A Sketchbook of Production Problems

advertisement

Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1991

A Sketchbook of Production Problems

Kathryn Bock1

.

Accepted February 5, 1991

This paper sets out five problems of language production that dominate current research

in the area. Four of them are problems that the f o d a t o r must solve in order to carry

out its functions. Consideration of these problems has spawned different theoretical

perspectives on and a variety of empirical findings about how the formulator works, and

these are briefly surveyed. The fifth problem is metatheoretical, and concerns the proper

domain of production theory.

The purpose of this paper is to identify some of the major themes in

research on language production. Over the past 15 years or so, work in

this area has rapidly made the transition from a psycholinguistic hobby

to a central enterprise in the study of language performance. Although

the focal problems are in many ways similar to those of language comprehension, there are important differences that help to make the study

of production distinct. I will sketch five problems, starting with the one

that serves as a major force in dividing the issues of production from

those of comprehension, and briefly illustrate how these problems have

been addressed in current theory and research. Four of the problems are

This paper is adapted from a talk that introduced the Special Session on Language

Production at the Third Annual CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing. 1

am grateful to the other participants in the session (Gary S. Dell, Merrill F. Garrett,

W.J.M.Lcvelt. David D. McDonald. and Stcfanie Shattuck-Hufnageo for their contributions to this paper, and to Janet D. Fodor for making time stand still. Preparation

of the manuscript was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (BNS8617659) and the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD21011).

' Address all correspondence to Kathryn Bock, Department of Psychology, Psychology

Research Building, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-11 17.

141

0090.690519 1/0500-014 1106.50/0 0 1991 Plenum Publishing Corporation

142

Production P r o t

Bock

processing challenges that the production system must meet, and the last

is a question about the domain of a production theory.

Presenting the big problems requires a solution to a little problem

of terminology. There is no very satisfactory label in general use for the

cognitive apparatus that is responsible for producing language. The natural complement to the parser would seem to be the articulator, an

apparatus that joins pieces together into systematic units. But that term

is ambiguous and, in its dominant meaning, too toothy and lippy to

adequately capture the higher-level linguistic processes that give rise to

speech. As an alternative, I will refer to the formuiator, borrowing the

term from Levelt's compleat introduction to the problems of production

. - . . - -.-(Levelt, 1989).

.--.

THE FIVE PROBLEMS

The five sections that follow present the five problems. In order,

they are (1) getting the form right; (2) regulating information flow; (3)

fluency; (4) coordination; and (5) type transparency.

Regulating In)

Getting the Form Right

The goal of comprehension is to create an interpretation of an utterance. The goal of production-at least the speaker's immediate goalis simply to create an utterance. That utterance should be adequate to

convey the speaker's meaning, but it must also meet a range of constraints that we think of in terms of the grammar. And that gives the

production problem a different spin. As Garrett (1980) put it, "The

production system must get the details of form 'right' in every instance,

whether those details are germane to sentence meaning or not." So, a

very general problem for a theory of production is to explain how speakers create linguistic structures at all levels.

This difference between production and comprehension can lead to

somewhat different evaluations of the role and the importance of structure

in general, as well as structures in particular. Subject-verb agreement

offers an illustration. This type of agreement carries little of the burden

of interpretation in English, and in line with this, there are studies of

comprehension which show that readers are all but oblivious to agreement

violations such as Some shells is even soft at the same time that they are

keenly aware of the problem with Sometimes the diamondback swims in

the open sea but it usually lives in salt shakers and tidal rivers (Kilborn,

1988; Kutas & Hillyard, 1983). This tends to engender the idea that

agreement is

surprisingly st

In several expi

conditions knt

ments 1 and 2

they could ha'

In genera

Tape-recorded

prone than in

fences, Deese

yielding a rate

sentences. Otl

and word-leve

of spontaneou

ishingly low. '

of form right.

\

Somewhi

creating acce]

leads to a pro1

like this: A s

respect, has ey

tures and inte

The speaker r

pretation. Thc

creating a stn

sequence, we

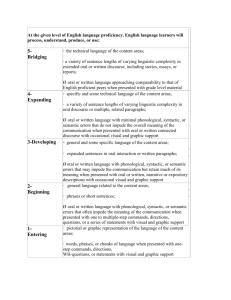

Table I. Estirr

the Deese (I!

Corpus

Deese (1984)

London-Lund

2

Brian MacWhi

for the speaker

143

production Problems

agreement is all but irrelevant to the use of English. Yet speakers are

surprisingly scrupulous in their observation of subject-verb agreement.

In several experiments that were designed to elicit agreement errors under

conditions known to predispose them. Bock and Miller (1991. Experiments 1 and 2) observed errors in less than 5% of the utterances in which

they could have occurred.

In general, speakers are very good at creating acceptable utterances.

Tape-recorded corpora reveal that everyday speech is much less errorprone than intuition might suggest. In a corpus of nearly 15,000 sentences, Deese (1984) found just 77 that could not be parsed sensibly.

yielding a rate of just five serious structural anomalies for each thousand

sentences. Other errors are also rare. Table I gives the rates of soundand word-level errors per 10,000 words from two tape-recorded corpora

of spontaneous speech. Though the rates differ slightly, both are astonishingly low. The production system does. in fact, tend to get the details

of form right.

Regulating Information Flow: The Full-Deck-of-Cards Paradox

Somewhat strangely, speakers actually may be more successflil at

creating acceptable forms than at conveying intended messages. This

leads to a problem that I will call the full-deck-of-cards2 paradox. It runs

like this: A speaker knows the communicative intention and. in that

respect, has every advantage over comprehenders, who must piece structures and interpretations together from degraded and ambiguous input.

