Laboratory Notes Psych 312:

Sensation Seeking and Alcohol Consumption

Research indicates that one of the major personality variables related to alcohol use is

sensation seeking (e.g., Cohen & Fromme, 2002; Zuckerman, 1994) in addition to other

factors such as gender, familial patterns, and family history of alcohol use (see review by

Roberti, 2004). Sensation seeking is a generalized preference for high or low levels of

sensory stimulation. People who are high in sensation seeking prefer a high level of

stimulation and are always looking for novel and exhilarating experiences. In contrast,

people who are low in sensation seeking prefer more modest levels of stimulation and

tend to choose tranquility over excitement (Weiten, 2004).

Sensation seeking was first described by Zuckerman (1971; 1974) as a personality trait

with a strong genetic predisposition (see the history of the identification of this personality

trait and the scale’s development in Zuckerman, Kolin, Price & Zoob, 1981). To determine

whether one is high, moderate, or low in sensation seeking, Zuckerman (1984) created a

Sensation Seeking Scale. Based on this scale, those high in sensation seeking (often

termed “sensation seekers”) display the following four sets of characteristics (Zuckerman,

1979; 1994): 1) Thrill and adventure seeking. They are more willing to engage in activities

that may involve a physical risk. Thus, they are more likely to go mountain climbing,

skydiving, surfing, and scuba diving; 2) Experience seeking . They are more willing to

volunteer for unusual experiments or activities that they may know little about. They tend to

relish extensive travel, provocative art, wild parties, and unusual friends; 3) Disinhibition.

They are relatively uninhibited. Hence they are prone to engaging in heavy drinking,

recreational drug use, gambling, and sexual experimentation; 4) Susceptibility to boredom.

They do not like monotony, have a low tolerance for routine and repetition, and they quickly

and easily become bored.

Interestingly, in terms of mental health, high sensation seekers are relatively tolerant of

stress; they find many types of potentially stressful events to be less threatening and

anxiety arousing than others (Franken, Gibson & Rowland, 1992). However, high

sensation seekers are more likely than others to exhibit impulsive, last-minute decision

making (Franken, 1993), poor health habits (Watanabe, 1998), reckless driving (Jonah,

1997) and high-risk sexual behavior (McCoul & Haslam, 2001). High sensation seeking is

also associated with problem drinking (Parent & Newman, 1999), recreational drug use and

gambling (Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000), delinquency (Luengo et al., 1994), and criminal

behavior (Arnett, 1996). For a recent review on behaviors and other personality traits

associated with high sensation seekers, see Roberti (2004). Also, see Martin Zuckerman’s

interview published in Psychology Today (Zuckerman, 2000) where he discusses behaviors

as well as biological characteristics associated with high sensation seeking.

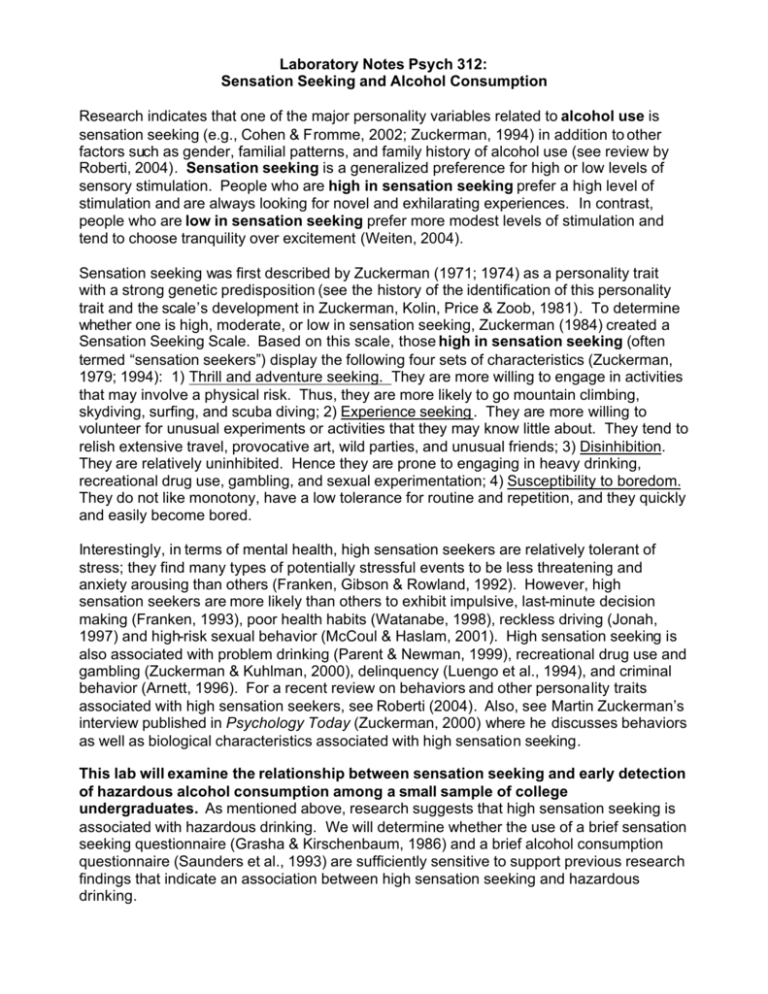

This lab will examine the relationship between sensation seeking and early detection

of hazardous alcohol consumption among a small sample of college

undergraduates. As mentioned above, research suggests that high sensation seeking is

associated with hazardous drinking. We will determine whether the use of a brief sensation

seeking questionnaire (Grasha & Kirschenbaum, 1986) and a brief alcohol consumption

questionnaire (Saunders et al., 1993) are sufficiently sensitive to support previous research

findings that indicate an association between high sensation seeking and hazardous

drinking.

