Group Theory. Symmetry Groups of Molecules

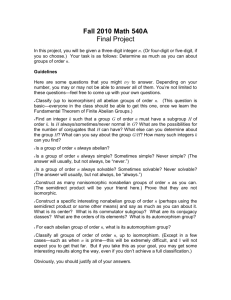

advertisement

Math Methods I

Lia Vas

Groups

Introduction of Groups via Symmetry Groups of Molecules

Determination of the structure of molecules is one of many examples of the use of the group

theory. Electronic structure of a molecule can be determined via its geometric structure. In this

case, one consider the symmetry of a molecule since it reveals information about its properties (i.e.,

structure, spectra, polarity, chirality, etc).

The following diagram represents the above steps.

Geometry of a molecule

−→

Symmetry Group

↑

Structural Properties

↓

←−

Group Representation

Symmetry of a molecule is characterized by the fact that it is possible (theoretically) to carry out

operations which will interchange the position of some (or all atoms) and result in the arrangement

of atoms that is indistinguishable from the initial arrangements. Thus, the operations we shall

consider are exactly those that we can apply on a model of a molecule so that the resulting molecule

appears the same as the original one.

Operations are:

- rotations - physically possible, are called proper rotations.

- reflections with the respect to a mirror plane or to the center of symmetry - physically

impossible, are called improper rotations.

These set of all those operations is called a group of symmetries. The features of such group

that we are interested in is that

1) a composite of two operation from the group is again an operation from the group.

Let us denote the composite of two operations a and b with a · b or, shorter ab. With this notation,

the operations a, b and c of a symmetry group satisfy the associativity law:

2) a(bc) = (ab)c

There is a distinct element of every group of symmetry, called identity element and denoted by

1 which corresponds of operation of not moving molecule at all (equivalently, rotation for 0 degrees).

Thus, the identity element 1 satisfies

3) a1 = 1a = a for every operation a.

1

Finally, for every operation a defines the corresponding operation, denoted a−1 reversing the

effect of a. For example, if a is a rotation for α degrees, then a−1 is the rotation for α degrees in the

opposite direction (equivalently, rotation for −α degrees). Thus, the composition of a and a−1 is the

identity operation.

4) aa−1 = a−1 a = 1.

These four laws are independent of the chemical setting and, as it turned out, there are many

other situations in which the set of elements considered satisfies these four laws. So, it turned out

that the study of any structure satisfying the above four laws, a group, was of interest for many

disciplines. The study of group became known as the group theory.

History

Historically, group was not defined in the context of chemistry and symmetries of molecules.

There are three historical roots of group theory:

1) the theory of algebraic equations, 2) number

theory and 3) geometry. Euler, Gauss, Lagrange,

Abel and Galois were early researchers in the field

of group theory. Galois is honored as the first

mathematician linking group theory and field theory, with the theory that is now called Galois theory.

Galois remains an intriguing and unique person in the history of mathematics. The footnote

contains some more information from wikipedia.org. 1

1

Évariste Galois (October 25, 1811 May 31, 1832) was a French mathematician born in Bourg-la-Reine. He was a

mathematical child prodigy. While still in his teens, he was able to determine a necessary and sufficient condition

for a polynomial to be solvable by radicals, thereby solving a long-standing problem. His work laid the fundamental

foundations for Galois theory, a major branch of abstract algebra, and the subfield of Galois connections. He was the

first to use the word ”group” as a technical term in mathematics to represent a group of permutations. He died in a

duel at the age of twenty.

In 1828 he attempted the entrance exam to École Polytechnique, without the usual preparation in mathematics,

and failed. He failed yet again on the second, final attempt the next year. It is undisputed that Galois was more

than qualified; however, accounts differ on why he failed. The legend holds that he thought the exercise proposed to

him by the examiner to be of no interest, and, in exasperation, he threw the rag used to clean up chalk marks on the

blackboard at the examiner’s head. More plausible accounts state that Galois refused to justify his statements and

answer the examiner’s questions. Galois’s behavior was perhaps influenced by the recent suicide of his father.

His memoir on equation theory would be submitted several times but was never published in his lifetime, due to

various events. Initially he sent it to Cauchy, who told him his work overlapped with recent work of Abel. Galois

revised his memoir and sent it to Fourier in early 1830, upon the advice of Cauchy, to be considered for the Grand

Prix of the Academy. Unfortunately, Fourier died soon after, and the memoir was lost. The prize would be awarded

that year to Abel posthumously and also to Jacobi.

Despite the lost memoir, Galois published three papers that year, which laid the foundations for Galois Theory.

Galois was a staunch Republican, famous for having toasted Louis-Philippe with a dagger above his cup, which

leads some to believe that his death in a duel was set up by the secret police. He was jailed for attending a Bastille

2

Mathematical Definition of a Group

Let us give a precise mathematical definition of a group.

Definition. A group is a nonempty set G with operation · such that

A1 The result of operation applied to two elements of G is again an element of G (i.e. if a and b

are in G, a · b is also in G). In this case we say that the operation · is closed).

A2 Associativity holds: (a · b) · c = a · (b · c) Operation with this property is said to be associative.

A3 There is identity element 1 so that a · 1 = 1 · a = a for every element a.

A4 Every element a has the inverse a−1 (i.e. a · a−1 = a−1 · a = 1).

As before, we will shorten the notation a · b and write just ab. Also, if G with operation · is a

group, we will say that G is a group under operation ·.

Note that A4 implies the cancellation law: ab = ac or ba = ca imply b = c.

This can be verified by multiplying ab = ac from the left with a−1 to get that b = c. Similarly,

multiply ba = ca from the right with a−1 to get b = c.

Examples.

1. Real numbers without 0 under multiplications. The identity element is 1 and 1/a is the inverse

of a. Note that rational or complex numbers without 0 under multiplication also form groups.

Integers without 0 under multiplication, however, are not a group as A4 is not satisfied for

every integer a. Give an example of this.

Note also that we have to throw out 0 as all real numbers under multiplication are not a group.

Indeed, the element 0 does not have an inverse as there is no solution of the equation 0x = 1

(i.e. we cannot divide with 0).

2. Real numbers under addition. This is an important example because it tells us that the notation

for operation in specific group might be denoted differently that the one used in the general

definition. Note that in this example the identity element is 0 and the inverse of a is −a. The

essential fact is that the laws A1–A4 remain to hold regardless of the change in notation:

A1 a and b are real numbers, a + b is also a real number.

A2 (a + b) + c = a + (b + c).

Day protest in 1831, and was released only 2 days before his death.

The night before the duel, supposedly fought in order to defend the honor of a woman, he was so convinced of

his impending death that he stayed up all night writing letters to his Republican friends and composing what would

become his mathematical testament. Hermann Weyl, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, said of

this testament, ”This letter, if judged by the novelty and profundity of ideas it contains, is perhaps the most substantial

piece of writing in the whole literature of mankind.” In his final papers he outlined the rough edges of some work he

had been doing in analysis and annotated a copy of the manuscript submitted to the academy and other papers. On

the 30th of May 1832, early in the morning, he was shot in the abdomen and died the following day at ten in the

Cochin hospital (probably of peritonitis) after refusing the offices of a priest. He was 20 years old. His last words to

his brother Alfred were: ”Don’t cry, Alfred! I need all my courage to die at twenty.”

Galois’ mathematical contributions were finally fully published in 1843 when Liouville reviewed his manuscript and

declared that he had indeed solved the problem first proposed and also solved by Abel. The manuscript was finally

published in the October-November 1846.

3

A3 0 is the identity element and a + 0 = 0 + a = a for every element a.

A4 Every element a has the inverse −a and a + (−a) = (−a) + a = 0.

Note that integer, rational or complex numbers are also a group under addition. Nonnegative

integers are not a group under addition since A4 does not hold.

3. Vectors in plane under addition.

4. Set of invertible real valued functions under composition of functions. Note that this is the

first example of a group in which the commutativity law (ab = ba) does not hold. Recall many

examples of functions for which the composition is not commutative. For example f (x) = 2x

and g(x) = x − 1. Then f (g(x)) = 2x − 2 and g(f (x)) = 2x − 1.

5. Linear Algebra examples. Real valued matrices form a group under addition. Invertible real

valued matrices form a group under matrix multiplication.

