THE INTENSIVE ANALYSIS OF RECURRING

advertisement

PSYCHOTHERAPY: THEORY, RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

VOLUME 17, #2, SUMMER 1980

THE INTENSIVE ANALYSIS OF RECURRING EVENTS

FROM THE PRACTICE OF GESTALT THERAPY

LESLIE S. GREENBERG*

University of British Columbia

ABSTRACT: An intensive analysis of nine events in

which three clients were working on resolving 'splits'

by means of the Gestalt 'two chair method' is presented. These events had previously been shown to

contain good therapeutic process as measured by the

Experiencing Scale and the purpose of this analysis

was to discover performance patterns associated with

resolution. A model of 'split' resolution, constructed

from Voice Quality and Depth of Experiencing data

for the performances in each chair shows that resolution occurs by integration. The softening of the harsh

internal critic emerges as a key factor in resolving

intrapsychic splits. The implications of this model for

practice and research are discussed.

Research, which is both close to the clinical

phenomena and makes attempts to formalize the

phenomena in quantifiable or objective terms, is

much needed to aid the integration of 'scientific'

and 'clinical' endeavors. Empirical approaches

which enable a sense of the 'lived reality' of what

actually occurs in therapy to be maintained have

the advantage of providing research results that

are more readily applicable to clinical practice.

The intensive study of therapeutic events in an

empirical rather than an experimental way

allows one to capture the sometimes subtle

changes in performance that would be completely missed by an experimental approach. The

central goal of this study is to present a descriptive model as close to the data as possible, of

some aspects of the performances of clients engaged in the therapeutic task of resolving a 'split'

by means of the Gestalt 'two chair' method.

The importance of 'healing' splits and

polarities in human functioning has been commented on by many theorists (Bakan, 1966;

* Requests for reprints should be sent to Leslie S. Greenberg, Dept. of Counseling Psychology, University of British

Columbia, 2075 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T 1W5.

Jung, 1966; Perls, 1951; Rank, 1945). Working

on splits in functioning forms a major part of the

process of the Gestalt approach and the 'two

chair' method of working on splits is often used

in an attempt to facilitate integration. It is the

client's actual performance while engaged in

working on splits by this method that is the focus

of this study.

A 'split' has been defined as being an intherapy statement of conflict with recognizable

distinctive features (Greenberg, 1979). Statements such as "I shouldn't be so lazy" or "I

criticize myself," in which two parts of the self

are presented as being in opposition in a live

or poignant manner, indicate that the person is

experiencing a split in the moment. Three types

of splits, each representing different forms of the

presenting problem, have been identified: the

Conflict type, in which people state a conflict;

the Subject/Object type, in which people report

that they are doing something to themselves; and

the Attribution type, in which people are hypersensitive to some feature in the environment and

report it to be influencing them in a psychologically undesirable way. The clients' performances on these tasks are the subject of this study.

The definitions of the 'split' are regarded as

definitions of the psychological task in which the

person is engaged, i.e., trying to solve the split.

The subtyping of the splits may prove important

for there may be different resolution performances associated with each subtype. The therapist in this approach is construed as part of the

task environment and as providing task instructions to help aid resolution.

The particular therapist operation used for this

task is called the 'two chair' operation. The following principles have been defined (Greenberg,

1979) as representing the structure underlying

the operation and as guiding the therapist's moment by moment interventions. The five princi-

143

144

LESLIE S. GREENBERG

pies are: (1) Maintaining the Contact boundary—maintaining clear separation and contact

between the parts. (2) Responsibility—directing

clients to use their abilities to respond as the

agent of their experience in each chair. (3)

Attending—directing the clients' attention to

particular aspects of their present functioning.

(4) Heightening—highlighting aspects of present experience by increasing the level of affective arousal. (5) Expressing—making actual and

particular that which is intellectual or abstract.

The operation executed according to these principles is essentially designed to encourage the

client to unfold the inner dialogue underlying the

split in a present centered dialectical process.

