Environmental Ethics and Species: To be or not to be?

advertisement

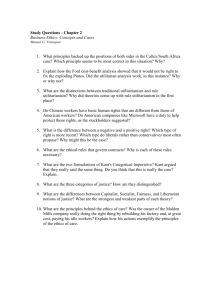

Environmental Ethics and Species: To be or not to be? Darren L. Weber c 1993 Copyright Written in November, 1993 Philosophy: Environmental Ethics Environmental Ethics and Species 1 1 Environmental Ethics and Species: To be or not to be? The present rate of the extinction of species, due to human activity, is an environmental catastrophe that is unparalleled in the history of life on earth. The morality of human interactions with other species has been one of use and abuse. However, ethical theories of human interaction can be extended to the interactions of people with other sentient species. This extension is problematic, however. A sound basis for the morality of the interactions of humanity and other species can only be found in an holistic approach, such as that of Aldo Leopold’s “Land Ethic”. 2 Species Extinction Species have never disappeared as quickly as they are doing now.1 During the mass extinction of the late Cretaceous period, which included the extinction of the dinosaurs, a species became extinct every 1,000 years. Humanity arrived about 50,000 years ago and began to extinguish species by simple hunting methods, particularly the use of fire. Between 1600–1900, a period of industrialization and the development of sophisticated weapons, humanity accounted for the extinction of a species every four years. Since 1900, humanity has extinguished 75 known species and many unknown species, at a rate of one species every year. During the last quarter of the 20th century, humanity could account for the extinction of one million species, at a rate of 100 species every day. The rate of species extinction is diminishing the capacity of evolution to generate life. The evolution of a species occurs over thousands or millions of years and depends on a diversity of genetic combinations from which successful mutations can emerge.2 Species are disappearing faster than they can be replaced by natural selection or genetic engineering. Furthermore, the preservation of the frozen genomes of species cannot replace the complex contingencies of the habitats that define and sustain a species. The present rate of the extinction of species and their habitats will impoverish life on earth for millions of years. 3 Preservation of Species Why preserve species? Furthermore, what species should be preserved? Answers to these questions vary and depend on variations in the substance of morality, whether it is utilitarian or deontological or anthropocentric or holistic. 3.1 Human Interests in Species Preservation Morality is traditionally concerned with human welfare, particularly the propriety of human interactions. However, human beings interact with other species. It is not surprising, therefore, that morality has been concerned with the propriety of human interactions with other species. Traditionally, this concern has focused on the satisfaction of human needs and wants as these relate to other species. Species that satisfy human needs should be preserved, else human welfare is disturbed. Furthermore, those species that harm human beings (e.g., viruses, bacteria, various poisonous plants, and various animals such as snakes and tigers) should be at least “kept out of harm’s way”, if not eradicated. From this anthropocentric perspective, the extinction of the small-pox virus, for instance, was one of the greatest interventions of modern medicine and hopes exist for a similar eradication of many other viral or bacterial infections (e.g., HIV). Anthropocentric ethics deny that animals that can suffer have interests that people should respect. William Baxter, for instance, raises the question of whether penguins should be protected from the agricultural use of DDT, 1 The estimates of species extinction in this paper come from Norman Myers, “The Sinking Arc”, in D. Van De Veer (Ed), People, Penguins, and Plastic Trees, Wadsworth, 1986, pp. 111–112 and 116–119. 2 Ibid, pp. 116–119. Environmental Ethics and Species 2 which would otherwise kill them. He suggests that what should be done about the pollution of penguins depends only on how possible solutions affect people. He states, Damage to penguins, or sugar pines, or geological marvels is, without more, simply irrelevant. One must go further . . . and say: Penguins are important because people enjoy seeing them walk about rocks; and furthermore, the well-being of people would be less impaired by halting use of DDT than by giving up penguins. . . . I have no interest in preserving penguins for their own sake.3 Baxter believes that we have no moral obligations to other species, per se, since they have no interests that should be respected by people. Baxter proposes that there are no normative implications of “the state of nature” and that people should pollute the environment just as much as they please. As he put it, I reject the proposition that we ought to respect the “balance of nature” or to “preserve the