6. Note that all of the above examples were examples of groups with infinitely many elements.

Infinite groups appear in chemistry as well. They are used in the description of translational

symmetry of some crystal lattices. Examples of finite groups will follow shortly.

7. Non-examples. At this point, it might be useful to present some ”non-examples”, i.e. examples of sets that fail some of the rules A1–A4.

We have already seen that the nonnegative integers do not satisfy A4 under addition.

Positive integers do not satisfy even A3 under addition.

The set of integers is not associative under subtraction since

a − (b − c) = a − b + c 6= a − b − c = (a − b) − c

so A2 fails.

The set of positive integers is not closed under subtraction so A1 fails.

Why A1–A4?

Let us expand on the meaning of the rules A1–A4. A1 is necessary to avoid situations as in the

example with positive integers and subtraction.

The rule A2 let us not use the parenthesis as we can denote (ab)c = a(bc) simply by abc. This

rule also enables us to write long formulas like a(b((cd)e)(f g)) simply as abcdef g.

The rules A3 and A4 enable us to ”divide” i.e. these rules guarantees that the equations ax = b

and ya = b have solutions in G for all a and b from G. This is because we can take x to be a−1 b and

y to be ba−1 .

Conversely, a set G satisfying A1, A2 and the rule

D For all a and b from G, the equations ax = b and xa = b have unique solutions in G.

satisfies the rules A3 and A4 as well. This is because

1. 1 is the solution of the equation ax = a for an element a. You still have to show that ax = a

and bx = b produce the same solution for different a and b.

4

2. For every element a, the solution of the equation ax = 1 is a−1 . You still have to show that a−1

is also solution of ya = 1.

The above gives an outline of the proof of the following proposition.

Proposition. A nonempty set G is a group (i.e. satisfies A1–A4) if and only if it satisfies A1,

A2 and D.

Cayley Tables

The previous proposition provides a very easy way to check if a given finite set of elements and

an operation on them form a group or not. A finite set of element and an operation on them is

frequently given by a table illustrating the result of operation for each pair of elements. Such table

is called a Cayley table, named after the mathematician Arthur Cayley. It is a generalization of a

multiplication table (as used to teach school-children multiplication). It is a grid where rows and

columns are headed by the elements to multiply, and the entry in each cell is the product of the

column and row headings.

· a b c

a a b a

For example, following is a Cayley table on a set of three elements.

b c a b

c c c b

Let us look at the part of the table without column and row headings. Note that the first row

represents different results of the multiplication from the left with a. But in the first row, there is no

element c. That means that the equation ax = c has no solution. Hence, this table does not represent

a group. Similarly, note that in the first (non-headed) column, there is not element b present. As a

consequence, the equation ya = b has no solution.

From this example, we can conclude that a necessary condition for a Cayley table to represent a

group is that in every row and column each element appear at least once. If some elements appears

twice, then the cancellation law does not hold so

1) Every element appears exactly once in every row and every column.

Also,

2) There has to be an element such that the row and column determined by that elements are the

same as the heading row and column. In this case, that element is the identity.

If a Cayley table of a set G satisfies rules 1 and 2, then G satisfies A1, A3, A4. Associativity

law A2 is hard to check using Cayley table. Checking associativity boils down to checking all the

possible triples of elements a, b, c satisfy the rule (ab)c = a(bc).

· a b c

a a b c

An example of a Cayley table of a set of three elements that is a group is

b b c a

c c a b

In this example, a is the identity, and b and c are mutually inverse to each other.

A group is called abelian if it satisfies the commutative law

ab = ba.

We have seen many examples of abelian groups and some examples of groups that are not abelian. If

a group is finite, one can easily check if it is abelian or not using its Cayley table: you simply check

5

if the table is symmetric with respect to the main diagonal. Using this rule, we conclude that the

group with the above Cayley table is abelian.

Groups with 2 elements. Let us use Cayley table to try to describe all the groups with 2

elements a, b. As one of them has to be identity, let us take a = 1 so ab = ba = b and aa = a. As the

· a b

result of bb has to be different than ba, bb has to be a. Hence, a a b is the resulting table.

b b a

Note that this is the only possible way we could fill the table given the condition that a is the

identity. If we chose b to be identity and rearrange the heading column so that the identity is the

· b a

first element of the heading column or row, we would end up with the following table.

b b a

a a b

This table describes the same structure of the group, the only difference is the names we assigned

to the elements. Having the correspondence a → b and b → a from first table to the second, we

would end up with the same group. The above correspondence is an example of group isomorphism.

The two groups are isomorphic if you can relabel the elements of one group then producing the

other. As isomorphic groups are intrinsically the same, mathematicians are often considering them

as one. One of the most important questions in group theory is to determine if a given two groups

are isomorphic or not. Note that some chemists refer to isomorphic groups as isomorphous groups

(e.g. in Kettle’s Symmetry and Structure).

A group isomorphism preserves all the group properties. For example, if one group is abelian

and the other is not, then they cannot be isomorphic. This gives you useful criterion for determining

that two groups are not isomorphic.

• To demonstrate that two groups are isomorphic, you can match their elements and show

that the matching preserves the Cayley table. We shall see later that two groups having the

same presentation also shows their isomorphism.

• To demonstrate that two groups are not isomorphic, you can note that they do not share

the same properties. For example, having different number of elements, one being abelian and

the other not, elements having different order etc.

We present further examples of groups isomorphic to the groups above. Let us consider, the

group of two integers 1 and -1 under the multiplication. This is another group isomorphic to the

above group with elements a and b. Yet another example is the group of remainders when dividing

with 2. Note that when any integer is divided by 2, the remainder is either 0 or 1.

Thus 1 + 0 = 0 + 1 = 1, 0 + 0 = 0. As 1+1=2

and 2 has remainder 0 when divided by 2, we have

1+1=0. Hence the following table represents this

group.

+ 0 1

0 0 1

1 1 0

This is another example of a group isomorphic with the above three groups with two elements

we considered. In mathematics, this group is denoted by Z2 . In chemistry, the notation C2 is used.

We concluded that all the groups with two elements have to be isomorphic to each other. We

can take C2 to be the representative of all the groups with two elements.

Groups of 3 elements.

6

Let us consider the groups of three elements.

As one of the three elements has to be identity,

let us denote elements by 1, a and b and let us

start filling the Cayley table.

·

1

a

b

1 a b

1 a b

a

b

If we put 1 in the first empty place in the second row of the table (again the rows are counted

without the heading elements), then we will have to put b in the last free place in the second row if

we do not want to violate the rule for each element in each row appearing exactly once. But then b

will appear twice in the last column, so we cannot fill the table this way.

This mean that the second row has to be a, b, 1

and this uniquely determines the last row and

hence the entire table. So, the following is the

complete Cayley table.

·

1

a

b

1

1

a

b

a

a

b

1

b

b

1

a

Note that this group is isomorphic to the group from example on page 6. Another group of three

elements can be obtained considering remainders when dividing with 3, similarly as in the example

with C2 . Any integer has a remainder when divided by 3 either 0, 1 or 2. So, we take these three

elements to be the elements of the group.

To obtain the Cayley table, note that the elements add considering the remainder of their sum

when dividing by 3. For example 2+2=4 which

has remainder 1 when divided by 3, so 2+2=1.

+

0

1

2

0

0

1

2

1

1

2

0

2

2

0

1

Note that the identity element here is 0, not 1 since we are using the additive, not multiplicative notation. Analogously to the reminders when dividing by 2, this group is denoted by Z3 (in

mathematics) or C3 (in chemistry).

As we have seen, there is just one (isomorphism type of a) group with three elements. As the

next section will show, for groups with more elements, the situation can be different.

Groups of 4 elements. As we will see, the situation when describing the groups of 4 elements is more complex. So, before considering the groups with 4 elements, consider some additional

observations that will help us create different Cayley tables.

The rule A4 has the consequence that ab = 1 implies ba = 1.

If a2 = 1 then ab 6= 1 6= ba for all b 6= a. This means that each non-identity element is either its

own inverse or it pairs up with another element which is its unique inverse creating the two possible

situations:

· ... a ... b ...

...

a

1

...

b

1

...

· ... a ...

...

a

1

...