There have been a number of theoretical

statements as to the nature of the clients' experience and behavior in the process of change in

Gestalt therapy that are relevant to this analysis

of the client performance in a 'split' task. The

first are those by the founder of Gestalt Therapy,

Fritz Perls. He commented on the resolution of

the top-dog/under-dog and other splits "by listening we can bring about reconciliation" of the

two parts (Perls, 1969). In a further elaboration,

he proposed that, when people listen to themselves, integration occurs through a synthesis of

polarities:

The basic philosophy of Gestalt Therapy is that of nature—differentiation and integration. Differentiation by

itself leads to polarities. As dualities, these polarities will

easily fight and paralyze one another. By integrating opposite traits we make the person whole again. For instance, weakness and bullying integrate as silent

firmness. (Perls, 1965).

and that the process is one of

the reconciliation of opposites so that they no longer waste

energy in useless struggle with each other but can join in

productive combination and interplay. (Perls, 1970).

Perls suggested that resolution occurs by a

process of listening to oneself and by a synthesis

of opposites. Polster & Polster (1976) note in

addition that each faction in the opposition

adopts different unproductive ways of dealing

with the struggle for internal unity and that "To

bring the interaction up to date, the warring parts

must confront each other, the struggle must be

expressed and articulated." Encouraging contact between the parts and acceptance of both

sides appears to be an important component of

helping the person to encompass the paradox of

opposites.

METHOD

If affective tasks, to which different clients

repeatedly seek resolution in therapy, can be

identified then these client task performances

can be studied as phenomena in their own right,

in order to reveal the structures underlying the

affective problem solving strategies. The 'split,'

as defined (Greenberg, 1979), possesses qualities of an affective task. It has a stable structure

and it occurs repeatedly within and across clients. In addition, clients experience the splits as

problems to be solved which constantly 'nag' at

them and demand attention until they are resolved.

The approach used here for the intensive

analysis of client performances on this task is a

form of task analysis developed for the study of

psychotherapeutic events (Greenberg, 1976).

Because of the many variables in a problem

solving event of this nature and because so much

goes on in any single problem solving encounter,

experiments of the classical sort are only rarely

useful for studying this type of phenomenon.

What is important is to collect enough data about

each individual subject and his/her performance

in a particular task in order to be able to identify

his/her method of resolving the task. Task

analysis requires the identification of the sequential stages through which a person progresses in

order to reach some objective. In general, task

analysis involves three components: identifying

and describing the task to be performed (the

split), breaking down of the task instructions so

that each item of the instruction conveys a separate and unique message (the two chair operation), and describing the actual moment by

moment performances of the individual engaged

in the task.

The task performances presented in this paper

were collected from individuals of specified

characteristics who had participated in a study of

the specific process effects of different therapist

operations (Greenberg, 1976). The clients were

specified as good prognosis clients for client

centered therapy and were selected on the basis

of having at least six out of twenty focused voice

statements midway in an initial interview (Rice

& Wagstaff, 1967). In addition all had focusing

responses on the post-focusing questionnaire

(Gendlin et al., 1966). Three events were collected for each of three clients from therapy

sessions in which the therapists were trained in

the recognition of splits and in the 'two chair'

145

ANALYSIS OF RECURRING EVENTS

operation. An event consisted of three parts: a

client statement of the task, in this case the

'split'; the ongoing task instructions presented

by the therapist, in this case the 'two chair operation' ; and the ongoing client task performance to

some point of termination of this performance.

In each event, therefore, a good prognosis client

was engaged in attempting to resolve a' split'.

In the study of effects the 'two chair' operation

led to deeper levels of experiencing than did

empathic reflections when both were randomly

applied to naturally occurring 'splits' which

clients reported in therapy (Greenberg, 1976). In

addition, it was shown that for these clients there

was a significant increase in the depth of experiencing over time in the Gestalt event. Having

shown that something therapeutically significant

was consistently occurring within these Gestalt

events, it appeared that a more intensive analysis

should be undertaken to explore the phenomena

more deeply and it is this analysis that is presented here. In problem solving terms, therefore,

the attainment of high levels of experiencing

(five and above) on the split performance was

regarded as a global process indicator of problem

resolution or approaches thereto. Level five on

the experiencing scale requires that problems or

propositions about feelings and personal experiences are being dealt with in an exploratory and

elaborative way and level six that the content is

"a synthesis of readily accessible, newly recognized or more fully realized feelings and experiences to produce personally meaningful structures or to resolve issues" (Klein etal., 1969).

