (2013) (410) 535-2952 Charles Grant (2012) (301) 871-0540 Dials and Channels September 2011 Directors (continued) Michael Henry (2013) (301) 474-5709 Caryn Mathes (2013) (202) 885-1214 Bill McMahon (2013) (304) 535-1610 Ken Mellgren (2012) (301) 929-1062 Pamela O’Brien (2012) (301) 486-1402 James O’Neal (2014) (703) 852-4632 Michael Simons (2014) (301) 698-8230 Ed Walker (2012) (301) 229-7060 Page 16