7

When trying to classify the finite groups using the Cayley table, it is possible to rearrange the

order of the labeled columns such that the first columns to appear, reading from left to right, are

those representing self-inverse elements, starting first with the identity element which is always a

self-inverse. After all the columns of self-inverses should follow the columns representing pairs of

inverses: each pair of inverses should be represented by a pair of adjacent columns. Following this

rule, in the case of groups with four elements 1, a, b, and c we have two possibilities.

·

1

a

b

c

·

1

a

b

c

1 a b c

1 a b c

a 1

b

1

c

1

1 a b c

1 a b c

a 1

b

1

c

1

These resulting arrangement of identity elements are called the identity skeletons of the Cayley

table. It is usually useful to write the identity skeleton when filling the Cayley table of a group.

Groups with different identity skeletons cannot be isomorphic. An identity skeleton boils down

simply to numbers of self-inverses versus number of inverse pairs.

Since the remainder of these two tables can be filled on unique way, we obtained that there are

exactly two classes of non-isomorphic groups with four elements and that they are

·

1

a

b

c

1

1

a

b

c

a

a

1

c

b

b

b

c

1

a

·

1

a

b

c

c

c

b

a

1

1

1

a

b

c

a

a

1

c

b

b

b

c

a

1

c

c

b

1

a

The first one is the Cartesian product C2 × C2 (set of ordered pairs of elements from C2 ). The

correspondence here is

1 7→ (0, 0),

a 7→ (1, 0),

b 7→ (0, 1) and c 7→ (1, 1).

The second table is isomorphic to the group C4 , the group of remainders when dividing with 4.

The correspondence here is

1 7→ 0, a 7→ 2, b →

7 1 and c 7→ 3.

Classes of Groups

There are many different classes of groups. Classifying different groups is one of the largest

problems of group theory. We will mention some important classes of groups.

Cyclic groups Cn . Cyclic groups are those that are generated with a single element. This

means that every non-identity element of a cyclic group can be obtained from that single element.

For example, the set of integers under addition is generated by 1. It turns out that all the infinite

cyclic groups are isomorphic to this one.

Using analogous notation as for C2 and C3 , let

us define Cn to be the group of remainders when

dividing by n. For example, C5 has the following

Cayley table:

8

+

0

1

2

3

4

0

0

1

2

3

4

1

1

2

3

4

0

2

2

3

4

0

1

3

3

4

0

1

2

4

4

0

1

2

3

All these groups are cyclic since the element 1 generates the entire group. Even more is true: every

cyclic group with n elements is isomorphic to Cn . We can illustrate this by the following example.

Consider the cyclic group of 5 elements. Since table of this group.

· 1 a

the group is cyclic, there is an element a that

generates it. In this case, the group elements are

1 1 a

2 3 4

5

1, a, a , a , a . The element a has to be 1 since

a a a2

the group would have more than 5 elements otha2 a2 a3

erwise. In this case, the following is the Cayley

a3 a3 a4

a4 a4 1

a2

a2

a3

a4

1

a

a3

a3

a4

1

a

a2

a4

a4

1

a

a2

a3

So, we can see that the above two Cayley tables are isomorphic by

0 7→ 1, 1 7→ a,

2 7→ a2 , 3 7→ a3 and 4 7→ a4 .

One can also see that every cyclic group is abelian.

Order of group. Order of group element. If a group G has n elements, we say it has order

n. If an element a is such that an = 1 and am =6= 1 for any m < n, we say that a has order n.

Presentation of Cyclic Groups. Consider the cyclic group of order n. If we denote the

generator by a, the group is uniquely determined by the relation an = 1. For example, if n = 5, we

can determine the above Cayley table simply knowing (1) that there is just one generator a, (2) that

this generator satisfies the equation a5 = 1. Analogously, any group can be determined by the list of

generators and the list of relations these generators satisfy. This is called the group presentation.

In a group presentation, the generators are listed followed by relations among them. For example,

the group presentation of the cyclic group of order n is

ha|an = 1i.

As the infinite cyclic group does not have any relations on its generator, the presentation is hai. This

group is isomorphic to the group of integers under addition via the isomorphism n → an .

Dihedral Group Dn and its presentation. Dihedral groups are groups of symmetries of

regular polygons. The group of symmetries of a regular polygon of n sides is denoted by Dn .

For example, let us consider a square. The

symmetries of a square are: rotations for 0, 90,

180 and 270 degrees, reflections with respect to

diagonals and x and y axes (if the square is centered at the origin so that the sides are parallel to

x or y axis). Clearly, the rotation for 0 degrees is

the identity, let us denote it with 1. If we denote

the rotation for 90 degrees by a, then the rotations by 180 and 270 degrees are a2 and a3 and

then a4 = 1.

Let us denote the reflection with respect to y-axis by b. Then b2 = 1, ab is reflection with respect

to the main diagonal, a2 b is reflection with respect to x-axis and a3 b is reflection with respect to the

non-main diagonal. So, all the symmetries of the square can be written via a and b. This means

that a and b are generators of D4 . Also, note that ba = a3 b.

9

Since ba is the reflection with respect to non- Using this presentation, we

main diagonal, it is different than ab, the reflec·

1

a a2 a3

tion with respect to main diagonal. So, D4 is not

1

1

a a2 a3

abelian.

a

a a2 a3

1

The equations a4 = 1, b2 = 1, and ba = a3 b on

a2 a2 a3

1

a

the generators a and b completely determine the

1

a a2

a3 a3

Cayley table of D4 . This means that the group

3

b

b a b a2 b ab

D4 is given by the presentation

ab ab b a3 b a2 b

a2 b a2 b ab b a3 b

4

2

3

ha, b|a = 1, b = 1, ba = a bi.

a3 b a3 b a2 b ab b

can fill the table.

b ab a2 b a3 b

b ab a2 b a3 b

ab a2 b a3 b b

a2 b a3 b b ab

a3 b b ab a2 b

1 a3 a2 a

a

1 a3 a2

a2 a

1 a3

3

2

a

a

a

1

Every dihedral group has analogous presentation. The group Dn has two generators a, the

rotation for 360/n degrees, and b, reflection with respect to y axis, and it satisfies an = 1, b2 = 1,

ba = an−1 b. Thus,

Dn = ha, b|an = 1, b2 = 1, ba = an−1 bi.

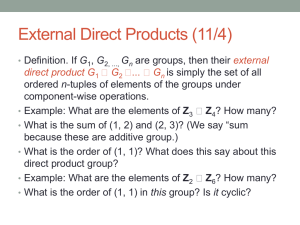

Direct Product of Groups and their presentations. As the plane of real numbers is obtained

by considering ordered pairs of real numbers, a new group can be obtained by considering ordered

pairs of elements from two other groups. More precisely, if G1 and G2 are two groups, we can define

a new group G = G1 × G2 by considering the elements of G to be the ordered pairs (g1 , g2 ) where g1

is from G1 and g2 is from G2 . The operation in G is defined on the following way:

(g1 , g2 ) · (h1 , h2 ) = (g1 h1 , g2 h2 ).

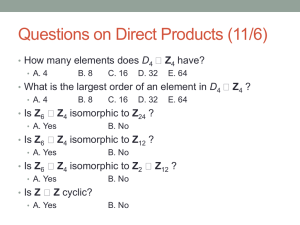

If G1 has n elements and G2 has m elements, then G1 × G2 has mn elements.

If we know the presentations of G1 and G2 , the presentation of G1 ×G2 is obtained on the following

way

- generators are all of G1 and of G2

- the relations are all of G1 , G2 plus relations that assert that the generators of G1 commute

with the generators of G2

Example 1. The group C3 × C2 = ha|a3 = 1i × hb|b2 = 1i has the presentation

ha, b|a3 = b2 = 1, ab = bai.

So, this group has 6 elements 1, a, a3 , b, ab, a2 b as any other ”word” in two letters a and b can be

written as one of those 6 using the above relations.

Example 2. As another example, let us look at D3 × C2 . As D3 = ha, b|an = b2 = 1ba = a2 bi

and C2 = hc|c2 = 1i, the presentation of D3 × C2 is

ha, b, c|an = b2 = c2 = 1, ba = a2 b, ac = ca, bc = cbi.