The speaker merely has to create structures that convey a known interpretation. The paradox is that speakers can be simultaneously adept at

creating a structure and inept at conveying an interpretation. As a consequence, we get a central fact about speech errors: They obey structural

Table I. Estimated Rates per 10,000 Words for Sound and Word Errors from

the Deese (1984) and London-Lund (Gamham. Shillcock. Brown, Mill, &

Corpus

-

Dcese (1984)

London-Lund

Cutler. 1982) Corpora of Spontaneous Speech

Estimated rates per 10.000 words

Sound errors

Word errors

.1.3u

e

,

.

3.20

2.50

5.10

.

.

.-

.

Bock

Produ

constraints at the same time that they egregiously violate the intended

to m:

flow

One of the best-known structural constraints concerns form classes.

The form-class constraint i s reliably illustrated in such errors as word

exchanges, when two words transpose (e-g., The speakers of the minds

of that community, in which minds and speakers traded places); semantic

substitutions, in which a word that means something similar to the intended word substitutes for it (e-g., Until now, just do it, where now

replaces the intended word then); and phonological substitutions, in which

a word that sounds similar to the intended word substitutes for it (e-g.,

He's the kind of man that soldiers look up toand try to emanate, where

emanate replaces emulate). None of the sample errors successfully conveys the speaker's intended meaning, but all of them obey syntactic

constraints, because the words that interact in creating the errors represent

the same form classes (for word exchanges, between 80% and 85% of

spontaneous speech errors obey the form-class constraint, and for word

substitutions, nearly 100% represent the form class of the intended word;

Garrett, 1980; Stemberger, 1985).

Errors that involve bound morphemes rather than full words (e-g.,

It'll get fast a lot hotter i f you put the burner on, when hot a lot faster

was intended) likewise obey syntactic constraints as a result of affix

stranding: Only the word stem moves (this is true for approximately 90%

of such errors; Stemberger, 1985). In similar fashion, sound-level errors

obey phonotactic constraints, creating acceptable phonological structures. So, analogous to the form-class constraint, there is a sound-class

constraint on errors: Consonants interact with other consonants (e.g.,

Jashon and Josua when Jason and Joshua was intended), and vowels

with other vowels (e.g., surplus accipital activity when occipital activity

was intended) and originate in the same positions in words or syllables.

The full-deck-of-cards paradox may be more apparent than real,

though, because "playing with a full deck" may not be an especially

good thing for a speaker who is forced by the constraints of the vocalauditory channel to say one thing at a time. If one knows, at some level,

much more than one can conveyat a given moment, a great deal of work

must go

into not saying a lot of things, in order to say the right things

at the right time. The availability of information other than that which

is actually spoken and the deleterious potential of that availability are

evident in the prevalence of contextual errors-errors more often than

not have an identifiable source somewhere in the intended utteranceand in the predominance of anticipatory over perseveratory errors. So,

begir

flood

rett's

1988

repre

spon

built

item:

func

t (V)(

this

thou

the 1

. ogic

,the 1

tern

fransion

4

!

:

1

I

!

,

..

.I1

1

I

I

.

gwe

Dell

retri

I

h

an<

inf

is

for

int

19

!

P"

an

cl;

fre

ne

[hi

AI

sa

PC

production Problems

I

I

b

i1

I

145

to mix metaphors, the full deck of cards gives rise to a torrent whose

flow must be continuously regulated.

But there are leaks. And those leaks, in the form of speech errors,

begin to reveal the design of the machinery that ordinarily controls the

flood. One influential analysis of errors is that of Merrill Garrett. Garrett's analysis motivates a model of the production process (Garrett,

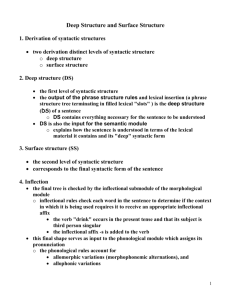

1988) that is shown in Fig. 1. Briefly, there are three levels, the topmost

representing the intended message. The remaining two levels are responsible for putting the linguistic pieces of utterances together. One

builds the functional-level representation by assigning selected lexical

items from the lexical set to syntactic functions within clauses; these

functions are represented a s the slots in the functional structure

((V)(S(V)(N)(N))). The phonological forms of words are irrelevant to

this assignment, as is the eventual order of the words in the utterance,

though the form classes of words are critical. The second level creates

the positional-level representation, where both word order and phonological forms are specified within phrases. Word forms are retrieved from

the lexicon and their segmental and prosodic features are assigned to the

terminal elements of the constituent structure or positional-level planning

frame (see Shattuck-Hufnagel, 1979, 1987, for a more detailed discussion of how this second level might be o r g a n i ~ e d ) . ~

The levels of the model neatly explain the complex error, The skreaky

p e a s e gets the wheel, which was observed by Garrett4 and analyzed by

Dell (1989) in the following fashion. Initially, wheel and grease are

retrieved from the lexical set and assigned the wrong syntactic functions

I

I have omitted a controversial set of processes that follow the assignment of segmental

and prosodic structure. In Garrett's scheme these processes interpret and site node

information (Ganett, 1988). that is, they insert the elements of the closed class. There

is considerable disagreement about whether the phonological interpretation of these

forms is different from that of the open class (see Dell. 1990). whether the forms are

inherent in positional frames in the way that this mechanism seems to require (Bock,

1989). and whether the closed class constitutes a separable vocabulary of the language

processor, as their peculiar vulnerability in aphasic disorders seems to suggest (aphasics

are generally better at dealing with high- than with low-frequency words, but closedclass words are disproportionately absent from aphasic speech despite their very high

frequencies of occurrence in normal speech; Garrett, 1990). Garrett (1990) presented

new evidence from speech errors to counter the hypothesis that it is word frequency

that is responsible for most of the differences between the open and closed classes.

Among those word-exchange errors involving open- or closed-class words from the

same frequency ranges, open-class errors predominated.

' Personal communication. November 1, 1988.

J

Production Problems

Bock

7

Inferential processes

Message representation

of functional

structures

selection

1

{

Lexical'assignment

t

Functional level representation

\

.

