Policy Debate Manual from Emory University

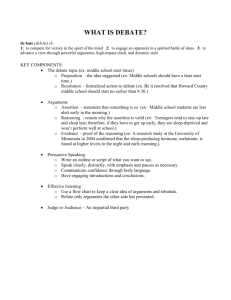

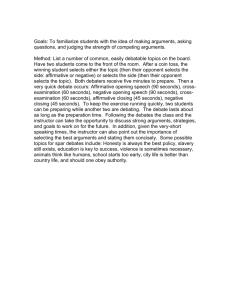

advertisement