So, this group has 12 elements

1, a, a2 , b, ab, a2 b

c, ac, a2 c, bc, abc, a2 bc

10

as any other ”word” in three letters a, b and c can be written as one of those 12 using the above

relations.

If any of the groups G1 or G2 is infinite, then G1 × G2 is infinite. We have seen examples of direct

product of groups. The first example was the group of vectors in real plane under addition. This

group is denoted by R2 and it is the direct product of real numbers R under addition with itself.

We can consider a direct product of R2 and R (denoted by R3 ). This is the real three dimensional

space. It is a group under addition. On page 9, we have seen one example of a direct product of

finite groups when considering a group of four elements C2 × C2 .

Direct product of Cyclic Groups. Let us consider the group C3 × C2 with presentation

ha, b|a3 = b2 = 1, ab = bai from Example 1 and compare it with the cyclic group of order 6 C6 =

hc|c6 = 1i. We claim that these two groups are isomorphic.

To note that, note that the element ab has order 6. Indeed

(ab)0

1

(ab)1

ab

(ab)2

a2

(ab)3

b

(ab)4

a

(ab)5

a2 b

(ab)6

1

Then note that this can be matched with the powers of element c in C6 = hc|c6 = 1i.

(ab)0

1

1

(ab)1

ab

c

(ab)2

a2

c2

(ab)3

b

c3

(ab)4

a

c4

(ab)5

a2 b

c5

(ab)6

1

c6

Comparing the Cayley’s tables shows that the pairing of the elements above really is the isomorphism

of the two groups.

b

a a2 b

C3 × C2 1 ab a2

1

1 ab a2

b

a a2 b

2

ab a

b

a a2 b 1

ab

a2

a2

b

a a2 b 1 ab

b

a a2 b 1 ab a2

b

a

a a2 b 1 ab a2

b

2

2

2

ab

a b 1 ab a

b

a

C6

1

c

c2

c3

c4

c5

1

1

c

c2

c3

c4

c5

c

c

c2

c3

c4

c5

1

c2

c2

c3

c4

c5

1

c

c3

c3

c4

c5

1

c

c2

c4

c4

c5

1

c

c2

c3

c5

c5

1

c

c2

c3

c4

On the other hand, the groups C2 × C2 and C4 are not isomorphic. One way to see that is by

noting that the square of all elements in C2 × C2 is the identity while the square of the generator of

C4 is not identity.

Another way to see that C2 × C2 and C4 are not isomorphic is to compare the identity skeletons

of the Cayley’s tables.

C 4 1 c c 2 c3

1 1 c c 2 c3

c c c 2 c3 1

c2 c2 c3 1 c

c3 c3 1 c c 2

C2 × C2 1 a b ab

1

1 a b ab

a

a 1 ab b

b

b ab 1 a

ab

ab b a 1

Our observations are just special cases of the following claim.

11

Cm × Cn is isomorphic to Cmn if and only if m and n are relatively prime

(i.e. the greatest common divisor of m and n is 1).

To prove this claim, you can argue as we did in two examples above:

• If m and n are relatively prime, the element ab will have order mn so you can define the

isomorphism by mapping ab 7→ c. Note that this determines the images of the rest of the

elements just like in the example with m = 3 and n = 2.

• If m and n have the largest common divisor d > 1, then the group Cm × Cn does not have

an element of order mn (that is, all its elements are of order smaller than mn). On the other

hand, the generator c of Cmn has the order mn.

This claim makes possible to determine all the isomorphism classes of abelian groups of certain

(finite) order. We illustrate that by the following example.

Example 3. Produce all isomorphism classes of abelian groups of order 24.

Solution. Write 24 as product of powers of prime numbers: 24 = 8 · 3 = 23 · 3. Since 2 and

3 are relatively prime, the group C3 can be combined with any group of C2 × C2 × C2 , C4 × C2 ,

or C8 , creating isomorphic pairs of groups. Any of these three groups, on the other hand, are not

isomorphic because the order of elements do not match. Thus, there are 3 non-isomorphic abelian

groups of order 24

1. C3 × C2 × C2 × C2

2. C3 × C4 × C2

3. C3 × C8 ∼

= C24

∼

= C6 × C2 × C2

∼

= C12 × C2

∼

= C6 × C4

As a large percentage of point groups encountered are cyclic, dihedral, product of two cyclic or

product of a cyclic and a dihedral, let us look more closely to those examples.

Group

Cyclic (order n)

Product of 2 cyclic

Dihedral

Product of Dn and Cm

notation

Cn

Cn × Cm

Dn

Dn × Cm

no. of el.

n

mn

2n

2nm

presentation

ha|an = 1i

n

ha, b|a = bm = 1, ba = abi

ha, b|an = b2 = 1, ba = an−1 bi

see below

Using the above analysis for getting a presentation of a product, the presentation of Dn × Cm , is

ha, b, c|an = b2 = cm = 1, ba = an−1 b, ca = ac, bc = cbi

We will be specially interested in the case when m = 2 both when considering Cn × Cm and

Dn × Cm .

We should also note the distinction between Cn × C2 and Dn . Both of these two groups have 2n

elements. They are not isomorphic as Cn × C2 is abelian, while Dn is not. This can be seen the best

when comparing their presentations

ha, b|an = b2 = 1, ba = abi and ha, b|an = b2 = 1, ba = an−1 bi.

12

4. Symmetric Groups. Let us consider a set {1, 2, 3}. Let us look at all the possible permutations of this set (i.e. one-to-one mappings of this set onto itself). As when the symmetries of

polygons were considered, the product of two such mappings is their composition. There are 6

such mappings mapping (1, 2, 3) to

(1, 2, 3), (1, 3, 2), (2, 1, 3), (2, 3, 1), (3, 1, 2), and (3, 2, 1).

This groups is called the symmetric group on 3 letters and is denoted by S3 . Analogously, the

permutations on n elements form a group denoted by Sn . Sn has n! elements.

Symmetric groups are especially important in group theory because of the Cayley’s theorem

stating that every group can be represented as a subgroup of some symmetric group.

There is another important class of groups called alternating groups An . They are related to

Sn . One of the presentations will focus on alternating groups An .

5. Symmetries of Platonic Solids: tetrahedral Td , octahedral Oh and icosahedral group Ih .

Platonic or regular solids are convex polyhedra with equivalent faces composed of congruent convex regular polygons. Euclid proved

that there are exactly five such solids: the

cube, dodecahedron, icosahedron, octahedron,

and tetrahedron.

Plato

2

related these geometrical shapes to classical elements.

The space limitations that reduce the number of regular three-dimensional solids to only five

are the following:

1. Each vertex of the solid must coincide with one vertex each of at least three faces.

2

History. (from wikipedia) The Platonic solids are named after Plato, who wrote about them in Timaeus. Plato

learned about these solids from his friend Theaetetus. Plato conceived the four classical elements as atoms with the

geometrical shapes of four of the five platonic solids that had been discovered by the Pythagoreans (in the Timaeus).

These are, of course, not the true shapes of atoms; but it turns out that they are some of the true shapes of packed

atoms and molecules, namely crystals: The mineral salt sodium chloride occurs in cubic crystals, fluorite (calcium

fluoride) in octahedra, and pyrite in dodecahedra.

This concept linked fire with the tetrahedron, earth with the cube, air with the octahedron and water with the

icosahedron. There was intuitive justification for these associations: the heat of fire feels sharp and stabbing (like

little tetrahedra). Air is made of the octahedron; its minuscule components are so smooth that one can barely feel

it. Water, the icosahedron, flows out of one’s hand when picked up, as if it is made of tiny little balls. By contrast,

a highly un-spherical solid, the hexahedron (cube) represents earth. These clumsy little solids cause dirt to crumble

and breaks when picked up, in stark difference to the smooth flow of water.

The fifth Platonic Solid, the dodecahedron, Plato obscurely remarks, ”...the god used for arranging the constellations

on the whole heaven” (Timaeus 55). He didn’t really know what else to do with it. Aristotle added a fifth element,

aithêr (aether in Latin, ”ether” in English) and postulated that the heavens were made of this element, but he had

no interest in matching it with Plato’s fifth solid.

Historically, Johannes Kepler followed the custom of the Renaissance in making mathematical correspondences,

and identified the five platonic solids with the five planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn which themselves

represented the five classical elements.