,

Ñ

Assignment of segmental and

prosodic structure for words

Positional level representation

Fig. 1. A model of language production (slightly modified from Garrett, 1988).

in the functional structure (wheel becomes the object and grease the

subject). That functional error eventuates in the placement of grease in

the same phrase wil

frame, and sets up

and HI. That excha

This analysis

rationalizing error 1

ambitious. It is als

tion. The need to 1

and the model's ml

this is achieved. Ji

modularity (Fodor,

modular, since it m

are capable of exp

many errors is enol

far downstream. C

severe restriction c

that level are sensi

A related rest

Because everythin

discrete stages of

up influence f r o m

retrieval side, one

errors that have be

and Levelt (1983)

mother for wife, i

phonological WOK

catalog, consider4

rett, 1988). Like\

ological affinities

(1981) and Marti

occurrence of phc

ceeds chance exp

the levels of lexi

of the lexicon in

composition can

thereby making 11

errors (for differ1

1991; Schriefers,

Despite its i

of lexical retriev

that there are un

the syntax and a

Production Problems

147

the same phrase with and next to squeaky in the positional-level planning

frame, and sets up the conditions for the sound exchange between /w/

and /r/. That exchange in turn yields sbeaky gwease.

This analysis illustrates something about the theory's successes in

rationalizing error patterns, but the model's goals are considerably more

ambitious. It is also intended to explain the features of normal production. The need to regulate the flow of information is one such feature,

and the model's modular design constitutes a strong proposal about how

this is achieved. Jerry Fodor pointed out in a footnote to his essay on

modularity (Fodor, 1983) that it makes little sense for production to be

modular, since it must be open to the full range of information that people

are capable of expressing. Sense aside, though, the weird semantics of

many errors is enough to suggest that this openness does not extend very

far downstream. Garrett's model proposes that, at each level, there is a

severe restriction on the kinds of information to which the operations at

that level are sensitive.

A related restriction is evident in the direction of information flow.

Because everything proceeds from the top down, there are relatively

discrete stages of semantic and phonological retrieval, with no bottomup influence from the positional to the functional level. On the lexical

retrieval side, one argument for this is found in the word substitution

errors that have been discussed by Garrett (1980), Fay and Cutler (1977),

and Levelt (1983): Semantic word substitutions (e-g., sword for arrow,

mother for wife, listen for speak) show few similarities in form, while

phonological word substitutions (mushmom for mustache, cabinet for

catalog, considered for consisted) show few similarities in meaning (Garrett, 1988). Likewise, exchanged words d o not seem to have the phonological affinities that exchanged sounds do. However, Dell and Reich

(1981) and Martin, Weisberg, and Saffran (1989) have shown that the

occurrence of phonological similarities among semantic substitutions exceeds chance expectations, leading to questions about the strictness of

the levels of lexical retrieval. Dell (1986) has proposed that the levels

of the lexicon interact during retrieval, so that a word's phonological

composition can affect the accessibility of its semantic representation,

thereby making lexical processing a major culprit in the leaks that yield

errors (for different perspectives, see Butterworth, 1989; Levelt et al.,

1991; Schriefers, Meyer, & Levelt, 1990).

Despite its differences from Garrett's model over the mechanisms

of lexical retrieval, Dell's model shares with Garrett's the assumption

that there are uniform levels of syntactic construction, thereby making

the syntax and other structural processes the major regulators of infor-

148

Bock

mation flow. If this assumption is right, supposed message-level features

should have little effect on structural processes at the positional level. In

line with this prediction, there are results which suggest that the processes

that construct hierarchically and serially arranged sequences of words are

not directly sensitive to the semantic or pragmatic burden of sentence

constituents.

Much of this evidence rests on a structural priming phenomenon

which appears to reflect the process of creating constituent structures.

The phenomenon itself is simply a tendency to produce sentences in

structures similar to those of recently produced sentences. This tendency

appears to persist regardless of changes in discourse structure (Estival,..

1985), changes in the thematic roles of the sentence constituents (Bock

& Loebell, 1990), changes in the semantic features of the sentence constituents (Bock, Loebell, & Morey, in press), and changes in the closedclass elements in the sentences (Bock, 1989). It disappears after a change

in the constituent structures of the sentences involved (Bock & Loebell,

1990), even when metrical structures are held constant. The implication

is that the processes that form the positional representation, building the

bridge from the functional to the positional level, operate without the

guidance of message features. This accords with the idea that the flow

of information during production may be regulated by heavily restricting

the access of processes to different types of information.

The obverse of the problem of regulating information is the problem

of fluency. Though it may be essential to restrict the top-down flow of

information during production in order to reduce interference from extraneously or contemporaneously available information, it is also important to keep speech flowing smoothly, without long hesitations and

interruptions (Clark & Clark, 1977). Speakers are not entirely successful

at doing this, of course, but the rate at which speech is produced is

nonetheless impressive. Levelt (1989) emphasizes just how big a feat it

is: At a normal speaking rate, speakers select a word roughly once every

400 ms from a vocabulary that he puts in the range of 30,000 words.

Because of the normal fluency of speech, it is natural to assume

that the formulator is organized and operates in a way that meets the

demands of creating utterances in time. This has the potential to conflict

with the need to regulate information during production. On one side,

the formulator must staunch the flow of information, and on the other,

keep it moving.

To see the problem, consider a possible implication for fluency of

Production Problems

,

!

I

I

the organization of the model in Fig. 1. In order to ensure that only

information which can be integrated into the developing utterance is

passed to the next processing level, suppose that the functional representation of each utterance is fully formatted before positional processing

commences, and the positional representation fully formatted before motor programming commences, and the motor program fully formatted

before articulation commences. If so, speech might typically proceed in

bursts punctuated by silence, as each utterance is formulated from the

functional level on down. This violates the intuitions of both speakers

and hearers.

--- . .