environment” unless the reason for doing so . . . the benefit of man. From the fact that there is no normative definition of the natural state, it follows that there is no normative definition of clean air or pure water hence no definition of polluted air or of pollution except by reference to the needs of man. The “right” composition of the atmosphere is one which has some dust in it and some lead in it and some hydrogen sulphide in it just those amounts that attend a sensibly organized society thoughtfully and knowledgeably pursuing the greatest possible satisfaction for its human members.4 For Baxter, people should enjoy wilderness areas and clean air, water, and soil, just so long as they want those satisfactions as much as they want others that might require the pollution of wilderness, etc. He states, . . . the costs of controlling pollution are best expressed in terms of the other goods we will have to give up to do the job. . . . Badly as we need more housing, more medical care, and more can openers, and more symphony orchestras, we could do with somewhat less of them, in my judgement at least, in exchange for somewhat cleaner air and rivers.5 Thus, for Baxter, the resolution of environmental problems is a choice or cost/benefit analysis that people should make so that solutions maximize human satisfaction. An anthropocentric morality is capable of some protection of species. If people are cruel or inhumane to specimens of other species, they may develop attitudes and habits that predispose them to inhumane relations with people (which is the moral justification of the R.S.P.C.A). The problem with this humane morality is that it still remains possible to destroy other species providing that their destruction has no adverse impact on human relations. Thus, the HIV virus, for instance, feels no cruelty and harms human relations. 3.2 Animal Liberation or Animal Rights? Peter Singer argues that utilitarianism should encompass all sentient animals.6 Utilitarianism proposes that the good is the experience of pleasure and the absence of pain.7 Applied to social relations, utilitarianism asserts that actions should provide “the greatest good for the greatest number”. Utilitarian ethics were restricted to human beings because it was believed that animals have no feelings. The Cartesian dualism of mind and body associated emotions with the soul that is detached from the body. Animals, unlike people, have no soul and therefore 3 William Baxter, “People or Penguins: The Case for Optimal Pollution”, in D. Van De Veer (Ed), People, Penguins, and Plastic Trees, Wadsworth, 1986, p. 215. 4 Ibid, p. 216. 5 Ibid, p. 217. 6 Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (2nd ed), Thorsons, 1991. 7 There are two forms of utilitarianism: hedonistic utilitarianism and preference utilitarianism. Preference utilitarianism proposes that the good is the satisfaction of prudent desires. However, it is hedonistic utilitarianism that is most applicable to animal welfare, although I suspect preference utilitarianism may be also. There is no need, or room here, to distinguish between act and rule utilitarianism. Environmental Ethics and Species 3 are unemotional. However, a natural understanding of human origins reveals that human sensation, emotion, perception, memory, and thought are functions of a nervous system that remains similar, in many respects, to the nervous system of other animals. Other animals are sensible and feel pleasure and pain. Thus, Singer argues that they too should be included in the utilitarian calculation of the greatest good for the greatest number. A problem with utilitarian ethics is that the principle of the greatest good for the greatest number could entail that some species are disadvantaged or actively exterminated. Firstly, the utilitarian calculus of the greatest good for the greatest number is very difficult when it is restricted to humanity. The present satisfaction of a portion of humanity, let alone all of humanity, is very difficult to evaluate and the different degrees of satisfaction to be had by various people from various sources of satisfaction is very difficult to predict, so the determination of the greatest good for the greatest number after the distribution of limited resources is very, very difficult to evaluate. As applied to all sentient species, it is virtually impossible to evaluate, since it is very difficult to know the feelings of sentient animals other than people. Secondly, utilitarianism can lead to significant inequalities in the distribution of limited resources. For example, among a group of people with 50 units of satisfaction there could be a small group with about 80 units of satisfaction and another larger group with about 40 units of satisfaction, since the small group have exclusive control of some equipment. According to utilitarianism, another 10 units of satisfaction should be distributed to the small group when it can use its equipment to transform 10 units of simple satisfaction into 20 units of