13

2. At each vertex of the solid, the total, among the adjacent faces, of the angles between

their respective adjacent sides must be less than 360.

3. The angles at all vertices of all faces of a Platonic solid are identical, so each vertex of

each face must contribute less than 360/3=120.

4. Regular polygons of six or more sides have only angles of 120 or more, so the common

face must be the triangle, square, or pentagon. And for:

- Triangular faces: each vertex of a regular triangle is 60, so a shape should be possible

with 3, 4, or 5 triangles meeting at a vertex; these are the tetrahedron, octahedron,

and icosahedron respectively.

- Square faces: each vertex of a square is 90, so there is only one arrangement possible

with three faces at a vertex, the cube.

- Pentagonal faces: each vertex is 108; again, only one arrangement, of three faces at a

vertex is possible, the dodecahedron.

The tetrahedral group Td is the group of symmetries of the tetrahedron. It has order 24 and

is isomorphic to the group S4 .

The icosahedral group Ih is the group of symmetries of the icosahedron and dodecahedron

having order 120, equivalent to the group direct product A5 × C2 (where A5 is the alternating group

and C2 is the cyclic group).

The octahedral group Oh is the group of symmetries of the octahedron and the cube. It is

isomorphic to S4 × C2 and has order 48.

There are many other classes of groups but we concentrated here to those that appear in chemistry

when considering groups of symmetries of molecules.

Finding a good classification for groups (i.e. finding classes that can describe various types of

groups well) and finding a good way to represent various abstract groups are two very difficult tasks

of the group theory. Group representation is a subfield of group theory that deals with these

issues.

Subgroups

A nonempty subset H of a group G is a subgroup if the elements of H form a group under the

operation from G restricted to H.

Every group has a subgroup consisting of identity element alone. This is called the trivial subgroup. The identity elements is an element of every subgroup of a group.

The entire group is a subgroup of itself. This is called the improper subgroup. The more

interesting examples are of nontrivial and proper subgroups.

Examples.

1. Set of even integers is a subgroup of all integers under addition.

2. Set of positive numbers is a subgroup of all real numbers different from 0 under multiplication.

3. Vectors co-linear with x-axis are a subgroup of all vectors in a real plane under addition.

14

4. Let determine

G1 1

1 1

tables a a

b b

c c

the subgroups

a b c

a b c

1 c b and

c 1 a

b a 1

of the two

G2 1 a

1 1 a

a a 1

b b c

c c b

non-isomorphic groups of order 4 G1 and G2 with the

b c

b c

c b .

a 1

1 a

left upper 2 × 2 part of the table for G1 , we see that it contains just the elements

1 a

1 a Note that this is a group for itself. So, this is a subgroup of G1 . The same

a 1

1 a b

· 1 b

· 1 c

1 1 a b

holds for 1 1 b

and

as the product of a

1 1 c An non-example is

a a 1 c

b b 1

c c 1

b b c 1

and b is c and c is not among the heading elements. So, the set {1, a, b} is not a subgroup of

G1 . Thus, the list of all the subgroups of G1 is: {1}, {1, a}, {1, b}, {1, c}, and G1 .

Consider the

·

1 and a. 1

a

Turning to G2 we can conclude that there is just one nontrivial and proper subgroup and this

is {1, a}. To prove this, suppose that there is a proper nontrivial subgroup H of G2 containing

b (similar proof works if you take c) instead of b. As bb = a, a must be in H as well. But ab = c,

so then c must be in H as well and so H = G2 so it is not proper.

In general, determining the number of subgroups of a given can be very difficult.3

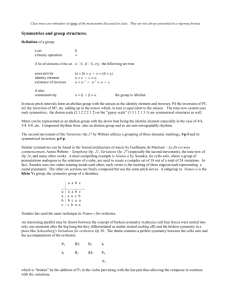

Symmetry (Point) Groups of Molecules

A point group is a group of symmetry operations which all leave at least one point unmoved.

These groups have the following operations as their basics elements. Note that if two operations are

in the group, then their composition is also an element of that group.

Element

Identity E

Symmetry plane σ (σh , σv , σd )

Inversion center i

Proper axis Cn

Improper axis Sn

Operation

not moving anything (i.e. rotation for 0 degrees)

Reflection with respect to a plane (horizontal, vertical, dihedral)

Reflection with respect to the origin

Rotation by 360/n degrees

Cn followed by σh

3

Another ”unsolvable” problem regarding groups is the so called word problem. The following two paragraphs

are taken from wikipedia.

The word problem for groups is the problem of deciding whether two given words of a presentation of a group

represent the same element. There exists no general algorithm for this problem, as was shown by Pyotr Sergeyevich

Novikov. The proof was announced in 1952 and published in 1955. A much simpler proof was obtained by Boone in

1959.

The word problem is only concerned with finitely presented groups, i.e. those groups which can be specified by

finitely many generators and finitely many relations among those generators. A word is a product of generators, and

two such words may denote the same element of the group even if they appear to be different, because by using the

group axioms and the given relations it may be possible to transform one word into the other. The problem then is

to find an algorithm which for any two given words decides whether they denote the same group element.

15

The set of all possible symmetries of each molecule constitutes a group. This set of operations

define the point group of the molecule.

There is a step-by-step algorithm that assigns a molecule to a point group (some of you may

cover it in a chemistry course). In this course, we will be interested both in understanding the

mathematical structure of point groups as well as the process of assigning one to a given molecule.

Type of point group

notation

cyclic

Cn

cyclic with horizontal planes

Cnh

cyclic with vertical planes

Cnv

non-axial

Ci , Cs

dihedral

Dn

dihedral with horizontal planes

Dnh

dihedral with planes between axes

Dnd

improper rotation

S2n

cubic groups

I, Ih , O, Oh , T, Th , Td

linear

C∞ , C∞v , C∞h , D∞ , D∞h

Word of caution: In chemistry, the same letter is used to denote both a group and an element

of a group. For example, a cyclic group of order n is denoted by Cn but the generating element is

also denoted by Cn . One should keep this is mind always when working with the point groups.

Chem.

Math.

Cn

Cn

Cnh

Cn × C2

Cnv

Dn

Ci , Cs

C2

Dn

Dn

Dnh

Cnv × C2 = Dn × C2

Dnd

D2n

S2n

C2n

I

A5

Ih

A 5 × C2

O

S4

Oh

S 4 × C2

T

A4

Th

A 4 × C2

Td

S4

C∞

C∞ = SO(2, R)

C∞v

D∞

C∞h

C ∞ × C2

D∞

D∞

D∞h

D∞ × C2

no. of el.

n

2n

2n

2

2n

4n

4n

2n

60

120

24

48

12

24

24

∞

∞

∞

∞

∞

presentation

ha|an = 1i

ha, b|an = b2 = 1, ba = abi

ha, b|an = b2 = 1, ba = an−1 bi

hb|b2 = 1i

n

ha, b|a = b2 = 1, ba = an−1 bi

see below

2n

ha, b|a = 1, b2 = 1, ba = a2n−1 bi

ha|a2n = 1i

ha, b|a2 = b3 = (ab)5 = 1i

ha, b, c|a2 = b3 = (ab)5 = 1, ac = ca, bc = cbi

ha, b|a2 = b3 = (ab)4 = 1i

2

ha, b, c|a = b3 = (ab)4 = 1, ac = ca, bc = cbi

ha, b|a2 = b3 = (ab)3 = 1i

ha, b, c|a2 = b3 = (ab)3 = 1, ac = ca, bc = cbi

ha, b|a2 = b3 = (ab)4 = 1i

no finite presentation

no finite presentation

no finite presentation

no finite presentation

no finite presentation

Note that some of these groups are isomorphic, so they do not have any differences significant for

mathematician, but are significantly different from a chemical point of view.

16

Let us concentrate first at the first eight groups in the above table. All of them are either dihedral,

cyclic, products of two cyclic or products of dihedral and cyclic groups. In the above representations,

the element a denotes the rotation and the element b a symmetry or, in the case of Ci , inversion i.

• If there is just one generator, the group is cyclic. This is the case for Cn , S2n , Cs and Ci .

• If there are two generators, a rotation a of order n or 2n and a symmetry b, the group will be

determined by the fact if the generators commute or not.