Part of the formulator's solution to the problem seems to be to

specify progressively narrower windows or units at each level, creating

a processing hierarchy. In terms of the model in Fig. 1, the units at the

functional level are larger than those at the positional level, and so on

down, allowing an utterance to be initiated without being fully prepared

at every level. On the basis of speech-error evidence, Garrett (1988)

proposed that the functional level spans about two clauses, while the

positional level spans about a phrase. The error evidence is found in the

typical scope of word exchanges, which is generally no more than two

clauses, and the typical scope of sound exchanges, which is generally

no more than a phrase. Since word exchanges seem to be consequences

of syntactic-function misassignments and sound exchanges seem to be

consequences of phonological-segment tnisassignments, the scope of such

errors offers one index of the scope of the operations that normally

perform these tasks (also see Ford, 1982; Ford & Holmes, 1978). Other

evidence comes from experimental findings which show that the meanings of both the subject and the object of a to-be-spoken sentence may

be active at a point in time when only the phonological form of the head

of the subject noun phrase is active (O'Seaghdha, Dell, & Peterson,

1988). At lower levels, the processing windows may be narrower still.

Stemberg, Knoll, Monsell, and Wright (1988) offer evidence from studies of planned speech that the stress group or metrical foot (a single

stressed syllable and its accompanying unstressed syllables) is the basic

unit of the motor program.

Consistent with such a hierarchical arrangement, the units at different levels seem to interact differently with the realization of grammatical

features. Bock and Cutting (1990) explored the occurrence of subjectverb agreement errors following phrasal vs. clausal subject-postmodifiers

(e.g., The claim about the newborn babies. . vs. The claim that wolves

had raised [he babies. . .) in which the lengths of the postmodifiers were

equated in number of syllables. In these experiments, the task was simply

.

Production Problems

Bock

IS0

to produce a completion for each sentence fragment, and the dependent

measure was the number of verb-agreement errors that speakers produced

in their completions (see Bock & Miller, 1991). Extrapolating from find- .

ings in comprehension (Caplan, 1972; Jarvella, 1971), the prediction

would be that such errors should be more frequent after clauses than after

phrases, due to a general tendency to forget the form of material preceding the most recent clause. The hierarchical formulation hypothesis

predicts just the opposite. Grammatical agreement is defined over clauses

and, on the assumption that clauses constitute a unit of formulation at

the level at which agreement is implemented (the functional level, where

subjects are specified), agreement should be relatively uninfluenced

.

.-.

-by . .---material outside the clause in which a given verb occurs.

The actual result was in line with the hierarchical hypothesis: Speakers made significantly more errors after phrasal than after clausal postmodifiers. Notice that the erroneously agreeing verb in The claim about

the newborn babies were. . . i s in the same clause with the apparent

source of the error, whereas in The claim that wolves had raised the

babies were. . the erroneously agreeing verb is in a different clause,

the matrix clause. If clauses constitute a formulation unit, such that the

contents of constituent phrases within a clause are free to interact in a

way that the contents of constituent phrases from different clauses are

not, the agreement-error results follow.

From a theoretical standpoint, the specification of such units is essential to meaningful contrasts between modularity and interactivity in

production (or any fluid ability). In a modular system, processes are

defined in terms of the vocabularies or information types to which they

are responsive, and in a constructive modular system, one process must

hinge on another, with one's product serving as the other's raw material.

T o empirically distinguish such an arrangement from an interactive

processing system, there must be some specification of the scope of each

process that predicts the points at which different types of information

come into play.

.

Coordination

The coordination problem arises because production is, in fact, productive: The utterances we produce are rarely memorized sequences, but

rather creative assemblies of elements within structures. Words must be

put into place in syntactic structures, and sounds must be put into place

within phonological structures. The problem is evident in the architecture

of the model in Fig. 1: At the functional level the members of the lexical

set must be assigned to the proper syntactic functions, and at the posi-

tional level the phc

into the right place

The argumenl

of coordination fir

other elements of

shows that words

than other units su

is that such eleme

structures,

are

processing but

system

1

t

Another argi

nomenon of accoi

tures appropriate t

rightly to bear th

subject function.

w e can rarely de

when pronouns a;

the world should

rett, 1980). Sim

tioned, they see

environment. In

tended; Fromkin

1

*

iI

i

I

..

. .'*'

<r '

.

..-

SENTENCE

.

PHRASI

f

'*Â

..

.

2'

fc

1

i

"

->

WORt

MORPHEM'

>SYLLABL

g

SYLLAEL

Â

VCORC

CLUSTE

f

PHONEN

FEATUF

Fig. 2. Percentage

similar graph pres

should be used foi

151

Production Problems

tional level the phonological segments of the word forms must be slotted

into the right places.

The argument that words and phonological segments are the targets

of coordination finds support in evidence that they are more likely than

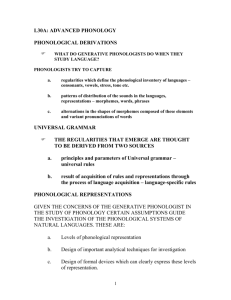

other elements of utterances to turn up in the wrong places. Figure 2

shows that words and segments are more likely to participate in errors

than other units such as phrases or features or syllables. The implication

is that such elements are not retrieved as pans of larger, more unitary

structures, but are manipulated, placed, and misplaced as pieces by the

processing system.

Another argument for a coordination process comes from the phe-nomenon of accommodation, in which misplaced elements take on features appropriate to their environment. For example, something that ought

rightly to bear the object function might be inadvertently assigned the

subject function. Because English does not routinely mark case overtly,

we can rarely detect case-marking accommodations, but they do occur

when pronouns are involved, as in the error He offends her sense of how

the world should be (when She offends his sense.

was intended; Garrett, 1980). Similarly, if phonological segments are improperly positioned, they seem to take on the features appropriate to the new

environment. In the error lumber s p a m (when slumber party was intended; Fromkin, 1973) a word-initial /p/ mistakenly follows the initial

/

.