added value satisfaction. Assuming that it is possible to know the feelings of sentient animals, a sentient species (e.g., a predator) that inflicts pain on another sentient species should be disadvantaged or extinguished when the satisfaction of that species is less than the satisfaction of the species that suffer pain. Thus, although the utilitarian principle may apply to all sentient species, the difficulties of utilitarianism are insurmountable or the inequalities implied by utilitarianism are likely to promote the extinction of species. Tom Regan argues that deontological ethics should be applied to sentient creatures.8 Kant argued that moral principles should be applied to all people who are aware of right actions and able to understand rational principles of action that should be applied universally and unconditionally. Kant believed that all moral agents should be considered as ends in themselves, with their own purposes to fulfill, rather than means to the satisfaction of others. For example, the principle of treating all people as ends in themselves would prevent slavery, even when slavery would provide for the greatest good for the greatest number. Regan extends the arguments of Kant to encompass all species with awareness of their actions. He argues that just as people have a right to be respected as ends in themselves, so too animals capable of awareness of their actions deserve to be respected as ends in themselves. Thus, animals should not be used in medical experiments, even when the utility of their use is greater than the utility of experiments on people. Although many sentient animals may not have the capacity to understand rational principles of action or their universal, unconditional application, Regan argues that they have a sense of their being and the fulfilment of their purposes that should be respected for the integrated consciousness that it is. An important problem with the rights view of Regan and the utilitarianism of Singer is their failure to recognize the unconditional value of the purpose of actions and the significance of insentient species. Sentient species are alive only because there are many more insentient species alive too. Insentient species are elaborate formations of organic molecules that have a purpose to their functions that is no less important than the purposes of sentient species because insentient species are unaware of their actions or their purposes. Sentient species may be as unaware of the purposes of their actions as any insentient species. The capability to feel pleasure and pain is not necessarily any more sophisticated than the capability of an insentient species to perform a reflex action. The appeal to pleasure and pain as a motivation for action is no more sophisticated than an appeal to reflexes. What is needed is an appreciation of the intrinsic value of purpose, which a species may or may not be aware of. The development of awareness of action and the awareness of the purpose of action is a sophistication of the evolutionary tendency to fulfil purposes, but purposes are no more or no less important because a species is aware of them. Furthermore, the integration of the purposes of species with the purposes of other species is a valuable attribute of evolution and a foundation of the origin of species. An unconditional appreciation of the purposes of species should be associated with an appreciation of the creativity of evolution. 8 Tom Reagan, The Case for Animal Rights, Routledge, 1988. Environmental Ethics and Species 3.3 4 Holism An holistic environmental ethics begins with earnest in the writings of Aldo Leopold. For him, A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.9 Leopold realized the ethical implications of ecology, the science of biological communities or ecosystems. His thought was provoked by a sensitivity to the American mountain lion that was hunted almost to extinction. When the mountain lion was no longer eating deer, the deer population exploded and over-grazed its habitat, disrupting the balance in the well-being of various species of plants and animals there. An holistic environmental ethics acknowledges value in the integration of each species with its habitat and its relations with other species. Each species has a particular pattern of interaction with its environment that fulfils its purposes, whether or not it is aware of them. Furthermore, the dynamic interaction of a species with its environment is a process that forms and transforms the constitution of a species and its environment. The fulfilment of a species is valuable for the realization of life that it is. Furthermore, the reproduction of a species and the transformation of a species is a valuable creation of the potential fulfilment of life. The process of evolution itself is an inherently valuable creation of living potentials. This is not to deny that extinction occurs or should occur. Rather, it is an appreciation of the formation and transformation, generation and degeneration, of species. That