Voice Quality (Rice & Wagstaff, 1967) and

Depth of Experiencing (Klein et al., 1969) both

of which have been shown to be indices of productive therapeutic process were used to rate the

client performance in the events. The taped excerpts of each event were broken into two-minute

segments and all the segments were randomized.

Experiencing scores were obtained for each chair

in all the segments by two raters. Voice was rated

by statement for each two-minute segment and

the predominant voice quality for each chair in

all the segments was obtained. A client statement

was defined as anything the client said between

two therapist responses. Voice was rated by one

rater for two clients and a second rater for the

third client. In addition, for a reliability check,

each rater overlapped on one-third of the material for each client. The reliability on the experiencing rating ranged from .72 to .81 on the

Pearson product moment correlation coefficient

for the three clients. Cohen's kappa, a coefficient of interjudge agreement (Cohen, 1960)

on voice ratings was significant at the .01 level

for each of the three clients.

RESULTS

The concrete events were separated from the

stream of in-therapy performance so as to study

the client performance on each task. The goal

was to identify some repeatable regularities in

these performances that would aid in characterizing the nature of a resolution performance. The

hypotheses with which the data were approached

were not clearly articulated as is to be expected in

a task analytic approach (Newell & Simon,

1972; Pascual-Leone, 1976). The characteristics

of each chair on the Experiencing Scale and on

voice quality were scrutinized to see if anything

would be revealed concerning the process of

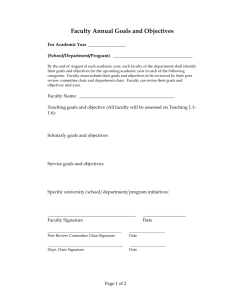

resolving splits. As the graphic representations

of the data were inspected (Figs. 1, 2 & 3) some

interesting differences in the two chairs on the

experiencing scale became apparent. Further intensive observation of the data from the three

clients led to the construction of the following

idealized model of the task performance.

On the experiencing scale, the two chairs can be regarded

as initially functioning as independent systems, i.e., the

two chairs can be characterized by different levels of

experiencing, one chair being consistently higher than the

other. At a certain point in the performance, a merging of

these two systems takes place by an increase in the level of

experiencing of the lower one. The two systems thereafter

proceed to task resolution at levels of experiencing which

do not distinguish them apart and which are collectively

higher than before. (Greenberg, 1976)

This pattern revealed itself consistently throughout the nine events from the three clients. In

addition, the following performance details appeared in the nine events:

1) Chair II, called "the experiencing chair,"

proceeded predominantly at level four or above.

2) Chair I, "the other chair," proceeded initially at lower levels and then, at a point called

the "merging point," increased to levels similar

to those of chair II.

3) In the latter part of the event, after the

increase in the "other chair" beyond level four,

i.e., after the merging point, both chairs tended

to attain levels of exp riencing higher than four.

This pattern occurred in all cases and the event

could therefore be characterized as consisting of

146

LESLIE S. GREENBERG

G0F3

6

•

Experiencing

_ Chair

5

4

Depth of

Experiencing

(P«ak

Values) 2

-

1

-

i

f/

/ /

I

i""O

\ /

Other Chair

Depth of

A'\ K

Experiencing 3 g

V

(Peak

-

Split

i

i

5

10

Merging

Point

i

15

i

20

Segments

Figure l(a)

Figure 2(a)

GOF 10

Experiencing Chair

4

Depth of

Experiencing 3

(Peak

Values)

2

1

ft

A

5 -

GAT 5

p

*

• r

Experiencing Cnair

Other Chair

-

Expariendng,

'

(Peak

Values!

,

Split

•

i

5

10

i

Merging

Point

v

•

i

Other Chair

Merging

Point

Split

20

Segments

30

Figure l(b)

35

Segments

Figure 2(b)

GAT 11

GOF 11

6

Experiencing

Chair^ p ^

5

,

4

Depth of

Experiencing 3

(Peak

Values) 2

1

V

»' \ »'

Depth o f 4

Experiencing

(Peak

*

Values

^ A ,v

/

Other C h a i r "

Merging Point

Split

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

15

Segments

Figure l(c)

20

Segments

Figure 2(c)

Clients Segment by Segment Depth of Experiencing for Each Chair for the Nine Events.

two phases, a pre-resolution phase, prior to the

increase in the other chair, and a resolution phase

in which both chairs tend to increase in depth of

experiencing.