..

oe

0

>SYLLABLE

SYLLABLE

VCORCV

SOUND UNITS

--

FEATURE

0

I

I

I

10

20

30

40

PERCENTAGE OF ERRORS

Fig. 2. Percentages of speech errors involving various linguistic units (modeled after a

similar -graph

. presented by Dell. 1987). The percentages are rough approximations and

should be used for ordinal comparisons only.

'

-

-

Production Problem

Bock

/sf, and the Ipf should no longer be aspirated. The implication here is

that various structural positions or relations impose requirements on the

elements that fill them, requirements that are not features of the elements .,

themselves.

T o solve the coordination problem, the formulator must know how

to put the pieces of language into their proper places in utterances. Naturally, the pieces that have received the most attention in efforts to

explain how the formulator solves this problem are those pieces that most

obviously require coordination, words and sounds.

Words themselves have two logically separable components, a

meaning and a phonological form. As a result, we have the same meaning

expressed in different phonological forms (e.g., pail a i d bucket) andm---different meanings expressed in the same phonological form (e-g., savings bank and river bank). If these components are represented separately

as well, their coordination with the relevant structures may also be a

twofold affair. Again in terms of the model in Fig. 1, abstract specifications of words (presumably including their semantic specifications, but

not their phonological specifications) are hypothesized to b e linked to

syntactic functions at the functional level, but the sound segments are

not put into place until the positional representation is constructed.

. !

One orediction that follows from dividing the coordination pioblem

.iI

up in this way is that variations in the states of preparation of the mean. '\ .

.

n g s of lexical entries should have a greater impact on the syntax of an

utterance than variations in the states of preparation of the phonological . . '

forms of words. The prediction follows from the role of the functional

representation in guiding the creation of a syntactic structure, via assignments to such syntactic functions as subject and direct object.

This was tested in two experiments that compared the effects of

semantic and phonological priming on the arrangements of words in

sentences (Bock, 1986). The participants received priming words that

were either semantically or phonologically related to various target words,

under conditions that disguised the priming manipulation. T h e target

words appeared as the subjects or objects of sentences that were extemporaneously created by the participants themselves to describe pictured

events which followed the presentation of the priming words. For example, one speaker might have received the word thunder followed by

a picture of lightning striking a church, while other speakers received

the words worship, frightening, or search. The two target words were

Zighming (semantically primed by thunder and phonologically primed by

frightening) and church (semantically primed by worship and phonologically primed by search). The question was whether the subject and

'

object assignment

varied (and along

on whether the a;

The results s

tion assignments

mantically prime'

an active or passi

primed targets w

were primed tha

,

meanings of woi

differential prim

,

effect.

This result

ordination. Howl

of the phonologi

on functional as

work (Bock, 191

reliable effect o

assume, in line 1

effects on semar

- " ..

lexical errors, t

- , activation of ph

in the lexical se

-- . tional structure.

KT-'-proceeds in dis

**.

-Ç.-"

* r.ff- form.

'Phonologi(

.-..I

'ical o r phonolo;

and some deba

the phonologic:

the odd fact th

stored word fc

should occur (

words). Why s

I

Shattuck-1

!

occurs

because

!

that transform

are misplaced

developing mt

Evidence for t

ences between

8

. , ' J

;

¥È

,.Ã̂

"

I

Production Problems

153

object assignments in the sentences that were produced by the participants

varied (and along with them, the structures of the sentences), depending

on whether the agent (lightning)or recipient (church) was primed.

The results suggested that semantic priming affected syntactic-function assignments in a way that phonological priming did not. The semantically primed target reliably tended to serve as the subject of either

an active or passive sentence, as appropriate, whereas the phonologically

primed targets were not used as subjects reliably more often when they

were primed than when they were not. So differential priming of the

meanings of words may change their functional level assignments, but

differential priming of the sounds of words did not have as strong an

.- . . - -.-effect.

This result is clearly consistent with the model's conception of coordination. However, the model also predicts that the state of preparation

of the phonological forms of words should have no influence whatsoever

on functional assignments, and this turns out to be too strong. In other

work (Bock, 1987), I have found that phonological priming can have a

reliable effect on sentence form. One way to accommodate this is to

assume, in line with Dell and Reich's (1981) explanation of phonological

effects on semantic substitutions, word exchanges, and other higher-level

lexical errors, that such interactions are mediated by the lexicon: The

activation of phonological forms affects the state of any affiliated items \

in the lexical set, which may in turn affect the determination of a functional structure. This requires weakening the view that lexical retrieval

proceeds in discrete stages involving the access of meaning and then

form.

Phonological coordination, the problem of putting sounds into lexicai or phonological structures, is currently the object of intense scrutiny

and some debate. Especially at issue is a question about the nature of

the phonological planning frame, a question which follows in part from

the odd fact that phonological segments move despite the existence of

stored word forms which specify the order in which sound segments

should occur (forms that allow us, among other things, to recognize

words). Why should sounds move around at all?

Shattuck-Hufnagel (1987; also see Levelt, 1989) suggests that this

occurs because connected speech requires building a metrical structure

that transforms the phonological segments in various ways. Segments

are misplaced when they are copied from the stored template into the

developing metrical structure, which incorporates the planning frame.

Evidence for this view comes from experimentally demonstrated differences between errors that arise in the production of disconnected words

Bock

Product!

and those that occur in connected speech (Shattuck-Hufnagel, 1987). In

the former, there were a disproportionate number of word-onset errors

relative to errors in other word positions, while in the latter, more errors

appeared for non-onset consonants.

Dell (1986) also proposed a coordination mechanism in which sound

segments are associated with phonotactic frames, although the segmentretrieval mechanism was modeled as a process of spreading activation in

a lexical network. Dell (1990), in contrast, has developed a paralleldistributed-processing model (similar to that of Jordan, 1986) in which

frames are epiphenomenal, an emergent property of the features of the

stored segments and the network in which they'are represented. According to this model, the frame-like regularities of errors are a product of

the similarities and the sequential biases characteristic of segment combinations in English. This redefines the coordination problem, since segments sprout frames rather than having to be attached to them.

