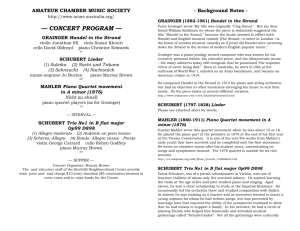

Program notes - Chamber Music Tulsa

advertisement

About the Program by Jason S. Heilman, Ph.D. Franz Schubert Quartet No. 12 in C Minor, D.703, Born January 31, 1797, in Lichtental, Vienna, Austria Died November 19, 1828, in Vienna “Quartet Movement” Composed in 1820; duration: 10 minutes By the early 1800s, the city of Vienna was renowned for its tradition of instrumental music, which followed in a line from Haydn to Mozart and finally to Beethoven. It was not a particularly good city to be a songwriter, however — even for a genius songwriter like Franz Schubert. Throughout the late 1810s and early 1820s, when Beethoven was redefining the symphony and the string quartet with each new work, Schubert was gaining underground fame for his innovative and expressive song settings of German romantic poetry. These Lieder, as they were called, were composed for home music-making, and in these private circles, Schubert was quickly becoming an in-demand celebrity. But Schubert knew that songs were a fleeting medium. Musical immortality in Vienna could only be gained through public performances of symphonies and string quartets. Unfortunately, this was the realm in which he struggled the most to gain any attention, though it was certainly not for lack of effort. Given that Franz Schubert did not live to see his thirtysecond birthday, it is not surprising that he left behind a large number of unfinished pieces. But on closer examination, it turns out that relatively few of these incomplete works date from his final year. Indeed, it seems that Schubert developed a habit of setting works aside and never returning, bouncing quickly as he did from one musical idea to another. The classic example is his Eighth Symphony, the famous “Unfinished Symphony,” for which Schubert completed only two movements. But that piece dates from 1822, some six years before his death; Schubert still managed to finish his Ninth Symphony and even start a Tenth in the years that followed. By the time he was 19 years old, Schubert had composed an astonishing 11 string quartets, plus numerous fragmentary pieces. The impetus for this prolific output was the composer’s own family: Schubert’s father, a Viennese schoolteacher, was an amateur cellist, and his two older brothers played violin. With Schubert on the viola, the family had a string quartet, and the precocious young composer soon began trying out his own musical ideas in this relatively friendly setting. These early quartets, which Schubert started composing at the age of 13, were mostly competent pieces, but hardly masterworks in the Mozartian mold. Many of them bear the stylistic hallmarks of Schubert’s music teacher, Mozart’s famous rival Antonio Salieri. When Schubert completed his schooling at age 17, life as a professional composer did not seem to be a likely prospect, so he reluctantly decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a schoolteacher. Yet he must have held out some hope that his fortunes might change, as he continued to compose prolifically in his spare time. Some of Schubert’s more sociable friends encouraged him to keep writing songs for their private gatherings, and this experience transformed the young composer. Schubert had already composed several popular Lieder by this time, including “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (“Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel,” 1814) and “Erlkönig” (“Erl-king,” 1815), but it was during the pivotal four-year span from 1816 to 1820 that he truly found his own voice. This voice can clearly be heard in such songs as “Der Wanderer” (“The Wanderer,” 1816), “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (“Death and the Maiden,” 1817), “Die Forelle” (“The Trout,” 1817), and “An die Musik” (“To Music,” 1817). Schubert also left behind several unfinished chamber works, the most notable of which is what would have been his Twelfth String Quartet. Started in December of 1820, this quartet was Schubert’s first attempt at the genre in nearly four years. During that time, Schubert’s musical style had matured considerably, as had his prospects: with a growing reputation from his Lieder, he now had the opportunity to write for professional chamber musicians for the first time. But this newfound freedom must have felt daunting, because Schubert only completed the first movement and 41 bars of the second before setting this quartet aside forever. It remained in obscurity until 1867 — nearly forty years after the composer’s death — when a wave of interest in all things Schubert swept Vienna. By then, the movement was regarded as a satisfying quartet in its own right and received its public premiere. This brief Quartettsatz (“quartet movement”) already shows many of the hallmarks of Schubert’s mature style in its grander scale and flowing melodicism. Set in sonata form, it opens with a nervous, scherzo-like first theme that is soon contrasted by a soaring, lyrical second. The themes are developed dramatically and return to end the movement with the same nervous energy as it began, leaving us to ponder what wonders we might have encountered if Schubert had completed the work. Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D.810, “Death and the Maiden” Composed in 1824; duration: 38 minutes Three years after setting his Twelfth Quartet aside, Schubert came face to face with his own mortality. In 1823, he spent several days in the hospital, suffering from a significant outbreak of the illness that would claim his life five years later. We are not sure what this illness was; traditionally it was thought to have been typhus or typhoid fever, but more recent biographers believe Schubert may have died of syphilis. Upon leaving the hospital, Schubert entered into what would be the last phase of his compositional life. Armed with a new burst of confidence, his works from that point on show even greater ambition in form and scale. In 1824, Schubert returned to the string quartet genre, composing two new pieces, both of which refer to earlier works in the composer’s already-vast output. Schubert’s Thirteenth String Quartet borrows a theme from his incidental music for the play Rosamunde, Princess of Cyprus, which he had only recently completed. His Fourteenth String Quartet uses a theme from the Lied “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (“Death and the Maiden”), which Schubert had composed some seven years prior during the pivotal phase in his musical development. Given how infrequently Schubert had quoted himself in his previous compositions (the famous “Trout” Quintet is another rare example), the reuse of these melodies seems significant — particularly in light of the composer’s recent brush with mortality. Schubert’s 1817 song “Death and the Maiden” is a setting of a German romantic poem by Matthias Claudius, who wrote under the pen name “Asmus.” The poem is an invented folk legend in which a young woman is visited by the figure of Death. Immediately, she pleads breathlessly for her life: Pass! Oh, pass! Go, vicious skeleton! I am still young! Go, please, And touch me not! But Death is insistent, calmly intoning: Give your hand, you beautiful and gentle thing. I am a friend, and come not to punish. Take heart! I am not vicious; You shall sleep softly in my arms. This song serves as the basis for a set of variations in the latter quartet’s second movement, but the overall tone of the struggle against Death seems to pervade the entire four-movement work. The piece opens with a bleak introduction, which forms the basis for the allegro movement’s vigorous first theme. This is soon contrasted by a more pastoral second theme, which begins unexpectedly in the relative major key before settling on the customary dominant, showing how far Schubert is starting to push the traditional sonata form. The andante con moto second movement presents the “Death and the Maiden” variations — though, interestingly, Schubert chose to use Death’s plaintive chorale and not the maiden’s pleading melody. This movement reaches dramatic heights, but its mood is quickly dispelled by the subsequent scherzo and trio, which may have been inspired by the well-known image of Death playing the violin. The presto fourth movement is a tarantella, a frantic Italian folk dance that was thought to ward off death from the bite of a tarantula. This brings the quartet from the grim specter of Death to a desperate affirmation of life. Unfortunately, the initial response to this quartet from Schubert’s circle was not positive, and he put it aside. This most famous of Schubert’s quartets was not rediscovered and published until 1831, nearly four years after the composer’s death. Program notes copyright © 2015 by Jason S. Heilman, Ph.D.