The graphs in Figures 1, 2 and 3 indicate the

actual experiencing levels of the two chairs for

the three clients in each two chair event. In one

case, GOF 10, (Fig. 1 b) resolution is not as clear

as in the other cases because the other chair only

reaches 4.5 and the experiencing chair only

reaches 5. This event was terminated prematurely by the client because she had another appointment which she had to make. She reported

in the following interview that she had experienced discomfort all day and had only achieved a

sense of completion when she was able to attend

147

ANALYSIS OF RECURRING EVENTS

KAT 22

i

6r

5 "

A

Chair J{

Depth of 4 L f * ^ *

Experiencing

'

(Peak 3 • /

Values)

A

2 1 -

~<X><A

^oI

\ /

-/?

Other

Chair

SP"*

\J

a

Merging

Point

t

5

\f

10

15

20

25

Segments

Figure 3 (a)

KAT 3

I

61"

^ -

Depth of

Experiencinc

(Peak ' 3 r

Values!2 -

/

Experiencing / r ^ .

p.^ Chair Ji

^ 4 , / ' r ^ a 5 \ . ^•o-e£^

,ofr*rcrG£>.

Nio^K^r

^V^^?^

?!h;r

Chair

1 -

Split

Merging

Point

5

10

15

20

25

30

Segments

Figure 3(b)

KAT 7

,

Experiencing

Chair

r

. ^

i

\

/

tJ^

/YV

Depth of

/

\

Experiencing3

(Peak

Values) 2

1

/

V

'

Split Merging

| , I Point ,

5

10

Other Chair

|

15

!

20

t

25

Segments

F i g u r e 3(c)

to the problem prior to going to sleep. In the rest

of the cases, however, the higher levels reached

are all convincingly greater than or equal to five.

These levels on the Experiencing Scale clearly

represent conflict resolution or approaches to

resolution. The pattern of the two independent

systems which merge is shown clearly in all but

one of the nine events. In this exceptional case

(KAT 7), "the other chair," rather than proceeding initially at lower levels, immediately starts

off at level 5 and this event can be regarded as

proceeding directly to the resolution phase (i.e.,

level five or above on both chairs).

Excluding KAT 7, (Fig. 3c) which has no

experiencing before the merging, we see that

"the other chair" is always lower than "the

experiencing chair," in the preresolution phase.

The difference in mean levels of experiencing in

the preresolution phase is statistically significant

on a one-tailed test at the .05 level on the Mann

Whitney U test for both GOF and GAT. The

sample of two for KAT is too small to be tested

but it can be seen that both KAT events clearly

manifest the same phenomenon. Table 1 shows

the mean experiencing scores for the two phases

for each chair. Each client score was obtained by

averaging the mean phase score for the three

events. It can be seen that for each client both

chairs increase levels in the resolution phase.

The difference in preresolution and resolution

scores for each chair is statistically significant on

a one tailed test at the .05 level on the Mann

Whitney U test.

This data from experiencing ratings, therefore, demonstrate that in these events, the two

chairs follow different experiencing tracks until

such time as the lower chair increases in depth of

experiencing to levels comparable to that of the

experiencing chair. At this time, resolution is

approached and subsequently attained by the two

chairs both of which increase in level and tend to

reach levels of five and six on the experiencing

scale. The experiencing chair does, on some

occasions, measure higher levels before the resolution phase occurs, but the other chair never

reaches these before it peaks at level five or

above. This attainment of the "merging point"

by the "other chair'' can therefore be regarded as

a sufficient condition of resolution and a signal of

the resolution phase.

TABLE 1. Mean Experiencing in the Preresolution and Resolution Phases

Other Chair

Experiencing Chair

Client

Preresolution

Resolution

Mann Whitney U

GOF

GAT

KAT

GOF

GAT

KAT

3.2

3.5

3.7

4.2

4.5

4.2

4.5

4.5

4.6

5.2

4.9

5.1

0*

significant at the .05 level.

