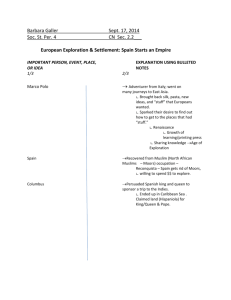

recognition and support of iccas in spain

advertisement