a species becomes extinct does not necessarily mean that its genetic characteristics are lost forever. Under normal circumstances the extinction of a species involves the transformation of that species into another species, if not many more species. The devastating impact of humanity, however, is a catastrophe that life on earth will take millions of years to overcome. Human interference is not merely provoking the transformation of species, it is irrevocably eradicating beautiful forms of life. An holistic environmental ethic requires respect for the inherent value and integrity of the interactions of species and the evolution of species that occurs as dynamic interactions of species form and transform species and their habitats. The holistic view implies complex or controversial conclusions about the preservation of species. It acknowledges the value of sentient or insentient species and their interactions, but it does not prescribe preservation of species, per se. Rather, the preservation of species is merely necessary to stabilize the diminution in the capacity of evolution to generate species from the decreasing array of species that exist at present. It is difficult to say that the small-pox virus or a sentient animal should be preserved or extinguished, for it depends on the relationship of these species to the “integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community”. Lawrence Johnson, for instance, argues that ecosystems and the biosphere have significant interests that should be respected, against which the extinction or preservation of a species should be evaluated.10 Furthermore, he argues that within the biotic community all species, even inanimate materials, are valuable, but there are variations in the value of species. Thus, for instance, a small-pox virus would be less valuable that a human being. So, if push comes to shove, the small-pox virus would go in preference to the human being. However, the relative value of a species is not easily identified with the characteristics of a species in isolation from its habitat and the ecosystem to which it belongs. Rather, the relative value of a species should be evaluated with respect to its constitution and its patterns of interaction with an ecosystem or the biosphere. Thus, from an holistic perspective, the value of simple organisms that sustain a large variety of species in a complex food chain may be more valuable than a more complex organism that is effectively a parasite in an ecosystem or the biosphere. Considering the devastation of ecosystems that have been ravaged by humanity, the small-pox virus or the HIV virus may be valuable parasites that ravage an even larger parasite, human beings. 9 Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, Oxford University Press, 1949. For an extensive discussion of the philosophy of Leopold’s environmental ethics, see J. Baird Callicott, In Defense of the Land Ethic, State University of N.Y. Press, 1989. 10 Lawrence Johnson, A Morally Deep World, Cambridge, 1991. Environmental Ethics and Species 4 5 Conclusion The preservation of species should not be a concern for species, per se. Rather, the preservation of species should be a concern for the integrity of evolution. The maintenance and integrity of the interactions of species is the foundation for the evolution of species. Human interference in nature has diminished the genetic diversity of earth and disrupted the integrity of evolution. An holistic environmental ethics should consist in the acknowledgment of the inherent value of the purposes of species whether they are sentient or not. Furthermore, it should acknowledge the inherent value of the creativity of evolution or the dynamics of the interactions of various species. What is truly important is that the integration of species should be valued and that the interactions of species should be respected. The formation and transformation of species is the creativity of nature that is threatened by humanity and that requires redress. Humanity should recognize that the preservation of frozen genetic material is meaningless. Species are nothing in isolation, the evolution of species is at stake. 5 Bibliography Baxter W., “People or Penguins: The Case for Optimal Pollution”, in D. Van De Veer (ed), People, Penguins, and Plastic Trees: Basic Issues in Environmental Ethics, Wadsworth, 1986, pp. 214–218. Callicott J.B., In Defense of the Land Ethic, State University of N.Y. Press, 1989. Johnson L., A Morally Deep World, Cambridge, 1991. Leopold A., A Sand County Almanac, Oxford University Press, 1949. Myers N., “The Sinking Arc”, in D. Van De Veer (Ed), People, Penguins, and Plastic Trees: Basic Issues in Environmental Ethics, Wadsworth, 1986, pp. 111–119. Regan T., The Case for Animal Rights, Routledge, 1988. Russow L., “Why do Species Matter?”, in D. Van De Veer (Ed), People, Penguins, and Plastic Trees: Basic Issues in Environmental Ethics, Wadsworth, 1986, pp. 119–126. Singer P., Animal Liberation (2nd ed), Thorsons, 1991.