0*

148

LESLIE S. GREENBERG

TABLE 2. Proportion of Different Voices in the Two Chairs

Client Session

GOF

GAT

KAT

3

10

11

3

5

11

1

3

7

Sign

Chair 2 (Experiencing Chair)

Chair 1 (Other Chair)

X + L*

F+E*

X+L

F+E

.42

.38

.44

.7

.22

.43

.64

.73

.59

.58

.62

.56

.3

.8

.57

.27

.25

.42

.18

.2

.22

.6

.71

.5

.73

.75

.58

.82

.8

.78

.4

.29

.5

.36

.27

.41

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

* X external, L limited voice, Ffocused, E emotional voice.

The next step in this intensive analysis was to

see if the voice data in any way corroborated the

findings suggested by this model. If voice was

different in the two chairs, this would strengthen

the model that the two chairs act as independent

systems. Changes in voice after the merging

point would similarly strengthen the model that

there was some change phenomenon occurring

in the resolution phase. The graphs of the statement voice qualities used by the two chairs are

not presented due to their size and complexity. In

their place, summary statistics describing the data

are presented. In Table 2, the proportion of voice

statement groupings made in each chair are

shown. It shows the proportion of Limited plus

External statements and Focused plus Emotional

statements made in each chair. Limited and External are the voice styles that have been shown

to be indices of less productive therapy, while

Focused and Emotional have been shown to be

indices of productive psychotherapy as indicated

by the level of correlation between these styles

and successful outcome in client-centered therapy (Rice & Wagstaff, 1967; Rice etal., 1978).

It is seen that in each event, "the other chair"

uses more of the Limited plus External combination of voice qualities than does "the experiencing chair." A sign test applied to test

for a difference in the voice quality between

chairs shows that the proportions in the two

chairs are significantly different on a one tailed

test at the .01 level. The nine events are, however, not nine independent measures, as required

by the test; rather, there are three clusters of three

dependent measures. This violates the independence assumption of the test used. However, on

inspection it can be seen that the scores for each

event and for means of each client all show the

same effects, viz. the proportion of external plus

limited is always higher in the "other chair".

This indicates that the effect sh )wn by the test is

not due to bias from dependent subset of scores

but it an effect contributed to by all events and

clients. We may, therefore, view this finding

as indicating that the two chairs use different

voices.

The "other chair," therefore, uses more of a

combination of an energetic, outerdirected voice

(externahX) and an energyless, restricted voice

(limited:L) whereas the "experiencing chair"

uses more of a combination of a high energy

inner directed voice (focused:F) and a high enTABLE 3. Proportion of F+E Before and After

Merging in Chair 1 (Other Chair)

Client

GOF

GAT

KAT

Before

After

Sign

1

1

.55

+

+

3

10

11

.5

.6

.6

mean

.57

3

5

11

.25

.75

.43

mean

.47

1

3

7

.27

.125

.93

.38

.36

mean

.198

.37

.85

1

.9

.9

+

+

+

+

+

149

ANALYSIS OF RECURRING EVENTS

energy emotionally expressive voice (emotional :E). The "other chair" can be considered,

from this voice data, to be less involved and

making poor contact with itself or with the ' 'experiencing chair."

Although the "other chair" uses more poor

contact voice over the whole event, it was found

that the proportion of this voice used by this chair

was greater in the preresolution phase than in the

resolution phase. In other words, the proportion

of good contact voice in Chair I was higher in the

resolution phase. This is shown in Table 3 by the

proportion of good contact voice (F&E) being

greater in the resolution phase for seven of the

nine events. In GOF 11, there is a reversal, i.e.,

the proportion in preresolution is greater than in

the resolution phase and in KAT 7, as already

mentioned, there is no preresolution phase.

Using a sign test and regarding these as nine

independent events, the difference between preresolution phase and resolution phase is significantly different on a one-tailed test at the .05

level. From the means we see that the direction

of difference on the means is the same for each

client as in the majority of events. This again

gives an indication that the effect tested for on the

three clusters of three dependent measures was

contributed to by all of the clusters. This finding

therefore indicates that in' 'the other chair'' there

is a shift from the talking at, poor contact, voice

in the preresolution phase to the use of more

involved, good contact, voice in the resolution

phase.

