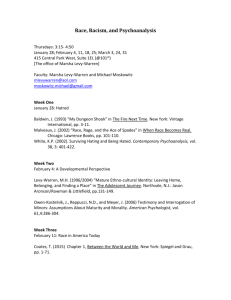

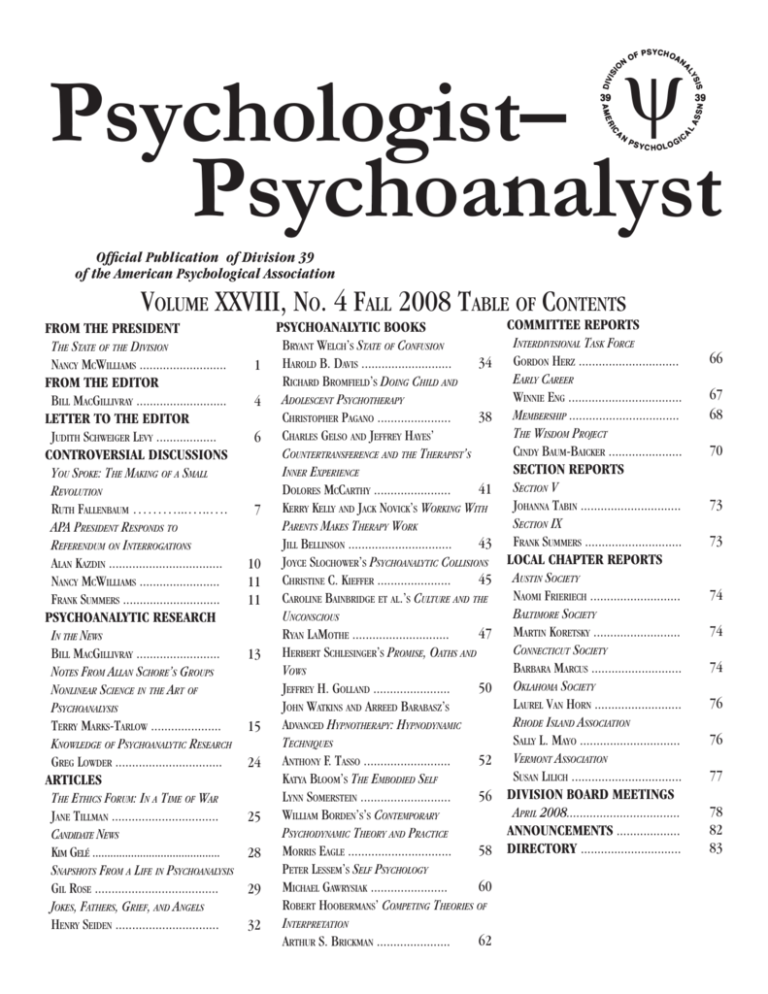

Fall - APA Divisions

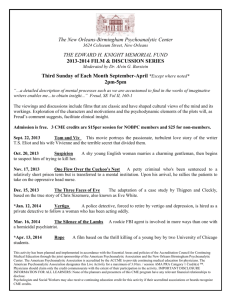

advertisement