Dell's (1990) new model is designed to simulate the qualitative and

quantitative features of noncontextual sound errors, errors that have no

obvious source in the immediate linguistic environment, and its performance on that score is impressive. It remains to be seen whether the same

architecture is adequate to account for the more common contextual errors, whose distribution and features were the focus of Dell's earlier

effort (1986). Dell (1990) suggests that the error types may, in fact, be

disparate. If so, the coordination problem remains.

tional

distingi

154

Type Transparency

.

The question of type transparency (Berwick & Weinberg, 1984),

applied to production, is whether the organization of the formulator mirrors the logical organization of rules and structures in the grammar. There

seems to be an irrepressible desire on the part of many linguists and

psycholinguists to equate the components of production models with the

components of one or another syntactic theory, partly due to a confusion

of the behavioral notion of generation with the mathematical notion of

generation that is relevant to generative grammar. They are distinct.

There are other divergences, too. Garrett (1980) noted that errorbased production models (including his own) are grounded in a type of

data that is dramatically different from traditional linguistic evidence.

For that reason, the model is agnostic about many things. T o take one

example, the functional-level representation in Fig. 1 is not equated with

any of the plausible candidates from linguistic theory (e.g., D-structure

or S-structure in government-binding theory; f-structure in lexical-func-

BI

goals n

linguis

of inqi

veridic

vergen

ticipatt

(1985)

error d

similai

dornai

which

media

-

7

,

betwe

tions 1

manif

theref

ance

There

\ - aPPea

poten

& St(

sake 1

perf0

sourc

. the n

prod1

the01

lang~

corn]

Bevt

nisrr

tal 2

rece

way

anal

doni

Production Problems

,

155

tional grammar), because the error data do not provide any grounds for

distinguishing among them.

But as Garrett (1980) also noted, the differences in methods and .

goals make those similarities that do arise between production theory and

linguistic theory all the more important. Whenever such disparate lines

of inquiry converge on such similar pictures, one's faith in the picture's

veridicality increases. Fromkin's (1971) classic paper detailed the convergences between the units of linguistic theory and the units that participate in speech errors. Fromkin (1971), Garrett (1975), Sternberger

(1985), Dell (1986), and others have found that an explanation of the

error data requires separating the domains of formulation along lines very. . .

similar to the partitions found in most linguistic theories: There is a

domain in which sentence structures are formed (a syntax), a domain in

which sound structures are formed (a phonology), and a domain that

mediates between the two (a lexicon or morphology).

Though it is possible to construct much more fine-grained analogies

between theories of production processes and theories of grammar, questions have been raised about how directly our knowledge of language is

manifested in or adapted to our use of language (Chomsky, 1986) and

therefore about how responsive a linguistic theory should be to performance data or, for that matter, a performance theory to linguistic data.

There is no consensus about this in linguistics, though some linguists

appear to regard the study of language processing as a relevant and

potentially valuable source of evidence about language structure (Ades

& Steedman, 1982; Bresnan, 1978; Bresnan & Kaplan, 1982). For the

sake of consistency, at least, any linguist who regards children's language

performance (almost always, children's language production) as a central

source of evidence about how language is represented must acknowledge

the relevance of adult language performance (including adults' language

production).

In psycholinguistics, there is considerable scepticism that linguistic

theory will have anything to say about the fundamental mechanisms of

language processing, in part due to the failures of earlier efforts to adapt

competence theories to the domain of language performance (see Fodor,

Bever, & Garrett, 1974, for a summary). Because performance mechanisms are beyond the reach of introspection and intuition, an experimental approach is required to tap processing in ongoing time. Still, the

received view is that the processing system must be organized in such a

way that i t yields the structural regularities that emerge from linguistic

analyses (Fodor and Garrett, 1966). Although relatively little has been

done by way of casting alternative linguistic construals of language struc-

156

Bock

tures into production hypotheses (though see Bock et al., in press; Stemberger, 1990), it can be expected that linguistic theory will serve as an

important influence on the development of models of the formulator. The

obvious reason is that an explanation of structure is the focus of linguistic

theory, and an explanation of the creation of structure is the focus of

production theory.

CONCLUSION

The foregoing collection of sketches sets out some, but by no means

all, of the focal problems in research on language production. These

problems are sometimes judged to be either less open to solution or less

interesting (or both) than the problems of language comprehension, and

one purpose of this sketchbook has been to try to counter such impressions.

The study of production has certainly been more trying than that of

comprehension. It has gone forward thanks primarily to the tenacity and

creativity of a few dedicated collectors of speech errors, who enjoy one

advantage. Whereas the heavy industry of the study of parsing is devoted

to the development of ingenious means for tapping into ongoing processes,

formulation has the convenient property of wearing its ongoing processes

on its sleeve: In both fluent and dysfluent speech, we have direct access

to the final products of the formulator. Though w e assuredly do not have

perfect access to the underlying details, either as introspective speakers

or as curious investigators, w e often have readily observable indications

of where and when in the development of an utterance things are proceeding smoothly and where and when they are not, and in errors, w e

can sometimes detect the actual source of the disruption.

But the successful construction and interpretation of processing models

rests on the deployment of carefully targeted experimental methods. As

valuable as the analysis of spontaneous speech errors has been in establishing the bedrock regularities of formulation, the enterprise is limited

in its ability to evaluate competing hypotheses. The linguistic and extralinguistic contexts of natural errors may vary freely in ways that bear

both on the occurrence of error and on the validity of different explanations, making some form of experimental control essential. That has

been a sticking point in the development of research on language production, but pathways have begun to open with the invention of an array

of methods for the study of phonological, lexical, and syntactic encoding.