If they do, then we have a direct product of cyclic group generated with a and C2 , generated

with b. This will happen in the cases when b is the symmetry with respect to horizontal plane

because then it commutes with the rotation. Note that Cnh = Cn × C2 .

If a and b do not commute, we have Dn or D2n . This will happen if b is the symmetry with

respect to vertical plane because then ba = a−1 b. This is the case for Cnv , Dn and Dnd .

• If there are three generators: rotation a, symmetry with respect to a vertical plane b, and a

symmetry with respect to a horizontal plane c, these generators satisfy the relations

an = b2 = c2 = 1, ba = an−1 b, bc = cb, ac = ca

and these relations define the group Dn × C2 (Dnh in chemical notation).

In practice, not all values of n are possible. In crystallography, the feasible values of n are only

n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, due to the crystallographic restriction theorem. In its basic form, this theorem is

the observation that the rotational symmetries of a crystal are limited to 2-fold, 3-fold, 4-fold, and

6-fold. This is strictly true for the mathematical formalism, but in the physical world quasicrystals

occur with other symmetries, such as 5-fold. (find out more at wikipedia.org). So, there are just 32

crystallographic point groups.

• Let us turn our attention to point groups of linear molecules. Although none of these groups

have finite presentation, we can still describe them nicely enough. For example, group C∞

contains all the rotations around a fixed axis. So, we can identify it with the set of all possible

angles of rotations. As the rotation for 360 degrees is the same as rotation for 0 degrees, this

group is isomorphic to a group of all the angles represented on a unit circle. The angles are

added on an usual way. In mathematics, this group is known as SO(2, R). To follow notation

in chemistry, we denote it by C∞ .

If x is a rotation in C∞ and b the symmetry in C2 (so b2 = 1) then either bx = xb (in case b is

a symmetry with respect to a horizontal plane) or bx = x−1 b (if b is a symmetry with respect

to a vertical plane). If bx = xb, then we have a direct product C∞ × C2 = C∞h . If bx = x−1 b,

then we have an infinite version of Dn that is denoted by D∞ . Note that C∞v = D∞ .

If we have symmetry both with respect to vertical plane b and horizontal plane c, and x is any

rotation in C∞ , then we have the following relations

c2 = b2 = 1, bx = x−1 b, cx = xc.

These relations define the group D∞h = D∞ × C2 . This group is the infinite version of the

group Dnd .

17

Examples.

1. Water H2 O. This molecule has the following symmetries: identity E, rotation for 180 degrees

C2 , reflections with the respect to the vertical plane σv and their product C2 σv , (which is also

a reflection but with respect to a vertical plane perpendicular to the one used in σv ).

Using the second table, we can conclude that

this group is C2v . Writing down the Cayley table, we can see that this group is isomorphic

to C2 × C2 = ha, b|a2 = b2 = 1, ba = abi. In the

above presentation a corresponds to rotation

and b to one (any) of the symmetries.

2. Ethylene C2 H4 . If we place the molecule in the

coordinate system (lying in the xy-plane), then

the 3 reflections, with respect to xy, yz and xzplanes, are elements of the point group of this

molecule. The remaining elements of the point

group are:

rotations for 180 degrees with respect to all 3 axis (we can denote them by C2 (x), C2 (y) and

C2 (z)), inversion i and identity E. So, this group has 8 elements.

If we denote the reflections with a, b, and c, then the three rotations are ab, bc and abc.

Inversion is the remaining element ac. Together with identity, this corresponds to the 8 elements

previously described. So, we have 3 generators, all of order 2, giving us a group C2 × C2 × C2 =

C2v × C2 = D2 × C2 = D2h .

3. Boron trifluoride BF3 . There are two nontrivial rotations: a rotation for 120 and a2 rotation

for 240 degrees. There are symmetries

with respect to vertical plane b and horizontal plane c. As a and c commute and ba = a2 b, we

have D3 × C2 . Similarly as in previous example, this is Dnh -type and in this case n = 3. The

presentation of this group is

ha, b, c|a3 = 1, b2 = 1, c2 = 1, ca = ac, cb = bc, ba = a2 bi.

4. Bromine Pentafluoride BrF5 . Four fluor atoms

line in the same plane forming the vertices of a

square. Bromine atom is in the center of that

square and the remaining fluor atom is directly

above the bromine.

Because of that fifth fluor, there are no symmetries with respect to horizontal plane.

Recall that Dn is the group of symmetries of a regular n-tagon. So, the group of symmetries

of a square is D4 . We have two generators - rotation for 90 degrees a and the symmetry b with

18

respect to (any of the four) vertical planes: two with respect to vertical planes (xz and yz axes)

and two with respect to diagonals of the square. Thus, D4 has 8 elements: identity, 3 rotations

a, a2 and a3 and 4 symmetries b, ab, a2 b and a3 b.

So, the bromine pentafluoride molecules has the same symmetries as a square D4 = C4v .

5. CHFClBr. All 5 atoms are different so just the

trivial symmetry is present. Thus, the point

group is the trivial (one element) group.

6. HClBrC-CHClBr. There is just one nontrivial

operation - the inversion with respect to the

center. So, the group is Ci = C2 = hb|b2 = 1i.

7. Hydrogen chloride HCl. All the rotations for any angle between 0 and 2π with 0 and 2π

identified are the elements of the point group of this molecule. These rotations constitute the

group denoted C∞ = SO(2, R). There is also the

symmetry with respect to the vertical plane

b = σv (with respect to yz-plane if the molecule

stands ”upright”). Since b does not commute

with the rotations, we have C∞v = D∞ .

8. Hydrogen H2 . The hydrogen is a linear molecule with two identical atoms.

In addition to transformations from the previous example, the symmetry with respect to

horizontal plane c = σh is also present. Since

c commutes with a and b, the group is D∞h =

C∞v × C2 .

There are many resources on the web detailing step-by-step process for finding the point group for

any molecule and multimedia programs that helps you identify the point group of a given molecule.

Many websites also have more examples of point groups. Feel free to explore those resources.

Practice Problems.

1. (a) Prove that the set of real numbers different from − 13 is a group under the following operation

a ∗ b = a + b + 3ab.

(b) Determine whether it a group if − 31 is included in the set.

19

a b

2. Consider 2 × 2 matrices of the form

where a, b, c are real numbers with a 6= 0 and

0 c

c 6= 0. These matrices are called upper triangular invertible matrices. Show that the set of

such matrices with matrix multiplication is a group.

3. Since 5 is a prime number, there is just one abelian group of order 5. Prove that this is the only

(non-isomorphic) group of order 5. Hint: Create identity skeleton first. Show that the case

when all the elements are inverse to themselves is not possible – prove that the associativity

fails.

4. Write down the Cayley tables for the following groups.

(a) C2 × C3 , (b) C2 × C2 × C2 , (c) D5 .

5. Groups of order 8. The groups C8 , C4 × C2 and C2 × C2 × C2 , D4 have order 8. There is

another group of order 8, called the quaternion group, usually denoted by Q, that can be

presented by

ha, b|a4 = 1, a2 = b2 , ba = a3 bi.

(a) Write down the Cayley table for this group and compare. Compare the Cayley tables for

three groups of order 8 generated by two elements: C4 ×C2 = ha, b|a4 = 1, b2 = 1, ba = abi,

D4 = ha, b|a4 = 1, b2 = 1, ba = a3 bi, and Q = ha, b|a4 = 1, b2 = a2 , ba = a3 bi.

(b) Demonstrate that five groups of order 8, C8 , C4 × C2 and C2 × C2 × C2 , D4 and Q, are not

isomorphic to each other.

6. Produce all isomorphism classes of abelian groups of order 36.

7. Determine if the following pairs of groups are isomorphic. If they are, produce the isomorphism.

If they are not, explain why.

(a) C3 and D3 .

(b) C6 and D3 .

(c) S3 and D3 .

(d) Sn and Dn for n > 3.

8. Describe all the subgroups of

(a) D3 ,

(b) C6 = C3 × C2 .

9. Describe the point groups of the following molecules. Write down the presentations of the point

groups. Identify each group element as a symmetry operation.

(a) Ammonia NH3 ,

(b) Chloramine NH2 Cl

20

(c) Hydrogen cyanide HCN.

Solutions.