In the case of GOF 11, where this was not the

case, the "other chair" made only five statements out of forty-two in the preresolution

phase, three of these five being focused. The

"other chair" is therefore seen to have spoken

very little in this phase. The proportion score for

focused voice is therefore based on a very small

sample and is not a highly stable estimate. The

score for "the other chair" in the resolution

phase by comparison is more stable, being based

on eleven statements out of a total of fifty-two

statements by both chairs.

The data from an inspection of voice and experiencing in conjunction at the merging point is

shown in Table 4. The middle column, 3, represents the voice quality of that segment which

accompanied the first increase or merging in

experience of the "other chair." This is the

"other chair's'' voice at the merging point or the

beginning of the resolution phase. On either side

TABLE 4. 'Other Chair'Voice Around Merging Point

Segments

1

2

At

Merging

3

Interview

3

GOF 10

11

GAT 3

5

11

KAT 1

3

7

X

X

X

X

L

L

X

X

-

X

F

F

X

F

L

X

X

X

F+E

F+E

F

F

F

F

E

F

F+E

Before

Merging

After

Merging

4

5

F

—

F

—

F

F

X

L

X

—

—

X

—

F

F

X

X

F

of this column are the voice qualities on the two

preceding segments (column 1 and 2) and the

two proceeding segments (column 4 and 5),

whenever these existed. It is seen that the voice

quality of "the other chair" at the beginning of

resolution is characteristically focused or emotional, what has been called good contact voice.

In six out of nine cases, the preceding two segments are either external or limited. In the other

three cases, the immediately preceding statement is focused but this is preceded by an external or limited voice segment. The ' 'other chair''

can therefore be regarded as having changed

from a poor contact to a good contact voice in the

immediate vicinity of the "merging point.'' This

is an interesting finding. The "other chair" is

sometimes focused before the merging point and

more often after the merging point, showing that

this voice is not in itself a sufficient condition for

resolution. Change to focused voice, however,

does appear to be a necessary condition for resolution. This change of voice by the other chair is,

therefore, an important therapeutic cue. When

this voice change in the "other chair" is accompanied by an increase in experiencing to the level

of the "experiencing chair," the task performance has entered the resolution phase.

DISCUSSION

What then emerges from this quantitative description of the actual performance? We find that

the two chairs can be thought of as independent

systems on voice and depth of experiencing and

that voice and depth of experiencing change in

such a manner as to imply two phases of the

150

LESLIE S. GREENBERG

event, a preresolution and a resolution phase. In

the preresolution phase, the "other chair" operates at levels of experience consistently below

level four and the "experiencing chair" consistently above level four. In the preresolution

phase, the ' 'other chair'' uses more poor contact

voice than in the resolution phase. We therefore

have a picture in the preresolution phase of the

"other chair" as uninvolved with its own experiencing and not in good contact with the "experiencing chair'', which is itself only moderately

involved and making some contact. The beginning of the resolution phase is marked by the

"other chair" simultaneously moving to a significantly deeper level of experiencing (above

4.5) and changing to a contactful voice. The

"experiencing chair" proceeds in resolution

phase at increased levels, around five and above

on the Experiencing Scale, while the other chair

now uses more contact voice and proceeds at

levels of experiencing clearly above level four.

The observed facts are in accord with the

idealized notion of a reconciliation of two parts

by integration. In the resolution phase, the

' 'other chair'' appears to soften; it becomes more

similar in style to the "experiencing chair", is

more involved and subjective, and describes its

own feelings more personally. There is a complementarity in the levels of depth of experiencing in the two chairs. The voice data suggests a

movement in the "other chair" from talking at

oneself to talking to oneself.

This perspective on the different nature of the

chairs can be used to help describe the unfolding

of the dialogue in productive therapeutic process. The "experiencing chair" represents the

experiencing part of the client which is similar to

the organism or the self of other experiential

therapies. Initially, when the dialogue is progressing well, this part engages in a process of

inner exploration and experiencing. The "other

chair", in contrast, is filled with the ego alien

parts of the personality and with the client's

attributions in the form of people or objects. The

person in this chair initially uses a more external

or lecturing voice and engages at low levels of

experiencing. The occupant of this chair is more

like the client's persecuting internal objects or

the outer world objects onto whom these have

been projected. The organism or the self in the

"experiencing chair" reacts or feels in the face

of the attitudes and actions of the occupant of the

"other chair.'' At some point in the dialogue the

"other chair" changes and becomes more similar to the "experiencing chair." The person in

the "other chair" shifts to higher levels of experience and more focused-expressive voice,

much as though he or she is becoming less critical, softer and more focused on his or her inner

experiencing in that chair.