Despite the problems that it poses for the investigator, from the

Bock

>&emas an

. The

ist tic

1s of

cans

Tiese

less

and

sresat of

and

one

oted

ises,

sses

cess ,

i ave

kers

ions

prowe

dels

As

tabited

ex)ear

)lahas

iroray

"g-

the

Production Problems

157

standpoint of the language user it may seem that production is inherently

less challenging than comprehension. The fascination of the puzzle of

comprehension comes from our mysterious ability to solve a problem

with two unknowns: At the beginning of an episode that ends in understanding, the listener knows neither the meaning nor the form in which

it will be conveyed, and the process of solving for both is extraordinarily

vexed. The fascination of the puzzle of production comes from our mysterious inability to solve a problem that is, from a computational perspective, trivial (Ristad, 1990): Given a message to be conveyed, perfect

forms can be generated by any of many different algorithms. Human

speakers are, indeed, good at generating perfect forms. The mystery is

that those forms can have annoyingly little to do with the intended meaning.

The importance of a solution to this puzzle goes beyond its implications for our understanding of production itself. Explaining how the

language processor works in a domain where structures can be formed

on the basis of relatively rudimentary features of meaning may help in

explaining how structures can be formed when the meaning is, in fact,

unknown. In this sense, the explanation of production may contribute to

an explanation of comprehension as well as to the development of a

general theory of language performance.

\

REFERENCES

Ades, A. E.. A Steedman, M. J. (1982). On the order of words. UngwStics and Philosophy, 4 , 517-558.

Berwick, R. C., & Weinberg, A. S. (1984). The grammatical basis of finguistic perfonnance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bock, J. K. (1986). Meaning, sound, and syntax: Lexical priming in sentence production.

Journal of ExperUnental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12, 575586.

Bock, J. K. (1987). An effect of the accessibility of word forms on sentence structures.

Journal of Memory and Language, 26, 119-137.

Bock, J. K. (1989). Closed-class immanence in sentence production. Cognition, 31,

163-186.

Bock, J. K., & Cutting, J. C. (1990). Production units and production problems in

forming long-distance dependencies. Paper presented at the meeting of the Psychonomic Society, New Orleans, LA.

Bock, 1. K., & Loebell, H. (1990). Framing sentences. Cognition, 35, 1-39.

Bock, J. K.. Loebell, H., & Morey, R. (in press). From conceptual roles to structural

relations: Bridging the syntactic cleft. Psychological Review.

Bock, J. K., & Miller, C. A. (1991). Broken agreement. Cognitive Psychology. 23, 4593.

Brcsnan. J. (1978). A realistic transformational grammar. In M. Halle, J. Brcsnan, &

Bock

158

G. A. Miller (Eds.), Unguistic theory and psychological reality (pp. 1-59). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bresnan, J., & Kaplan, R. M. (1982). Introduction: Grammars as mental representations

.,

of language. In J. Bresnan (Ed.), The mentalrepresentaticn ofgrammaticalrelations

(pp. xvii-lii). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Butterworth, B. (1989). Lexical access in speech production. In W. D. Marsh-Wilson

(Ed.), Lexical representation and process (pp. 108-135). Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Caplan, D. (1972). Clause boundaries and recognition latencies for words in sentences.

Perception & Psychophysics. 12, 73-76.

Chomsky. N. (1986). Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin, and use. New York:

Praeger.

Clark. H. H., & Clark, E. V. (1977). Psychology and language: An introduction to

psycholinguistics. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- ----.Deese, J. (1984). Thought into speech: The psychology of a language.&g~&ood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Dell. G. S. (1986). A spreading-activation theory of retrieval in sentence production.

Psychological Review, 93, 283-321.

Dell, G. S. (1987, July). Phonological encoding in production. Lecture in the course

"Language comprehension and production" (G. S. Dell & M. K. Tanenhaus, instructors), Linguistic Society of America Summer Institute, Stanford University,

Stanford, CA.

Dell, G. S. (1989. March). Languageproduction and connectionist models of the mind.

Colloquium presented to the Department of Psychology, Michigan State University,

East Lansing, MI.

Dell, G. S. (1990, March). Frame constraints and phonological speech errors. Paper

. presented at the CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing, New York,

NY.

Dell, 0.S. (1990). Effects of frequency and vocabulary type on phonological speech

errors. Language and Cognitive Processes, 5,313-349.

Deil, G. S., & Reich, P. A. (1981). Stages in sentence production: An analysis of speech

. error data. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavwr, 20, 611-629.

Estival, D. (1985). Syntactic priming of the passive in English. Text, 5, 7-21.

Fay, D., & Cutler, A. (1977). Malapropisms and the structure of the mental lexicon.

Linguistic Inquiry, 8, 505-520.

Fodor. J. A. (1983). The modularity of mind. Cambridge. MA. MIT Press.

Fodor. J. A.. Bever. T. G.. & Garrett. M. F. (1974). Thepsychology of language. New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Fodor, J., & Ganett, M. (1966). Some reflections on competence and performance. In

J. Lyons & R. J. Wales (Eds.), Psycholinyuticspapers (pp. 135-154). Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press.

Ford, M. (1982). Sentence planning units: Implications for the speaker's representation

of meaningful relations underlying sentences. In J. Bresnan (Ed.), The mental representation of grammatical relations (pp. 797-827). Cambridge. MA: MlT Press.

Ford, M., & Holmes, V. M. (1978). Planning units and syntax in sentence production.

Cognition, 6, 35-53.

Fromkin, V. A. (1971). The non-anomalous nature of anomalous utterances. Language.

47, 27-52.

Fromkin, V. A. (1973). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton.

Production Probler

Gamham. A.. ShiIIc

Slips of the ton

Cutler (Ed.), S

Mouton.

Garrett. M. F. (197

psychology of 1

Garrett, M. F. (19s

(Ed-),

Languor

Garrett, M. F. (19

Linguistics: 77

aspects (pp. 6'

Garrett. M. F. (19'

presented at tl

NY.

Jarvella, R. J. (IS

Learning and

Jordan. M. I . (198

machine. Pro1

Society (pp. 5

Kilbom. K. (1988

behavioral an

and granvruit

cholinguistik,

Kutas, M.. & Hill:

and semantic

W e l t , W. J. M.