1. Let us check axioms A1–A4.

A1. If a and b are real numbers different from − 13 , it is clear that the product a ∗ b = a + b + 3ab

is a real number but you need to check it is different from − 13 . Let us examine conditions on

a and b that would make this product equal to − 31 .

1

1

1

a ∗ b = a + b + 3ab = − ⇒ a + b + 3ab + = 0 ⇒ a + + b(1 + 3a) = 0 ⇒

3

3

3

1

1

1

1

1

1

a + + 3b( + a) = 0 ⇒ (a + )(1 + 3b) = 0 ⇒ a + = 0 or 1 + 3b = 0 ⇒ a = − or b = − .

3

3

3

3

3

3

1

So, if a and b are real numbers different from − 3 , then the product a ∗ b is different from − 13

as well. Thus, the operation is closed.

A2. Check the associativity.

(a ∗ b) ∗ c =

=

=

=

a ∗ (b ∗ c) =

=

=

=

(a + b + 3ab) ∗ c

(a + b + 3ab) + c + 3(a + b + 3ab)c

a + b + 3ab + c + 3ac + 3bc + 9abc

a + b + c + 3ab + 3ac + 3bc + 9abc

a ∗ (b + c + 3bc)

a + (b + c + 3bc) + 3a(b + c + 3bc)

a + b + c + 3bc + 3ab + 3ac + 9abc

a + b + c + 3ab + 3ac + 3bc + 9abc

Thus, the axiom A2 holds.

A3. You are looking for a number x 6=

.

every a 6= −1

3

−1

3

with the property that a ∗ x = a and x ∗ a = a for

a ∗ x = a ⇒ a + x + 3ax = a ⇒ x + 3ax = 0 ⇒ x(1 + 3a) = 0

Since a 6= − 13 , 1 + 3a 6= 0 and we can cancel the equation x(1 + 3a) = 0 to get that x = 0.

Thus, a ∗ 0 = a.

Check that 0 ∗ a = 0 + a + 3(0)a = a as well. Thus, the group identity element is 0.

A4. For any a 6=

and x ∗ a = 0.

−1

,

3

you are looking for a number x 6=

−1

3

with the property that a ∗ x = 0

a ∗ x = 0 ⇒ a + x + 3ax = 0 ⇒ x + 3ax = −a ⇒ x(1 + 3a) = −a ⇒ x =

−a

1 + 3a

Note that we can divide by 1 + 3a since a 6= −1

. Check that x ∗ a = 0 as well. Indeed

3

−a+(1+3a)a−3a2

−a

−a

−a

−a+a+3a2 −3a2

0

∗ a = 1+3a + a + 3a 1+3a =

=

= 1+3a

= 0.

1+3a

1+3a

1+3a

If we considered all real numbers instead of all numbers different from −1

, we would not get a

3

−1

group since the axiom A4 would fail. Indeed, the equation 3 ∗ x = 0 has no solutions:

−1

−1

−1

−1

−1

∗x=0⇒

+ x + 3( )x = 0 ⇒

+x−x=0⇒

= 0.

3

3

3

3

3

Thus, the element

−1

3

does not have an inverse.

21

2. Check the four axioms.

A1. We need to show that the product of two upper triangular

invertible

matrices

is again an

a b

p q

upper triangular invertible matrix. Consider the matrices

and

with a, c, p, r

0 c

0 r

non-zero.

a b

0 c

p q

0 r

=

ap aq + br

0

cr

Thus, the product is again an upper triangular matrix. It is invertible since ap 6= 0 because

both a and p are non-zero, and cr 6= 0 because both c and r are non-zero.

A2.

a b

0 c

a b

0 c

p q

0 r

p q

0 r

u v

0 w

u v

0 w

=

=

u v

0 w

pu pv + qw

0

rw

ap aq + br

0

cr

a b

0 c

apu apv + (aq + br)w

0

crw

apu a(pv + qw) + brw

0

crw

=

=

The associativity holds since

apv + (aq + br)w = apv + aqw + brw

and

a(pv + qw) + brw = apv + aqw + brw.

x y

0 z

A3. You are looking for an invertible matrix X =

such that AX = A for any invertible

a b

matrix A =

.

0 c

a b

x y

a b

ax ay + bz

a b

AX = A ⇒

=

⇒

=

0 c

0 z

0 c

0

cz

0 c

This yields the equations ax = a, ay + bz = b and cz = c. Since a 6= 0 and c 6= 0, the first

and third equation give us x = 1 and z = 1. The second equation becomes ay + b = b ⇒ ay =

1 0

0 ⇒ y = 0 since a 6= 0. Thus we have that X =

, the identity matrix. The equation

0 1

XA = A holds in this case as well.

If you suspected

that the identity

matrix is the identity element, you could just check that

1 0

1 0

A

= A and

A = A.

0 1

0 1

1 0

a b

A4. Let I denote the identity matrix

. For any given invertible matrix A =

,

0 1 0

c

x y

you are looking for an invertible matrix X =

such that AX = I and XA = I.

0 z

22

AX = I ⇒

a b

0 c

x y

0 z

1 0

0 1

=

ax ay + bz

0

cz

⇒

=

1 0

0 1

This yields the equations ax = 1, ay + bz = 0 and cz = 1. Since a 6= 0 and c 6= 0, the first and

1

third equation give us x = a1 and z = 1c . The second

equation

becomes ay + b c = 0 ⇒ ay =

−b

c

⇒y=

−b

ac

1

a

since a 6= 0. Thus we have that X =

0

well.

−b

ac

1

c

. You can check that XA = I as

3. Following the hint, assume that the square of all four non-identity elements a, b, c, d is 1. In this

case, the product ab is either c or d. Assume it is c first. This implies the following Cayley’s

table that yields further relations described in the second table.

·

1

a

b

c

d

1 a b c d

1 a b c d

a 1 c

b

1

c

1

d

1

⇒

·

1

a

b

c

d

1 a b c d

1 a b c d

a 1 c d b

b

1

c

d 1

d

a

1

However, the associativity fails in this case since a(bb) = a · 1 = a and (ab)b = cb = d so

a(bb) 6= (ab)b. You arrive to the similar contradiction assuming that ab = d.

Thus, you have to have two pairs of mutually inverse elements. Assume that a is inverse to d

and b to c. The product aa can be b or c in this case. Assume it is b first. This creates the

following table and the isomorphism with C5 .

·

1

a

b

c

d

1

1

a

b

c

d

a b c d

a b c d

b

1

1

1

1

⇒

·

1

a

b

c

d

1

1

a

b

c

d

a

a

b

c

d

1

b

b

c

d

1

a

c

c

d

1

a

b

d

d

1

a

b

c

∼

=

· 1 a

1 1 a

a a a2

a2 a2 a3

a3 a3 a4

a4 a4 1

a2

a2

a3

a4

1

a

a3

a3

a4

1

a

a2

a4

a4

1

a

a2

a3

Assuming that aa = c also creates an isomorphism with C5 .

4. (a) The table for C2 × C3 can be found in the section on direct product of cyclic groups.

(b) C2 × C2 × C2 = ha, b, c|a2 = b2 = c2 = 1, ab = ba, ac = ca, bc = cbi. The Cayley table is also

displayed.

(c) D5 = ha, b|a5 = 1, b2 = 1, a4 b = bai. Thus, this group consists of 10 elements: 1, a, a2 , a3 ,

23

a4 , b, ab, a2 b, a3 b, a4 b.

1

a

b

c

ab ac bc abc

1

1

a

b

c

ab ac bc abc

a

a

1 ab ac

b

c abc bc

b

b

ab 1

bc

a abc c

ac

c

ac bc

1 abc a

b

ab

c

ab ab

b

a abc 1

bc ac

c

c abc a

bc

1 ab

b

ac ac

bc bc abc c

b

ac ab 1

a

abc abc bc ac ab

c

b

a

1

D5 1

a a2 a3 a4

b ab

2

3

4

1

1

a a

a

a

b ab

2

3

4

a

a a

a

a

1 ab a2 b

2

2

3

4

a

a

a

a

1

a a 2 b a3 b

a3 a3 a4

1

a a2 a3 b a4 b

4

4

a

1

a a2 a3 a4 b b

a

b

b a4 b a3 b a2 b ab 1 a4

1

ab ab b a4 b a3 b a2 b a

a2 b a2 b ab b a4 b a3 b a2 a

a3 b a3 b a2 b ab b a4 b a3 a2

a4 b a4 b a3 b a2 b ab b a4 a3

a2 b

a2 b

a3 b

a4 b

b

ab

a3

a4

1

a

a2

a3 b

a3 b

a4 b

b

ab

a2 b

a2

a3

a4

1

a

5. (a) The three Cayley tables for C4 × C2 , dihedral D4 and the quaternion group Q are below.