These research results suggest that the therapeutic task is to initially promote experiencing

in the one chair and criticisms and projections

in the other chair. The knowledge of what good

'split' resolution performances look like provides therapists with a 'road map' of the territory which enables them to guide clients who

are losing their way. Being alert to any change in

tone and quality in the way the person relates to

themselves from the "other chair" can greatly

enhance the probability of facilitating split resolutions. The slightest indication of the other chair

softening or turning in on its own experience is

then promoted by the therapist in order to aid

integration.

The softening of the harsh internal critic appears to allow the experiencing in the "other

chair" to emerge and a constructive interchange

between alienated parts of the self to follow. The

process is similar to interpersonal conflict resolution in which the two parties initially quarrel but

then when the blamer takes a different stance in

the interaction and expresses some of what is

happening inside him or her the victim of the

attack is more able to listen to the other person.

Intrapsychic resolution similarly seems to require a change in stance by the internal blamer

followed by a process of mutual listening between parts of the self. Listening to oneself or

accepting oneself in order to resolve splits seems

to occur in a number of different ways. First, in

the experiencing chair the person must fully experience and accept the unaccepted or hidden

aspects of the self. Second the harsh critic, in

order to take a different stance, must accept,

listen to, or contact the feelings and fears underlying its criticism. By so doing a softening of the

criticism and a feeling of understanding and

compassion for the self occurs. Third, from the

base of self acceptance and self appreciation

established by the above processes, the two

chairs can then listen to each other or negotiate to

form a creative resolution between the parts.

Examination of the content of the dialogues in

the events studied show the shifts in the "other

chair" seemed to occur by a softening and a

151

ANALYSIS OF RECURRING EVENTS

greater sense of self acceptance. In the events

collected, the "other chair," at the merging

point, contained either another person or a part of

the self. Excerpts from GAT 3, a dialogue in

which a projected parent is the part in the ' 'other

chair," is given below to show the nature of the

shift at the merging point.

Preresolution phase

Other:

Do you want to go to hell? You must

want to —couldn't you even do it just for

us. What can I do—how can I be your

mother and have such a daughter?

Experiencing: I want you to love me because of who I

am / T say this again / Love me because

of who I am. What do you mean by that

she would say / T and what do you say?

I feel no guilt for the way I have lived.

I have made mistakes but I feel positive

about my life in the last few years. You

feel negative that they are lost years. You

have not believed me in the past which

has been really hard for me (soft voice).

T:

Exp:

T:

Exp:

T:

Exp:

Merging Point

Exp:

T:

Other:

T:

Other:

T:

Exp:

You see me through your eyes and according to your rules.

Come over here. How do you see her?

Be those eyes. What do you see over

there?

I see a sad girl, (focused voice)

So tell her this.

I see a lonely girl, you've had sex with all

sorts of men. I don't know how you could

be happy. I feel sad when I see you unhappy. I want to do something but I don't

know what to do. I want to see you make

a decision on what to do next, a good decision. Then I would say . . . (focused

voice)

Change

That's right—it took me years and years

to actually make a good decision as to

what to do next because I was floundering

the whole time trying to bring together

in a whole person the person who was

struggling between two ideas, I don't

know what to call it, you represented the

one commitment and what made it hard

for me was the emotional bond that you

loved me and required this of me . . .

I had no time for anything else. I had

no time to become, to make any sound

decisions career wise, marriage wise,

barely friend wise. I had no time for anything (cries) but untangling.

Resolution Phase

Exp:

I'm sad that I had to spend so much time

untangling. That's what I'm sad about

T:

and I'm actually pretty good these days

and I'm still a little lost but I'm really enjoying finding my way. I'm really enjoying i t . . . it's not a bad thing at all. I think

that coming to university has given me a

chance to enjoy finding my way, given

me some time to look around and prepare

myself.

So what's happening now—how are you

feeling?

I'm . . . I don't know what I'm feeling.