Method:

Early detection of hazardous alcohol consumption will be assessed using the Alcohol

Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) developed by Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la

Fuente, and Grant (1993). This alcohol assessment was developed to detect problem

drinkers who may not yet be classified as alcoholics. It is a relatively short assessment that

was derived from a cross-national data set and hence appears to be culturally unbiased.

The actual questions contained in the AUDIT are presented in the Saunders et al. (1993)

appendix (pp. 803-804)

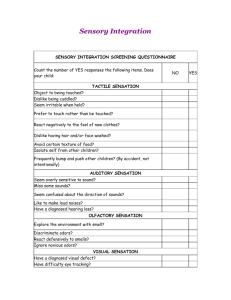

To obtain a rough estimate of whether one is high or moderate/low in sensation seeking, a

sensation seeking scale presented in Grasha and Kirschenbaum (1986) will be used.

This scale can be viewed by selecting “SS Scale” 1. Please note that this sensation

seeking scale provides only a rough approximation of one’s status on this personality trait.

Also, unlike the scale developed by Zuckerman (1984)2 , it does not provide separate

measures along the four characteristics of sensation seeking (thrill and adventure seeking,

experience seeking, disinhibition, and susceptibility to boredom). Instead, these separate

measures are combined. Results of this scale will be summarized as either 1) High

sensation seeking or 2) moderate/low sensation seeking in contrast to the typical way that

the scale is scored since we are only interested in identifying those who are high sensation

seekers and those who are not.

The scoring methods used for each scale are summarized at the bottom of each scale

Results:

A correlation will be used to analyze whether an increase in sensation seeking is positively

correlated with an increase in sensation seeking. Note: Although the cutoff scores for the

Audit and Sensation Seeking Scale are typically used for these scales (Audit = harmful

drinking: score of 8 or higher vs. non-harmful drinking: score of 7 or lower; Sensation

Seeking Scale = high sensation seeking: score of 11 or higher vs. moderate to low

sensation seeking: score of 10 or below), you will be conducting a correlation based on the

actual scores obtained from these two scales for each participant. The cutoff scores will

not be used, but you can use them to get an idea if you engage in harmful vs. non-harmful

drinking and whether you are high, moderate, or low in sensation seeking.

Footnotes:

1

For an example the Grasha and Kirschenbaum (1986) Sensation Seeking

Questionnaire used in this study see “SS Scale”; If you would like to determine

whether you are high, moderate, or low based on this scale, go to:

http://hksrch.com.hk/quiz/sen2.htm

2

For an example of the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality (Sensation Seeking)

Questionnaire typically used to assess sensation seeking go to:

http://www.rta.nsw.gov.au/licensing/tests/driverqualificationtest/sensationseekingscale/

References:

Cohen, E. S., & Fromme, K. (2002). Differential determinants of young adult substance use and

high-risk sexual behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(6), 1124-1150.

Franken, R. E. (1993). Sensation seeking and keeping your options open. Personality and Individual

Differences, 14(1), 247-249.

Franken, R. E., Gibson, K. J., & Rowland, G. L. (1992). Sensation seeking and the tendency to view

the world as threatening. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(1), 31-38.

Grasha, A. F., & Kirschenbaum, D. S. (1986). Adjustment and competence: Concepts and

application. Saint-Paul, MN: West.

Jonah, B. A. (1997). Sensation seeking and risky driving: A review and synthesis of the literature.

Accident Analysis and Prevention, 29 (5), 651-665.

Luengo, M. A., Otero, J. M., Carrillo-de- la-Pena, M. T., & Miron, L. (1994). Dimensions of

antisocial behavior in juvenile delinquency: A study of personality variables. Psychology,

Crime & Law, 1(1), 27-37.

McCoul, M. D., & Haslam, N. (2001). Predicting high risk sexual behavior in heterosexual and

homosexual men: The roles of impulsivity and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual

Differences, 31(8), 1303-1310.

Parent, E. C., & Newman, D. L. (1999). The role of sensation-seeking in alcohol use and risk-taking

behavior among college women. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 44(2), 12-28.

Roberti, J. W. (2004). A review of behavioral and biological correlates of sensation seeking. Journal

of Research in Personality, 38(3), 256-279.

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development

of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early

detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction, 88(6), 791-804.

Saunders, J. B., Baily, S., Phillips, M., & Allsop, S. (1993). Women with alcohol problems: Do they

relapse for reasons different to their male counterparts? Addiction, 88(10), 1413-1422.

Watanabe, M. (1998). The relationship between sensation seeking and health risk behavior: A survey

on traffic-related risk behavior, cigarette smoking and alcoho l drinking among university

students. Japanese Journal of Health Psychology, 11(1), 28-38.

Weiten, W. (2004). Psychology: Themes and variations. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Zuckerman, M. (1971). Dimensions of sensation seeking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 36(1), 45-52.

Zuckerman, M. (1979). Sensation seeking. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Zuckerman, M. (1984). Sensation seeking: A comparative approach to a human trait. Behavioral and

Brain Sciences, 7(3), 413-471.

Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York,

NY: Cambridge University Press.

Zuckerman, M. (2000). Are you a risk taker? Psychology Today, 33, 52-57.

Zuckerman, M., Kolin, E. A., Price, L., & Zoob, I. (1964). Development of a sensation-seeking

scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 28, 477-482.

Zuckerman, M., & Kuhlman, D. M. (2000). Personality and risk-taking: Common biosocial factors.

Journal of Personality, 68(6), 999-1029.

Zuckerman, M., Murtaugh, T., & Siegel, J. (1974). Sensation seeking and cortical augmentingreducing. Psychophysiology, 11(5), 535-542.