The first group differs from the latter two in the bottom half of the table. The differences

between D4 and Q are in the bottom right part of the table and they are highlighted in the

table for Q.

a a2 a3

b ab a2 b a3 b

C4 × C2 1

1

1

a a2 a3

b ab a2 b a3 b

2

3

a a

a

1 ab a2 b a3 b b

a

a2

a2 a3

1

a a2 b a3 b b ab

a3

a3

1

a a2 a3 b b ab a2 b

b ab a2 b a3 b 1

a a2 a3

b

ab

ab a2 b a3 b b

a a 2 a3

1

2

2

3

2

3

ab

a b a b b ab a

a

1

a

a3 b

a3 b b ab a2 b a3

1

a a2

a a2 a3

b ab a2 b a3 b

D4 1

1

1

a a2 a3

b ab a2 b a3 b

a a2 a3

1 ab a2 b a3 b b

a

2

2

3

a

a

a

1

a a2 b a3 b b ab

1

a a2 a3 b b ab a2 b

a3 a3

b

b a3 b a2 b ab 1 a3 a2 a

1 a3 a2

ab ab b a3 b a2 b a

a2 b a2 b ab b a3 b a2 a

1 a3

3

3

2

3

2

a b a b a b ab b a

a

a

1

1

a a2 a3

Q

1

1

a a2 a3

a a2 a3

1

a

2

a

a2 a3

1

a

1

a a2

a3 a3

b

b a3 b a2 b ab

ab ab b a3 b a2 b

a2 b a2 b ab b a3 b

a3 b a3 b a2 b ab b

b

b

ab

a2 b

a3 b

a2

a3

1

a

ab

ab

a2 b

a3 b

b

a

a2

a3

1

a2 b

a2 b

a3 b

b

ab

1

a

a2

a3

a3 b

a3 b

b

ab

a2 b

a3

1

a

a2

(b) Out of five groups of order 8, C8 , C4 × C2 and C2 × C2 × C2 , D4 and Q, the first three are

abelian and the last two are not so none of the three abelian groups is isomorphic with two

non-abelian groups. Furthermore, no abelian group is isomorphic to any other abelian group

because the order of elements do not match: C8 has an element (four of them in fact) of order 8,

the other two do not. C4 × C2 has an element (four of them in fact) of order 4 and C2 × C2 × C2

does not.

D4 and Q are not isomorphic because D4 has 5 elements of order 2 and just 2 of order 4 and

Q has 2 elements of order 2 and 5 elements of order 4.

24

a4 b

a4 b

b

ab

a2 b

a3 b

a

a2

a3

a4

1

6. Write 36 as product of powers of prime numbers: 36 = 4 · 9 = 22 · 32 . Since 2 and 3 are

relatively prime, the groups C3 × C3 and C9 can be combined with any of the groups C2 × C2 ,

or C4 creating isomorphic pairs of groups. C3 × C3 is not isomorphic to C9 and C2 × C2 is not

isomorphic to C4 . Thus, there are 4 non-isomorphic abelian groups of order 36

1.

2.

3.

4.

∼

= C6 × C3 × C2

∼

= C3 × C12

∼

= C18 × C2

∼

= C36

C3 × C3 × C2 × C2

C3 × C3 × C4

C9 × C2 × C2

C9 × C4

∼

= C6 × C6

7. (a) C3 and D3 are not isomorphic because one has 3 elements and the other has 6 elements.

(b) C6 and D3 are not isomorphic because one is abelian and the other is not.

(c) S3 and D3 are isomorphic.

Recall that S3 has 6 elements represented

by mappings that map (1, 2, 3) to (1, 2, 3),

(2, 3, 1), (3, 1, 2), (1, 3, 2), (3, 2, 1), and

(2, 1, 3). Let us denote these 6 mappings

by f1 to f6 . Compare that with symmetry

operations of an equilateral triangle.

The map f1 is the identity, f2 is rotation for 120 degrees, f3 is rotation for 240 degrees

and so f22 = f3 . Thus, the order of f2 is 3. The elements f4 , f5 and f6 are symmetries

with respect to three axes on the figure above. Thus, these elements are of order 2.

The product f2 f4 represents the composition of maps f2 and f4 that turns out to be the

mapping f2 f4 = (3, 2, 1) = f5 . Finally, the product f22 f4 = f2 f5 = f6 .

This demonstrates that there is one-to-one mapping of elements of S3 onto the elements

of D3 that preserves all the relations among the elements. More precisely, note that f2

and f4 generate the group. Let us denote f1 = 1, f2 = a and f4 = b. Then f3 = f22 = a2 ,

ab = f2 f4 = f5 and a2 b = f22 f4 = f6 . The relation for commuting the generators is

ba = f4 f2 = f6 = a2 b. Thus, S3 can be presented by

ha, b|a3 = 1, b2 = 1, ba = a2 bi

which is the presentation of D3 as well. So, the groups are isomorphic.

Writing Cayley tables for these two groups produces the same tables that are a match

further demonstrates the validity of this reasoning.

(d)

(e) Sn and Dn are not isomorphic for n > 3 because one has 2n and the other n! elements.

n! is larger than 2n for n > 3.

8. (a) Besides the identity, D3 has three elements of order 2 (b, ab, and a2 b) and two elements of

order 3 (a and a2 ). This determines the following.

25

number of subgroups

1

3

1

1

order of subgroup

1

2

3

6

subgroups

{1}

{1, b}, {1, ab}, {1, a2 b}

{1, a, a2 }

D3

total number = 6

This represents the complete list because adding any element to any one of the four nontrivial

subgroups, you will end up with the entire group D4 . For example, if you add a to {1, b}, then

the product a2 , ab and a2 b have to be in this subgroup in order for it to remain closed. If you

add ab to {1, b}, then the products abb = a and bab = a2 have to be in. But in this case a2 b

has to be in as well. So, you again arrive to all six elements present. Convince yourself that all

the other scenarios will result in the same conclusion: the list of the subgroups is complete.

(b) Besides the identity, C6 has two elements of order 6 (a, and a5 ), two elements order 3 (a2

and a4 ) and one element of order 2 (a3 ). This determines the following.

number of subgroups

1

1

1

1

order of subgroup

1

2

3

6

subgroups

{1}

{1, a3 }

{1, a2 , a4 }

C6

total number = 4

This represents the complete list because adding any element to any of the two nontrivial

subgroups, you will end up with the entire group C6 . For example, if you add a2 to {1, a3 },

then the product a2 a3 = a5 . Moreover, the inverse a4 of a2 has to be in too and so the product

a4 a3 = a has to be in too. Thus, you end up with all six elements. Similarly, adding a3 , for

example, to {1, a2 , a4 } forces the product a2 a3 = a5 and a3 a4 = a to be in the subgroup. So it

becomes entire C6 . Thus, the above four subgroups represent the complete list.

9. (a) Ammonia molecule has the same symmetries as the equilateral triangle. It has no symmetries with respect to the horizontal plane since this molecule is not planar. Thus, the

point group of NH3 , is the dihedral group D3 = C3v . It has presentation ha, b|a3 = 1, b2 =

and 4π

. The elements

1, ba = a2 bi. The elements a and a2 correspond to rotations by 2π

3

3

2

b, ab and a b correspond to symmetries with respect to 3 vertical axis of symmetries.

(b) Chloramine NH2 Cl. The molecule is not planar so the only non-identity group element

is a single symmetry of order 2. So, the point group has two elements and so it is

C2 = ha|a2 = 1i.

(c) Hydrogen cyanide HCN is a linear molecule. Thus all the rotations for any angle between

0 and 2π are in the point group. There is also symmetry b with respect to the vertical

plane (vertical if the molecule stands ”upright”). Since b does not commute with the

rotations, we obtain C∞v = D∞ .

26