I don't. . .

Check out inside — what's happening?

I remember—I'm feeling very . . . as

soon as I explained how I'm enjoying

finding my way now I forget I had . . .

I felt really good because it's true. My

life isn't any easier than it ever was but

I'm enjoying it.

I heard some real life and energy come

into that. . . That's when you're in touch

with that. . . then you feel strong.

Yeah, it's very true I don't feel about myself the way my family feels toward me

regarding my past which has been really

patchy what would you call it checkered.

It really has been . . . I ' v e done a lot of

things and tried many things that to an

outsider might appear one way or the

other very good or very bad but within

myself I know that I was always, true, I

might as well tell her that.

Uhhum.

In this example, the client moves from criticizing and derogating herself in the "other chair"

in the preresolution phase to feeling compassion

("I see a sad girl") and personalizing her experience in this chair ("I feel sad," "I want to do

something") at the merging point. A resolution

then emerges in the "experiencing chair," "I'm

finding my way," etc. The key element of

change occurs when the harsh critic takes a different stance, stops blaming and begins to feel a

form of empathy or compassion toward the self.

Rather than being scolding, this 'other' part of

the self begins to talk about its own experiences,

wants and fears, and the emphasis shifts toward a

dialogue of mutual understanding. A content

analysis of the transcripts thus adds weight to the

model constructed from the voice and experiencing data.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates the power of intensive analysis in psychotherapy research. It enables the 'clinician researcher' to identify and

rigorously describe phenomena which exist but

which have yet to be rendered visible in their

LESLIE S. GREENBERG

152

essential form. Intensive analysis of these Gestalt events has allowed a detailed elaboration of

some of the subtleties of the therapeutic process

and by so doing has opened new avenues for

clinical practice and research. These results can

enhance therapeutic functioning by alerting the

therapist to the independent systems in the

chairs, to shifts in the "other chair" and to

merging between the chairs. In addition, the

isolation of this client task and the discovery of

repeatable regularities in the task performances

allows us to begin to seek answers to questions

such as, what are the cognitive, attentional and

affective mechanisms associau d with the shift at

the merging point?

REFERENCES

BAKAN, D. The duality of human existence. New York:

Jossey-Bass, 1966.

COHEN, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales.

Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37-46,

1960.

GENDLIN, E. et al. Focusing ability in psychotherapy, personality and creativity. In J. Shlein (Ed.), Research in

Psychotherapy. Vol. Ill: A.P.A., 1968, pp. 217-328.

GREENBERG, L. A task analytic approach to the events of

psychotherapy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, York

University, Toronto, 1976.

GREENBERG, L. Resolving splits: Use of the two-chair technique. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice,

16,316-324, 1979.

JUNG, C. G. The collected works of C. G. Jung. G. Adler,

M. Fordham and H. Read (Eds.). New York: Bellingen

Foundation, 1966.

KLEIN, M., MATHIEU, P., KIESLER, D. & GENDLIN, E. The

experiencing scale. Madison, Wise: Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute, 1969.

NEWELL, A. & SIMON, H. Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972.

PASCUAL-LEONE, J. Metasubjective problems of constructive cognition: Forms of knowing and their psychological

mechanisms. Canadian Psychological Review, 17, 110125,1976.

PERLS, F. Gestalt therapy and human potentialities, Esalen

Paper, No. 1,1965.

PERLS, F. Gestalt therapy. Lafayette, Calif.: Real People

Press, 1969.

PERLS, F. Four lectures. In J. Fagan & I. Shepherd (Eds.),

Gestalt Therapy Now. Palo Alto: Science and Behavior

Books, 1970.

POLSTER, E. & POLSTER, M. Therapy without resistance. In

A. Burton (Ed.), Gestalt Therapy in What Makes Behaviour Change Possible, Brunner/Mazel, 1976.

RANK, O. Will therapy and truth and reality. New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 1945.

RICE, L. & WAGSTAFF, A. Client voice quality and expressive style as indices of productive psychotherapy. Journal

of Consulting Psychology, 31, 557-563, 1967.

RICE, L.,

KOKE, C ,

GREENBERG, L. & WAGSTAFF, A.

Voice quality training manual. Counselling & Development Centre, York University, Toronto, 1978.