Life and Works of Schubert CD 1

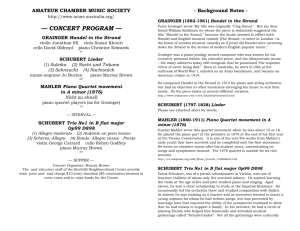

advertisement