W e l t , W. J. M.

MTT Press.

M e l t , W.J. M-,

J. (1991). Th

naming. Psyi

Â¥MartinN.. Wei:

occurrence o

of Memory a

O'Seaghdha, P . (

resentations

chonomic S(

Ristad, E. S. (19'

at the CUN'

Schricfers, H., N

lexical acce:

Memory am

Shaituck-Hufnag

in sentence

processing:

Hillsdale, f

Shattuck-Hufnag

planning: F

Production Problems

159

Garoham, A., Shillcock, R. C. Brown, G. D. A., Mill, A. I. D.. & Cutler, A. (1982).

Slips of the tongue in the London-Lund corpus of spontaneous conversation. In A.

Cutler (Ed.), Slips of the tongue and language production (pp. 25 1-263). Berlin:

Mouton.

Garrett, M. F. (1975). The analysis of sentence production. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The

psychology of learning and motivation (pp. 133-177). New York: Academic Press.

Garrett. M. F. (1980). Levels of processing in sentence production. In B. Butterworth

(Ed.), Language production (pp. 177-220). London: Academic Press.

Garrett. M. F. (1988). Processes in language production. In F. J. Newmeyer (Ed.),

Linguistics: The Cambridge survey, HI: Language: Psychological and biological

aspects (pp. 69-96). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Garrett, M. F. (1990. March). Processing vocabularies in language production. Paper

presented at the CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing, New York,

NY.

Jarvella, R. J. (1971). Syntactic processing of connected speech. ~ournaiof Verbal..

Learning and Verbal Behavior, 10, 409416.

Jordan, M. I. (1986). Attractor dynamics and parallelism in a connectionist sequential

machine. Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science

Society (pp. 531-546). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kilborn, K. (1988). A note on the on-line nature of discourse processing: Comparing

behavioral and ekctrvphysiological m e a s w in I T ~ o ~ ~ I ofor

M ~ semantic anomalies

and grammatical errors. Unpublished manuscript, Max-Planck-Institut fur Psycholinguistik, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Kutas, M., & Hillyard, S. A. (1983). Event-related brain potentials to grammatical errors

and semantic anomalies. Memory & Cognition, 11, 539-550.

Levell. W. J. M. (1983). Monitoring and self-repair in speech. cognition, 14, 41-104.

Lcvelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, M A : \

MIT Press.

b e l t , W. J. M.. Schriefere, H.. Vorberg. D.. Meyer, A. S., Pechrnann, T., & Havinga,

J. (1991). The time course of lexical access in speech production: A study of picture

naming. Psychological Review, 98, 122-142.

Martin, N., Weisberg, R. W., & Saffran, E. M. (1989). Variables influencing the

occurrence of naming errors: Implications for models of lexical retrieval. Journal

of Memory and Language, 28, 462485.

O'Seaghdha, P. G.. Dell, G. S.. & Peterson. R. R. (1988. November). Indexing representations in language production. Paper presented at the meeting of the Pv chonomic Society, Chicago, IL.

Rislad, E. S. (1990, March). Obstacles to efficient languageprocessing. Paper presented

at the CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing, New York. NYSchriefers, H., Meyer, A. S., & b e l t , W. J. M. (1990). Exploring the time course of

lexical access in language production: Picture-word interference studies. Jounml of

Memory and Language, 29, 86-102.

Shattuck-Hufnagel, S. (1979). Speech errors as evidence for a serial-ordering mechanism

in sentence production. In W. E. Cooper & E. C. T. Walker (Eds.), Sentence

processing: Psychoiinguistic studies presented to Merrill Garrett (pp. 295-342).

Hillsdaic. NJ: Erlbaum.

Shat~uck-Hufnagel.S. (1987). The role of word-onset consonants in speech production

planning: New evidence from speech error patterns. In E. Keller & M. Gopnik

14

-.

.

-. ...-..

-.... . . ..--, .

-

-.

.

+

..

-

..

$4

.

*

*

.

.

. .

A , - - .

Â¥ >..

.. v-...<Â ..,....,

c$-

t

..,.-,...

,.

,.

7.

.-

,-

-^;:.:,!.. ,.;**..,

. '.;,,. .y

~^w^r

.

--'3.9$:--.:

.:s

-.

,',-a

,,

+,

,.,-

'-.',

d

c.

!Â¥^i^,';y\.

..:..: .'

-. -, .$i:~~,i$*,~.;~~.~:~-..

^^.^

..-

. ¥'"

":-<'*;

.

- ~(l+a;Ld.-,:.;

X'G

: :.:.x,+?:;$?.;y

:+:

'

c

.W.L L.,+

.-;.-,d

.w:.,.... -J?"

--...- .

.. ..

...

.

.

,.-,

,

0%

<.

-,,,-

...... - .

,.: .

. .

.-

'

Journal of P?c/

Bock

Hillsdale, NJ: Erl(Eds,), Motor and sensory processes of lungtiage (pp. 17-5

baumSlemberger, J. P. (1985). An interactive activation model of language production. In A.

Ellis (Ed.), Progress in the psychology of language (pp. 143-186). London: Erlbaum.

Stemberger, J. P. (1990). wordshape errors in language production. Cognition. 35, 123-

~

157.

Sternberg, S., Knoll, R. L., Monsell, S., & Wright, C. E. (1988). Motor programs and

hierarchical organization in the control of rapid speech. Phonetics, 45, 175-197.

On the

Evidenc

Susana del

Accepted Febn

The present sn

and phonologil

the tongue in 5

effect 'on suble

feedback-from

meaning and ft

to the hypotha

production. F

language proa

processing-sta

. !,

There are f

can be usec

process tha

one hand, 1

volving sut

of phonoio:

may lead u

This rescan

dc Investigi

ryn Bock.

Universida(

Universidai

Universida~

Address all

sidad dc 0