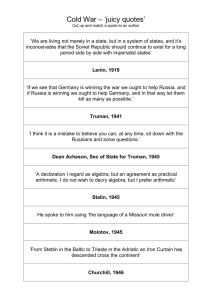

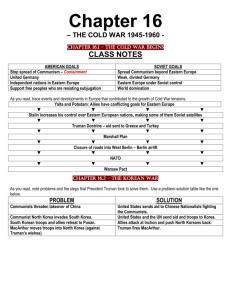

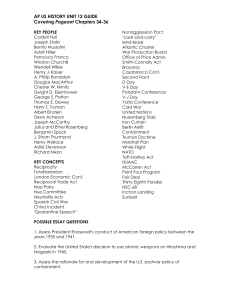

origins of the cold war

advertisement